When Kidnappings Were All the Rage

With panic in the air, federal law enforcement seized the moment.

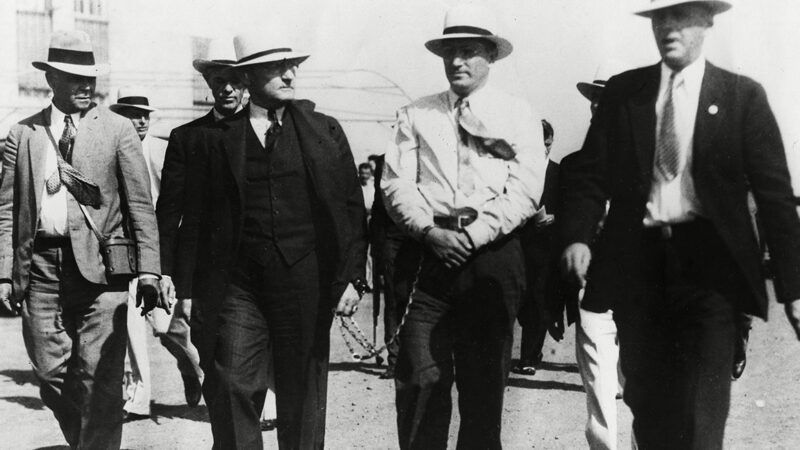

In the early 1930s, FBI chief J. Edgar Hoover placed advertisements in newspapers advising the families of kidnapping victims to contact his agency. The ads encouraged them to telegraph or phone, since a letter would take too long. Berenice Urschel kept the number by the phone, just in case. When her oil magnate husband was abducted at gunpoint in 1933, she called immediately.

Her husband, Charles F. Urschel, was taken from his Oklahoma City home to a farmhouse in Texas, where he was held until a $200,000 ransom was paid. That was how most high-profile kidnappings turned out: pay the money, get home safe. But the Urschel kidnapping was the first where the FBI was involved from start to finish, thanks to the new Federal Kidnapping Act—a.k.a. "the Lindbergh Law."

St. Louis police chief Joseph Gerk estimated that there had been 3,000 kidnapping cases nationally in 1931. This was a ballpark figure, based on a survey of law enforcement agencies and an assumption that a large proportion were never reported to police. But whatever the right number was, the crime was common enough to capture the public imagination. "The New York Times began publishing 'Recent Kidnappings in America' as a regular feature, while Time magazine reported kidnappings along with notable births, deaths, and other milestones," the attorney Carolyn Cox writes in The Snatch Racket. "Lloyd's of London began underwriting kidnap insurance in the United States for persons of 'unquestioned reputation' who passed thorough background checks designed to eliminate those considered at risk of faking their own kidnappings."

Anxious parents had their children fingerprinted by the FBI, just in case, and hired guards for their houses. At the same time, across the country, two banks a day were being robbed. Crime seemed to be out of control.

Before the Federal Kidnapping Act took effect in 1932, kidnapping itself had not been a federal crime; it became one only if the victim was transported across state lines (or if the ransomers posted their demands, subjecting them to mail fraud laws). Of course, it wasn't always clear if a victim had been taken across state lines until after the kidnapping was resolved. Hoover saw an opportunity to extend his agency's remit, and plenty of legislators were ready to help him. The turning point came with the 1932 abduction of Charles Lindbergh's baby son.

In 1927, Lindbergh had piloted the first solo flight across the Atlantic Ocean, making him arguably the most famous person in America. His child's disappearance was a national story, and it brought to the fore how kidnappings had been handled up to that point—informally, and usually with shady intermediaries. Lindbergh had followed the standard procedure for rich victims: He reached out however he could to underworld figures, asking for help.

As Cox explains, the kidnapping business operated in a murky world of police corruption and old-school machine politics. Local police departments were often up to their elbows in local gangster activity, and vice versa. When the Kansas City businesswoman Nell Donnelly and her chauffeur were kidnapped in 1931, her lawyer called gangster Johnny Lazia at his desk in the Kansas City Police Department. The boss of the Kansas City mafia had such a cozy relationship with the police that he had "the run of police headquarters, a free hand in hiring police officers, and exclusive control over bootlegging and gambling in Kansas City."

Lazia's men quickly rescued Donnelly, who had been taken by some out-of-town crooks who didn't understand who was boss. Gangsters who stepped in like this were as much interested in protecting their turf as saving victims, though winning points with prominent citizens was no doubt part of the attraction.

Mobsters had an additional reason to look for the Lindbergh baby: They were sick of their bootlegging trucks getting stopped and searched in the roadblocks that had been set up to find the child. So the mob was falling over itself to help out. Al Capone, then incarcerated, offered his own reward, hoping a grateful nation would release him if he saved Charles Lindbergh's child.

Alas, the best efforts of Capone and half the gangsters of the Eastern Seaboard came to naught. Baby Charlie had been taken by criminals not known to the underworld's kings, and he died within hours of being pulled from his crib. (His body was not found until months later, a few miles from the Lindbergh home.) But the kidnappers still claimed a ransom, saying they had the baby. They were tracked down by tracing the serial numbers of the bills used to pay it—something only a federal agency was equipped to do.

That wasn't the only kidnapping that ended badly. Victims who fought back were also likely to die. In November 1933, Brooke Hart, a handsome 22-year-old department store heir, was abducted in San Jose. Yelling for help seems to have sealed his fate: His kidnappers panicked, beat him, and threw him from a bridge. But they still went after the ransom, demanding what would be the equivalent of $4 million today. They were amateurs. The police traced the ransom call and swiftly arrested Thomas Harold Thurmond and John M. Holmes.

The kidnapping and murder of a local golden boy stunned the city. When Hart's body was found two weeks later, public outrage reached a frenzy. An armed mob charged the Santa Clara County Jail, battering down the door with metal pipes. The outmanned sheriff gave little resistance. Thurmond and Holmes were dragged from their cells, beaten, and hanged in the park across the street. A San Francisco radio station covered the lynching live, showing the public's ghoulish attraction to bloody spectacles. (If you think that doesn't fit the Bay Area's hippie-dippie reputation, remember that radio stations in the 1990s had to be deterred from counting down to the 1,000th Golden Gate Bridge suicide.) California Gov. James Rolph praised the mob, calling the lynchings the "best lesson California has ever given the country."

Meanwhile, Hoover won his political battle. Not only did kidnapping become a federal crime, but in 1934 the FBI got the power of arrest—not just in kidnapping cases, but in general. Prior to that, they had to either make citizens' arrests or, in Cox's words, "suffer the indignity of asking the local police (or United States marshals) to make arrests for them."

The war on kidnappers lasted from 1933 to 1936. Cox works her way through some of the biggest kidnappings of the period, with cameo appearances from some of the best-known gangsters—Owney Madden, Ma Barker, Machine Gun Kelly, and John Dillinger. Cox is alert to the role lawyers played on both sides of this, with some eager to see the feds' reach extended while others recoiled at the constitutional implications. One overeager Justice Department attorney announced to a 1933 American Bar Association meeting that they could end the "reign of terrorism" of kidnapping by bringing all law enforcement officers and prosecutors under the command of the president. Other barristers present were horrified by this unconstitutional proposal, and Attorney General Homer Cummings had to travel to the meeting to deal with the outcry. (He distanced himself, and the government, from the idea.)

Despite such qualms about federal overreach, the FBI's involvement in kidnappings increased its presence in the public consciousness. Hoover's army of Brylcreemed G-Men became a part of how America understood law enforcement. It would not be the last time its reach and visibility expanded.

The Snatch Racket: The Kidnapping Epidemic That Terrorized 1930s America, by Carolyn Cox, Potomac Books, 376 pages, $34.95

Show Comments (25)