If Bill Barr Brings Back Federal Executions, Innocent People Will Die

We need to leave ourselves room for making good when we inevitably convict the wrong people.

Why should we be concerned about U.S. Attorney General Bill Barr's proposal last week to resume federal executions for some particularly horrendous crimes? Because there's no reason to believe that the flaws that originally cast doubt on capital punishment have become less of an issue.

In his announcement of resumed executions, Barr focuses on "bringing justice to victims of the most horrific crimes." He wants to begin with prisoners "convicted of murdering, and in some cases torturing and raping, the most vulnerable in our society—children and the elderly."

There's no doubt that we're discussing horrific acts. But can we be sure that we've arrested, tried, and convicted the actual perpetrators?

The proportion of death row inmates executed to those set free isn't exactly encouraging. Since 1972, 1,500 people have been executed in the United States. Over that same time, "166 former death-row prisoners have been exonerated of all charges and set free," according to the Death Penalty Information Center.

Extrapolating from the cases in which death row inmates were proven to have not committed the crimes of which they were convicted, a 2014 study estimated that 4.1 percent of all death row inmates could be exonerated. "We conclude that this is a conservative estimate of the proportion of false conviction among death sentences in the United States," the authors added.

That's an awful lot of people cooling their heels behind bars for crimes they didn't commit.

When former Illinois Gov. George Ryan declared a moratorium on executions, in 2000, he decried his state's "shameful record of convicting innocent people and putting them on Death Row. He said he wouldn't allow executions "until I can be sure that everyone sentenced to death in Illinois is truly guilty."

Capital punishment was formally abolished in Illinois in 2011, inspired by a Chicago Tribune exposé of the human error and malice plaguing the criminal justice system. In the years leading to Ryan's moratorium, 13 state inmates condemned to die had been exonerated instead. Nobody knows how many prisoners who had been executed had not really committed the crimes for which they'd been convicted.

Nothing quite so earthshaking brought about the unofficial suspension of federal executions in 2003, but similar concerns have dogged the practice for every jurisdiction in the country.

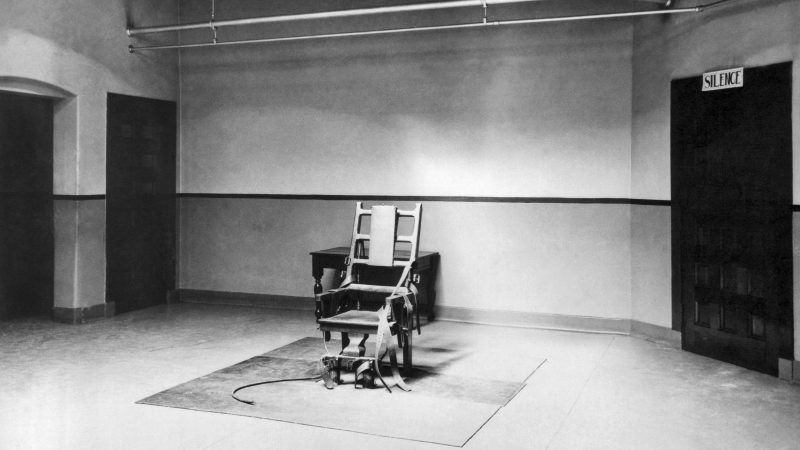

Those concerns about getting it right—imprisoning and killing only criminals guilty of the crimes for which they were convicted—continue to cast a shadow over Barr's plan to resume capital punishment, starting with judicial killings of five inmates.

Nationally, the death penalty was struck down by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1972's Furman v. Georgia over concerns that it was applied in a capricious and discriminatory manner. Further limitations followed in later court cases. And jurisdictions that wished to retain execution as an option reworked their laws in the years that followed to bring their administration of capital punishment into line with the Supreme Court's standards.

The death penalty was restored at the federal level in 1988, and three executions followed: Timothy McVeigh, in 2001: Juan Raul Garza, in 2001; and Louis Jones, in 2003. Without fanfare, the Jones execution was the last such killing by the federal government until—it seems—whatever results from Barr's recent announcement.

The quiet federal moratorium occurred as the criminal justice system across the country came under renewed scrutiny. News reports and independent investigators revealed a litany of tales about incompetent legal representation, lying police, prosecutors suppressing evidence, mentally challenged defendants, dubious crime lab standards, and more. Using relatively new DNA evidence, the Innocence Project boasts of exonerating 365 convicts to-date.

Some of the flaws in the criminal justice system that lead to false convictions are probably inevitable in anything designed by and for imperfect human beings. Others seem fixable, but remain broken because of a lack of political will. In either case, that's plenty of reason to hesitate before imposing an irrevocable penalty on people who might well have been misidentified or even railroaded into convictions for crimes of which they are innocent.

At least something can be done to make things right for the wrongfully convicted and imprisoned. "The federal government, the District of Columbia, and 35 states have compensation statutes of some form," notes the Innocence Project. These jurisdictions offer (often inadequate) monetary compensation, public apologies, counseling, and assistance in reentering society.

In other cases freed inmates have to fight in court to win some redress for the years of their lives stolen from them by the state. But at least they're free and often gain public sympathy.

What do we have to offer innocent people killed by the state because of false convictions for crimes? A lovely bouquet won't do it.

While the evidence suggests that the system is pretty good about getting it right, we do get it wrong. We have lots of room for improvement in the system, including better standards for forensics labs, disincentives to cops to lie and to prosecutors to conceal exculpatory evidence, better legal representation for defendants, and so much more. All of that needs to be done to improve a system that has the inherent power to destroy lives as completely as the the worst criminals it confines do.

Even then, however, we'll never get it completely right. There's always going to be room for malice, incompetence, and corruption. That's why we should punish people for committing the sort of horrendous crimes that Barr highlights while leaving ourselves room to make good when we inevitably convict innocent people.

Show Comments (128)