Trump Says Pain Pills Are 'So Highly Addictive.' He's Wrong.

The president wants to sue pharmaceutical companies for telling the truth about the addictive potential of their products.

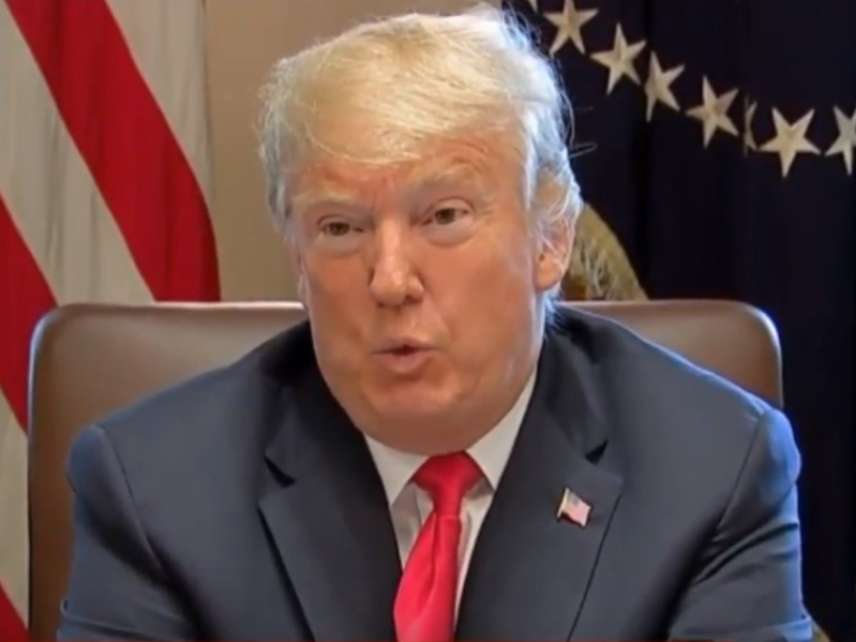

Donald Trump wants Attorney General Jeff Sessions to sue companies that make prescription pain medication because they "are really sending opioids at a level that it shouldn't be happening." Here is how the president summarized the issue at a Cabinet meeting yesterday:

It's so highly addictive. People go into a hospital with a broken arm; they come out, they're a drug addict. They get the arm fixed, but they're now a drug addict.

The implication—that people with fractured bones should not receive prescription analgesics, lest they become addicted—is rather alarming. But it is consistent with Sessions' view that patients suffering from severe pain should "take some aspirin" and "tough it out." So here is an issue where the president and his attorney general, long at odds over the latter's decision to recuse himself from the Russia investigation, see eye to eye. Trump and Sessions agree that opioids are "so highly addictive" that they should be avoided, even when they provide better pain relief than the alternatives.

Wall Street Journal reporter Rebecca Ballhaus seems sympathetic to this view. Reporting on Trump's litigation plans, she says the president is trying to "combat the highly addictive painkillers linked to tens of thousands of U.S. deaths a year." There are at least two problems with that statement: Pain pills are not "highly addictive," and they are not "linked to tens of thousands of U.S. deaths a year."

Let's take the second claim first, since it is refuted by the same data Ballhaus cites to demonstrate the magnitude of the problem that the lawsuit contemplated by Trump supposedly would address. "U.S. overdose deaths from all drugs," she says, "soared to more than 72,000 in 2017, a record, according to preliminary data released this week by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention." How many of those deaths involved pain pills? About 15,000, according to the CDC. Is that "tens of thousands"? No, it is not. Furthermore, many of those deaths also involved other drugs, including illicit opioids such as heroin and fentanyl, so it's misleading to blame them all on prescription analgesics.

Nor does the evidence support the assertion that pain pills are "highly addictive." A BMJ study published in January looked at "diagnostic code[s] for opioid dependence, abuse, or overdose" in the records of 568,612 patients who received narcotics after surgery between 2008 and 2016. The researchers found such evidence of "opioid misuse" in 5,906 cases, or 1 percent of the total. A JAMA study published last week looked at 56,686 patients between the ages of 13 and 30 who filled opioid prescriptions after they had their wisdom teeth extracted. The researchers found that 737, or 1.3 percent, were still getting opioids from pharmacies after three days, by which time the pain from the oral surgery should have subsided. According to the 2016 National Survey on Drug Use and Health, about 2 percent of the people who used prescription opioids that year, whether legally or illegally, experienced a "substance use disorder."

No doubt these studies missed some cases of addiction. Then again, their outcome measures—"opioid misuse," "persistent opioid use," and "substance use disorder," respectively—are not synonymous with addiction. A lot of the people who fell into those categories would bear little resemblance to the addicts portrayed in the government's anti-opioid ads, who are so desperate for more pain pills that they deliberately injure themselves. On the whole, the evidence indicates that addiction is a rare outcome among patients treated for acute pain, such as the guy with a broken arm in Trump's scenario.

The risk of addiction is obviously relevant to the choices made by doctors and patients, and it figures prominently in the lawsuits that a bunch of states have filed against opioid manufacturers, which Trump wants the Justice Department to imitiate. As Ballhaus notes, "The suits generally claim the companies misrepresented the addictive risk of their medicines in marketing materials."

That charge may be true on certain points, such as as the addictive potential of timed-release opioids that supposedly helped prevent nonmedical use but could easily be crushed for snorting or injection. But to the extent that pharmaceutical companies stated or implied that the risk of addiction among patients who take opioids for pain is low, they were telling the truth. It would not have been accurate for them to warn doctors that pain pills are "highly addictive." On that point, it's the government that is guilty of fraud.

Show Comments (84)