Holder Says Drug Offenders Are Serving 'Draconian' Sentences; Why Won't Obama Let Them Out?

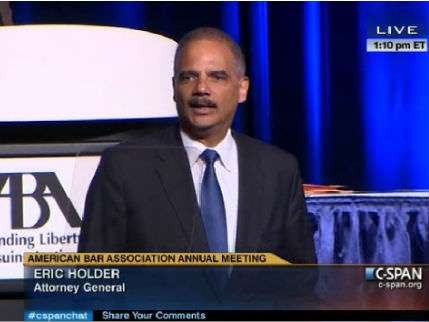

Attorney General Eric Holder's "Smart on Crime" initiative, which he unveiled today during a speech to the American Bar Association, includes several points that will please those of us who believe our criminal justice system is too big, too harsh, and too indiscriminate, starting with Holder's acknowledgement that our criminal justice system is too big, too harsh, and too indiscriminate:

With an outsized, unnecessarily large prison population, we need to ensure that incarceration is used to punish, deter, and rehabilitate—not merely to warehouse and forget….

Too many Americans go to too many prisons for far too long, and for no truly good law enforcement reason….

Widespread incarceration at the federal, state, and local levels is both ineffective and unsustainable. It imposes a significant economic burden—totaling $80 billion in 2010 alone—and it comes with human and moral costs that are impossible to calculate….

While the entire U.S. population has increased by about a third since 1980, the federal prison population has grown at an astonishing rate—by almost 800 percent.

Even though this country comprises just 5 percent of the world's population, we incarcerate almost a quarter of the world's prisoners….Roughly 40 percent of former federal prisoners—and more than 60 percent of former state prisoners—are rearrested or have their supervision revoked within three years after their release, at great cost to American taxpayers and often for technical or minor violations of the terms of their release.

Some statutes that mandate inflexible sentences—regardless of the individual conduct at issue in a particular case—reduce the discretion available to prosecutors, judges, and juries. Because they oftentimes generate unfairly long sentences, they breed disrespect for the system. When applied indiscriminately, they do not serve public safety. They—and some of the enforcement priorities we have set—have had a destabilizing effect on particular communities, largely poor and of color.

These are welcome words, especially since Holder repeatedly notes the role of "the so-called war on drugs" in the trends he decries. The solutions he proposes include sentencing reform along the lines of legislation co-sponsored by Sens. Dick Durbin (D-Ill.), Patrick Leahy (D-Vt.), Mike Lee (R-Utah), and Rand Paul (R-Ky.) that would give judges more discretion to depart from mandatory minimums in cases involving low-level, nonviolent drug offenders. Holder also has instructed federal prosecutors to use their existing discretion in two ways that could make criminal penalties less unjust:

Federal prosecutors cannot—and should not—bring every case or charge every defendant who stands accused of violating federal law….

I have today mandated a modification of the Justice Department's charging policies so that certain low-level, nonviolent drug offenders who have no ties to large-scale organizations, gangs, or cartels will no longer be charged with offenses that impose draconian mandatory minimum sentences. They now will be charged with offenses for which the accompanying sentences are better suited to their individual conduct, rather than excessive prison terms more appropriate for violent criminals or drug kingpins.

Since mandatory minimums are triggered by drug weight, the latter reform entails charging people with offenses involving unspecified amounts of controlled substances. While that change would reduce their prison terms, I'm not sure why it's necessary if U.S. attorneys follow Holder's suggestion that they refrain from prosecuting low-level offenders who don't belong in federal court. The practical impact of this change will depend on details such as what Holder means by "no ties to large-scale organizations, gangs, or cartels." Many marijuana dealers and pretty much all cocaine and heroin dealers arguably would fail that test. According to a memo that Holder sent to U.S. attorneys today, another requirement is "no significant criminal history." The memo adds that "a significant criminal history will normally be evidenced by three or more criminal history points but may involve fewer or greater depending on the nature of any prior convictions." In practice, a "significant" criminal history can be quite minor: An offense for which a defendant received a 60-day sentence, for instance, counts as two points, so a New Yorker who is caught with more than seven rounds in his gun after getting busted for "public display" of marijuana may be ineligible for Holder's mercy.

This initiative reminds me of the Fair Sentencing Act, which President Obama signed in 2010. Instead of eliminating the senseless sentencing disparity between smoked and snorted cocaine, the law reduced it, which surely was better than nothing but not quite as good as one might reasonably have expected given the bipartisan consensus that crack penalties were out of whack. (The law passed Congress almost unanimously.) Holder cites the Fair Sentencing Act as evidence that his boss has "felt strongly" about criminal justice reform "ever since his days as a community organizer on the South Side of Chicago." The other example of Obama's strong feelings that Holder mentions—"legislation that addressed racial profiling"—dates from Obama's days as a state legislator. As a U.S. senator and president, he has resembled a standard-issue drug warrior much more than a reformer. Most shamefully, he has failed to use his unilateral clemency powers to free the federal drug offenders whose prison terms he admits are unjust.

As Holder notes, his Smart on Crime initiative, like the Fair Sentencing Act, reflects a conclusion that has "attracted overwhelming, bipartisan support in 'red states' as well as 'blue states' ": The mindlessly harsh penalties produced by a reflexive tough-on-crime attitude are neither fair nor prudent. Or as UCLA criminologist Mark Kleiman puts it, "long prison terms are wasteful government spending." The attorney general's speech is encouraging as yet another sign of that realization. Whether it amounts to more remains to be seen.

Show Comments (39)