SCOTUS Again Upholds Double Prosecution and Punishment for the Same Crime

Unsatisfied by the outcome of one case, the feds secured a much more severe penalty the second time around.

The federal government prosecuted Merle Denezpi twice for the same crime. It also punished him twice: the first time with 140 days in a federal detention center, the second time with a prison sentence more than 70 times as long.

Although that may seem like an obvious violation of the Fifth Amendment's ban on double jeopardy, the Supreme Court last week ruled that it wasn't. As the six justices in the majority saw it, that puzzling conclusion was the logical result of the Court's counterintuitive precedents on this subject.

The Fifth Amendment says no person will "be subject for the same offence to be twice put in jeopardy of life or limb." But under the Court's longstanding "dual-sovereignty" doctrine, an offense is not "the same" when it is criminalized by two different governments.

That doctrine allows serial state and federal prosecutions for the same crime, opening the door to double punishment or a second trial after an acquittal. Although neither seems just, the Court says both are perfectly constitutional.

The justices reaffirmed that view in a 2019 case involving a man with a felony record who was convicted twice and punished twice for illegally possessing a gun—first in state court, then in federal court. Although the elements of the crime were the same in both cases, the majority said, the two prosecutions did not amount to double jeopardy because they involved two different "sovereigns."

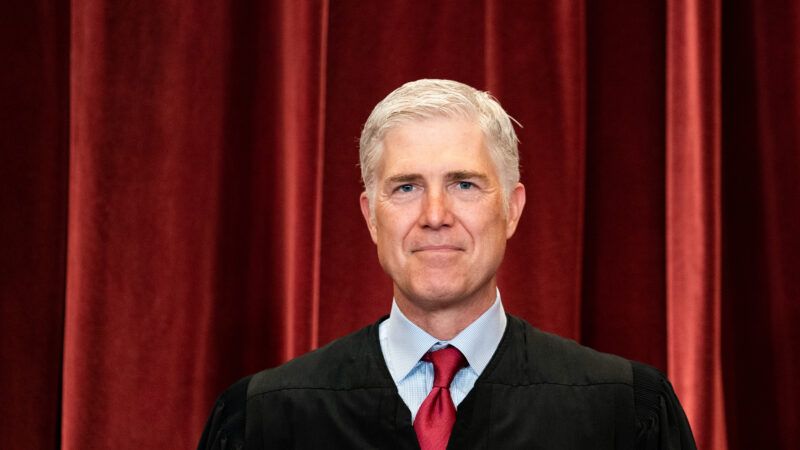

Justice Neil Gorsuch strenuously dissented in that case. "A free society does not allow its government to try the same individual for the same crime until it's happy with the result," he wrote. "Unfortunately, the Court today endorses a colossal exception to this ancient rule against double jeopardy."

Gorsuch, joined by Justices Sonia Sotomayor and Elena Kagan, dissented again last week. Even the "colossal exception" created by the dual-sovereignty doctrine, he said, is not big enough to encompass the two cases against Denezpi, both of which were pursued by the federal government under federal law.

In 2017, Denezpi and a woman identified as V.Y. in court papers, both members of the Navajo Nation, traveled to Towaoc, Colorado, a town within the Ute Mountain Ute Reservation where Denezpi's girlfriend lived. V.Y. alleged that Denezpi sexually assaulted her during the trip, while he maintained that the encounter was consensual.

After federal officials charged Denezpi with three crimes, he pleaded no contest to assault and battery, which is defined by tribal law but also punishable under the Code of Federal Regulations by up to six months in jail. A Court of Indian Offenses, part of a system established by the Department of the Interior, sentenced Denezpi to time served: 140 days.

Accepting V.Y.'s allegations as true, most people would view that penalty as excessively lenient, and federal prosecutors in Colorado evidently agreed. Six months after Denezpi completed his Interior Department sentence, the Justice Department charged him with aggravated sexual abuse, which resulted in a 30-year federal prison term.

"Mr. Denezpi's first crime of conviction (assault and battery) is a lesser included offense of his second crime of conviction (aggravated sexual abuse)," Gorsuch notes in his dissent. "And no one disputes that, under our precedents, that is normally enough to render them the 'same offense' and forbid a second prosecution."

Six justices nevertheless approved the second prosecution, tracing the authority for the first conviction to a distinct "sovereign": the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe. But as Gorsuch notes, the first prosecution was not based on tribal law per se; it was based on a federal regulation that criminalizes "violation of an approved tribal ordinance."

Although the two convictions involved the "same defendant," the "same crime," and the "same prosecuting authority," Gorsuch observes, the Court implausibly concluded that "the Double Jeopardy Clause has nothing to say about this case." Such reasoning amplifies the danger that Gorsuch decried in 2019, inviting the government to "try the same individual for the same crime until it's happy with the result."

© Copyright 2022 by Creators Syndicate Inc.

Show Comments (61)