Preventing Government Facial Recognition Oppression

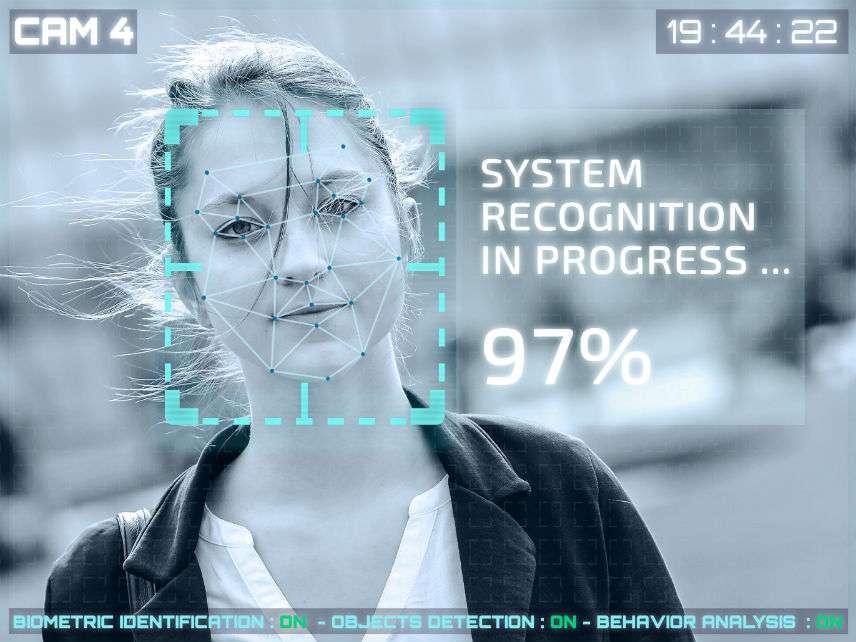

Pervasive real-time police surveillance is not just theoretical anymore.

"Facial recognition is the perfect tool for oppression," write Woodrow Hartzog, a professor of law and computer science at Northeastern University, and Evan Selinger, a philosopher at the Rochester Institute of Technology. It is, they persuasively argue, "the most uniquely dangerous surveillance mechanism ever invented."

During a speech at the Brookings Institution last December, Microsoft chief Brad Smith said, "If we fail to think these things through, we run the risk that we're going to suddenly find ourselves in the year 2024 and our lives are going to look a little too much like they came out of the book 1984." San Francisco's board of supervisors is considering an outright ban on police use of the technology.

The public is already uneasy about the widespread police use of facial recognition technology. A 2018 Brookings poll found that 50 percent of Americans "believe there should be limits on the use of facial recognition software by law enforcement, 26 percent do not, and 24 percent are unsure." Forty-two percent think that facial recognition software invades personal privacy, 28 percent do not, and 30 percent are unsure. Forty-nine percent believe the government should not compile a data base of people's faces, 22 percent think they should, and 29 percent are unsure.

The Project On Government Oversight (POGO), a nonpartisan watchdog, has just issued a report called Facing the Future of Surveillance. It starkly outlines the dangers to liberty posed by this technology, and it offers some recommendations for how to limit abuses.

Facial recognition technology combines the software for creating faceprints with vast photo databases and a pervasive deployment of surveillance cameras. The report notes that law enforcement can use facial recognition technology for four purposes: arrest identification (to confirm an arrestee's ID), field identification (to ID a person stopped by an officer), investigative identification (to obtain images for IDing an unidentified suspect), and real-time surveillance (to match unidentified folks to a watchlist).

Roughly half of all American adults already have pre-identified photos in databases that are used for law enforcement facial recognition searches. (As a user of Known Traveler and CLEAR, I am definitely among them.) Closed-circuit television (CCTV) cameras operated by police agencies are proliferating, as are police body cameras. The biggest worry is that the government could weave together the feeds from 30 million private security cameras to build a CCTV network on the scale similar to China's surveillance system.

Also, the authorities can scrape all those photos you've uploaded onto social media platforms to augment their image databases.

The POGO report highlights the fact that current facial recognition technologies have huge false positive rates and thus would mostly draw law enforcement attention to innocent citizens, even if they boost the "efficiency" of police surveillance. But the threats to civil liberties are heightened if we assume that facial recogniton technology is nearly perfect.

The report notes the Fourth Amendment's protection from "unreasonable searches and seizures" is meant to check the government's power over its citizens by limiting the amount of information it knows about us. Consider the 2011 Supreme Court decision in United States v. Jones, in which police tracked a suspect after surreptitiously attaching a GPS monitor to his vehicle. In her concurring opinion, Justice Sonia Sotomayor warned that unrestricted use of such relativey inexpensive technologies, which offer "such a substantial quantum of intimate information about any person whom the Government, in its unfettered discretion, chooses to track," could "alter the relationship between citizen and government in a way that is inimical to democratic society." She added, "Awareness that the Government may be watching chills associational and expressive freedoms."

The ways in which government could use unchecked facial recognition to oppress citizens are myriad, but let's just reflect on one example. In 1958, the State of Alabama demanded that the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) hand over its membership lists. In NAACP v. Alabama, the Supreme Court ruled against the state: "Immunity from state scrutiny of petitioner's membership lists is here so related to the right of petitioner's members to pursue their lawful private interests privately and to associate freely with others in doing so as to come within the protection of the Fourteenth Amendment." As the POGO report notes, the police could now, without consent or notification, obtain something like a group's membership list by simply deploying a camera outside one of its events and scanning the images through facial recognition software.

"If individuals believe that each camera on the street is cataloging every aspect of their daily lives, they may begin to alter their activities to hide from potential surveillance," notes the report. "That is something we must avoid, and we can do so through sensible reforms which demonstrate that checks against abuse are in place."

The report recommends that the government must obtain a probable-cause warrant whenever it seeks to use facial recognition to identify an individual. Using facial recognition for field identification must be limited to situations in which an officer has stopped someone based on probable cause that the individual has committed, is committing, or is about to commit a crime. Exigent circumstances such as IDing a missing person are excepted.

The report also recommends that the government should not be permitted to regularly scan locations and events, tag every individual without identifying them by name, save and update these profiles, and then use this stockpile of data to match a recorded profile once an individual becomes a person of interest. Creation of mass databases of these "metadata profiles" would severely undermine privacy and would risk chilling public participation in sensitive activities.

As Edward Snowden revealed, the National Security Agency was doing precisely this sort of database construction with respect to our personal electronic communications—an unconstitutional invasion of our privacy that turned out to be entirely useless when it came to preventing terrorist attacks. Domestic facial recognition surveillance would be considerably more intrusive.

The report also recommends that real-time facial recognition surveillance be strictly limited to emergency situations in which senior law enforcement officials must sign written authorizations declaring that specific individuals pose an immediate threat to public safety. In addition, facial recognition should be limited to preventing, investigating, and prosecuting only serious crimes—homicide, rape, robbery, aggravated assault, burglary, larceny, arson. In other words, police shouldn't be able to scan everyone at a football game with the aim of identifying suspects who also happen to be sports fans.

POGO also strongly recommends an indefinite moratorium on incorporating real-time facial recognition systems into police body cameras. Why? "Facial recognition built into body cameras would create the serious risk of isolating officers, forcing them to make unilateral decisions prompted by an unreliable computer system," the report observes. "Given the heightened possibility of misidentifications by real-time facial recognition, this would put the public at greater risk of misidentifications, and lead officers to make incorrect decisions that reduce law enforcement efficiency and harm police-community relations." Police body cameras should be used solely to monitor police interactions with the public.

In addition, all facial recognition systems must be tested by independent entities, and all law enforcement uses of facial recognition must be disclosed to criminal defendants prior to trial.

Adopting these recommendations would help ameliorate the threat posed by police use of facial recognition technology. But given the steady erosion of Fourth Amendment protections, reining in the government's abuse of this technology over the long term seems dicey.

Importantly, the POGO report argues that the principles of federalism should be followed too, so states and localities can enact stronger protections that are not preempted. I applaud the measure introduced at the San Francisco board of supervisors aiming to ban the police use of facial recognition technology in that city, and I hope that many more states and muncipalities will soon enact similar prohibitions.

Show Comments (52)