Pit Stop Policing Transforms Traffic Violations Into High-Stakes Drug Hunts

South Carolina's Operation Rolling Thunder targets cash and contraband but harasses guilty and innocent travelers alike.

This is part five of Operation Shakedown, a series about heavy-handed traffic enforcement tactics and property seizures in Spartanburg County, South Carolina. Click here to read part one.

When officers stopped a Greyhound bus for going 5 mph over the speed limit on Interstate 85 in Spartanburg County, South Carolina, they were not interested in traffic enforcement.

The real target was drugs and cash, which the police pursued with factory-like precision. NASCAR pit crews could learn something about speed and efficiency from these experts.

The Florence County deputy who pulled that bus over on October 5, 2022, advised the driver of his violation and ordered him to gather his documents and come to the front of the patrol vehicle. By this time, a K9 handler had already moved into position with a drug dog for an open-air sniff around the bus exterior.

When the expected "positive indication" came, additional officers began opening suitcases in the undercarriage. Soon they had located more than 5 pounds of cocaine in vacuum-sealed bags. Using this evidence as probable cause, the police entered the bus cabin and began searching carry-on bags.

No Consent Needed

Officers did not need consent at this point. All the passengers were now criminal suspects.

The prize came when deputies opened a black bag between the feet of a passenger from Eden, North Carolina. The carry-on was stuffed with $500,000 cash—the biggest haul by far during Operation Rolling Thunder, a law enforcement blitz from October 2–6, 2022.

Homeland Security agents were on the scene within minutes to seize the currency and begin civil forfeiture. The passenger sitting with the bag claimed not to be its owner, relinquishing his claim to the cash, and went away in handcuffs. DNA evidence later linked him to the cocaine.

The bus driver received a traffic warning, the innocent passengers repacked their luggage, and the bus resumed its journey from Raleigh to Atlanta. The entire incident from start to finish took less than one hour.

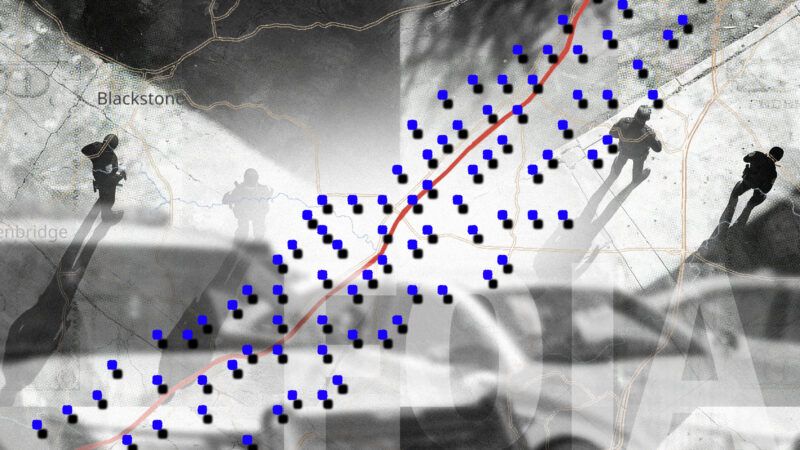

The agencies then reset the trap and waited for their next target. Over the course of five days, teams conducted an average of one search every 23 minutes from 10 a.m. to 9 p.m. Most of these intrusions were fruitless. Of 144 vehicle searches over five days, 102 turned up nothing at all, yet the officers kept trying.

Lather, rinse, repeat.

Robo-Enforcement

The automation is a problem. Courts allow individual pretextual traffic stops and systematic programs of roadside stops. But they do not allow the combination of these two things. Systemic programs like DUI checkpoints cannot be pretextual.

The Supreme Court recognized this boundary in the 2000 decision City of Indianapolis v. Edmond. In that case, law enforcement agencies established a system of roadside checkpoints. Some of the stops were legitimate: Officers would look for signs of impairment and also examine vehicles for safety issues. But the real purpose of the checkpoints was to search for drugs and, by extension, cash. The Supreme Court held that this violated the Fourth Amendment, which guarantees the right of the people to be "secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures."

As the court explained, even if such stops might be permissible to look for drunk drivers or other safety issues, "the checkpoint program unquestionably has the primary purpose of interdicting illegal narcotics."

Two of a Kind

Operation Rolling Thunder bears a striking resemblance to the Indianapolis checkpoint program. In both cases, law enforcement agencies operate an official program that involves pulling people over to search their vehicles. Law enforcement does this without any reasonable suspicion that a drug crime has occurred.

In both cases, the stops might be justified on other grounds—for traffic enforcement in Spartanburg County and to look for drunk drivers or other safety issues in Indianapolis. It is the programmatic purpose of searching for drugs and cash that makes the operations unconstitutional.

Put differently, pretextual stops are generally constitutional because courts hesitate to inquire into the subjective motivations of individual officers. But there is no need to look at the subjective motivation of any officer during Operation Rolling Thunder.

Spartanburg County Sheriff Chuck Wright has declared the purpose of the entire law enforcement blitz. He talks openly about using traffic laws to go after cash. "You charge somebody with a crime, and there's no reaction," he told reporters in 2019. "But you take their money, and you'll see a drug dealer cry."

On his campaign website, he has talked about forfeiture revenue filling the department's coffers. He says deputies receive "new equipment and technology such as mobile data terminals, cell phones and Tasers."

Wright does not mention the innocent people caught in Operation Rolling Thunder. This includes every passenger on the Atlanta-bound bus except one. Since the annual crackdowns began in 2006, the number of victims is likely in the thousands.

Operation Rolling Thunder is lucrative. But innocent I-85 travelers do not shed their constitutional rights when they enter Spartanburg County.

Show Comments (16)