If Congress Bans Abortion, This New Deal Precedent Will Be at the Center of the Legal Battles

A 1942 decision about the Commerce Clause takes on new importance post-Roe.

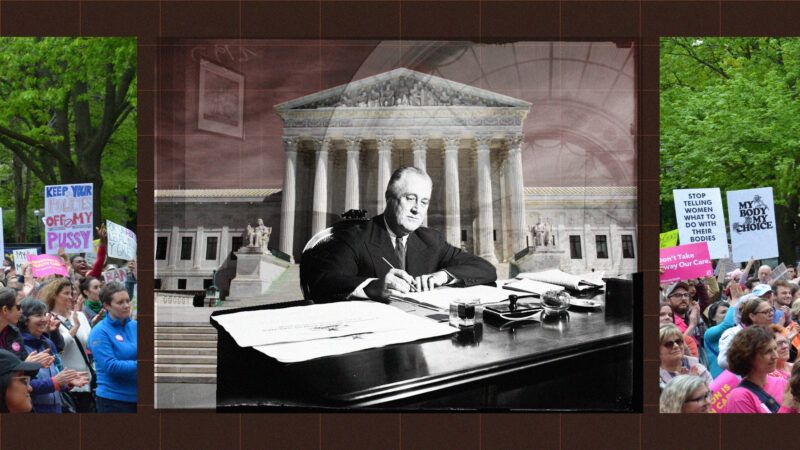

The U.S. Supreme Court's recent decision in Dobbs v. Jackson Women's Health Organization, which overturned Roe v. Wade (1973) and eliminated the constitutional right to abortion, has raised the possibility of a future Republican-controlled Congress seeking to ban abortion nationwide. If that happens, the resulting courtroom battles will likely center on a New Deal–era Supreme Court precedent that vastly expanded the scope of congressional power.

Under the Constitution, Congress possesses the authority "to regulate Commerce…among the several States." At the time of the founding, this power was understood to be a limited one. As Alexander Hamilton explained in Federalist 17, the Commerce Clause did not extend federal authority to "the supervision of agriculture and of other concerns of a similar nature, all those things, in short, which are proper to be provided for by local legislation." While Congress was permitted to regulate economic activity that crossed state lines, in other words, it was not empowered to control wholly intrastate economic undertakings.

That changed in the 1940s as a result of the federal government sanctioning an Ohio farmer named Roscoe Filburn for growing twice the amount of wheat that he was allowed to grow under the terms of the Agricultural Adjustment Act of 1938. Congress specifically invoked its power to regulate interstate commerce while enacting that New Deal law. The statute's goal was to raise agricultural prices by limiting the supply of crops hitting the national market.

Filburn fought the law by arguing that his extra wheat was not subject to federal regulation because it never once entered the stream of interstate commerce. In fact, he pointed out, his extra wheat never even left his own farm. It was used to either feed his livestock or make flour for his family's kitchen. It was nowhere near "Commerce…among the several States."

The Supreme Court thought otherwise and issued one of the most significant rulings of the New Deal era. Filburn's extra wheat may not have crossed state lines, the Court said in Wickard v. Filburn (1942), but entirely local activity of the sort was still subject to congressional regulation if it had a "substantial economic effect" on the national market. It was a huge political win for the agenda of President Franklin Roosevelt and a significant boost to Congress' overall regulatory authority.

Congressional power was boosted again by SCOTUS in the 2005 case of Gonzales v. Raich, which extended Wickard while upholding the federal ban on marijuana, even as applied to medical marijuana that was both legal to use under state law and which was cultivated and consumed entirely within the confines of a single state. Once again, the local conduct at issue was said to have a "substantial effect" on the interstate market.

Modern liberals have generally cheered for the broad vision of congressional power endorsed by Wickard and Raich. But they may feel somewhat differently about it when congressional Republicans invoke those same precedents in support of a federal abortion ban, which would also reach down to regulate wholly local activity. What is worse, plenty of Republicans in Congress seem willing to do just that.

The good news for abortion rights supporters is that any such use of Wickard and Raich may be rejected by even some of the most anti-abortion members of the current Supreme Court. Justice Clarence Thomas, for example, sharply dissented in Raich itself, faulting the majority opinion for turning the meaning of the Commerce Clause on its head. "By holding that Congress may regulate activity that is neither interstate nor commerce under the Interstate Commerce Clause," Thomas wrote, "the Court abandons any attempt to enforce the Constitution's limits on federal power." Thomas resumed his attack on the logic of Raich just last year.

Strange as it may sound, Thomas (and possibly a few other anti-abortion justices) might conceivably vote for the abortion rights side if a federal abortion ban ever reaches the Supreme Court.

Show Comments (218)