Citizens and the State: The Problem Is Bigger Than You Think

The NSA scandal is the tip of the iceberg.

"This abuse of state power," writes Chinese artist and dissident Ai Weiwei about the U.S. government's surveillance of U.S. citizens, "goes totally against my understanding of what it means to be a civilized society."

Weiwei has a better understanding of important things than Americans who find nothing wrong with the NSA's domestic spying. According to last week's polls, those Americans are in the majority. If you have done nothing wrong, many say, then you have nothing to hide. Really? We are supposed to believe the federal government does no wrong. If so, then by this logic we should declassify everything.

(There is some cold comfort in the poll, which shows that Democrats and Republicans support surveillance less when the other party holds the Oval Office. So some support for the NSA's activities may have more to to with team-sports loyalty than deep-rooted conviction.)

The revelations about the extent of domestic surveillance have been a big story since they broke earlier this month. And the story keeps getting bigger: MSN reports that the IRS is "acquiring a huge volume of personal information on taxpayers' digital activities, from eBay auctions to Facebook posts and, for the first time ever, credit card and e-payment transaction records." Soon it will have your health-insurance information, too.

Yet the tight focus on electronic surveillance keeps the bigger story out of the frame.

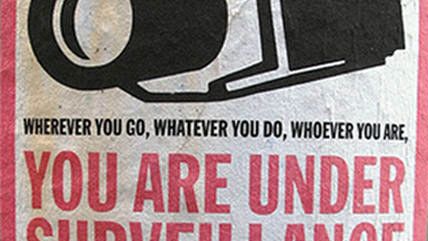

The bigger story concerns the increasingly asymmetric relationship between citizens and the state. The formerly secret program of domestic spying neatly illuminates one aspect of that asymmetry: The government knows, or can know, an awful lot about you. But you are not supposed to know even that it knows, let alone what it knows.

More of what the government does is classified than ever before. If you do not know what the government is doing then, obviously, you have no say over its activities. This flies in the face of the Declaration of Independence, which states that governments derive "their just powers from the consent of the governed." How can you consent to something you know nothing of?

The principle animating democratic and republican government is accountability to the governed. Yet more and more government action lies beyond the citizens' reach. As law professor Jonthan Turley explained in a Washington Post piece that appeared before the surveillance leaks, "our carefully constructed system of checks and balances is being negated by the rise of a fourth branch of government, an administrative state of sprawling departments and agencies that govern with increasing autonomy and decreasing transparency." (Viz., the NSA.)

The "vast majority of laws," he continues, "are not passed by Congress but issued as regulations, crafted largely by thousands of unnamed, unreachable bureaucrats." In 2007, he writes, "Congress enacted 138 public laws, while federal agencies" '" there are now 69 of them '" "finalized 2,926 rules."

The administrative state is taking over not only the legislative function, but also the judicial: Turley reports that "a citizen is 10 times more likely to be tried by an agency than by an actual court." And such agency creep, as it might be called, does not stop at the federal-state boundary.

Last month the Minnesota Supreme Court deferred answering a basic question of constitutional rights: Can the government enter your home without probable cause? A city ordinance in Red Wing, Minn., allows building inspectors with administrative warrants to enter rental units even when both the landlord and the tenant object. And as the Arlington-based Institute for Justice points out, they "do not require the government to have any evidence that there is anything actually wrong with a residence."

If you were asked to name a country that routinely stockpiles its citizens' private communications, keeps it in the dark about that activity and many others, tries citizens in extra-judicial proceedings for violations of edicts not passed by any legislature, and permits government agents to enter private domiciles at whim, you might say: China. Or Cuba. Or Saudi Arabia.

America is none of those places, of course. Not even close. But it is not a happy thing to note that the fourth branch of government '" the administrative state against which Republican politicians rail '" is largely impervious to elections. And that despite the uproar over domestic surveillance, an activity the election of Barack Obama was supposed to curtail, the general consensus seems to hold that such monitoring will continue unabated. Politicians come and go; autonomous agencies and mass surveillance are here to stay. Elections still matter a great deal in the U.S., but they matter now less than they once did '" and less than they should.

Show Comments (27)