How Many Drug Offenders Benefited From the Holder Memo That Sessions Rescinded?

The impact of the new charging policy was not as big as the DOJ implied.

For critics of the war on drugs and supporters of sentencing reform, the policy shift that Attorney General Jeff Sessions announced last Friday is definitely a change for the worse. But it's not clear exactly how bad the consequences will be, partly because the impact of the policy he reversed, which was aimed at shielding low-level, nonviolent drug offenders from mandatory minimum sentences, is hard to pin down.

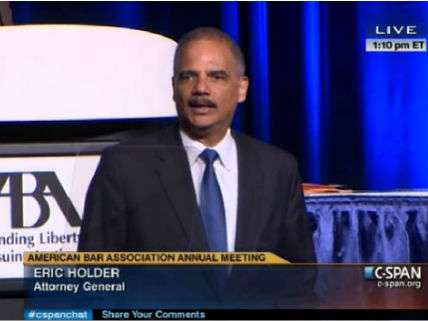

Sessions rescinded a 2013 memo in which Attorney General Eric Holder encouraged federal prosecutors to refrain from specifying the amount of drugs in cases involving nonviolent defendants without leadership roles, significant criminal histories, or significant ties to large-scale drug trafficking organizations. Since mandatory minimums are tied to drug weight, omitting that detail avoids triggering them.

Numbers that the Justice Department cited last year suggest Holder's directive, which was the heart of his Smart on Crime Initiative, had a substantial effect on the percentage of federal drug offenders facing mandatory minimums. According to data from the U.S. Sentencing Commission (USSC), the share of federal drug offenders subject to mandatory minimums has fallen steadily since Holder's memo, from 62 percent in fiscal year 2013 to less than 45 percent in fiscal year 2016. If the percentage had remained the same, more than 10,000 additional drug offenders would have fallen into that category during this period.

"The promise of Smart on Crime is showing impressive results," Deputy Attorney General Sally Q. Yates said last year, citing the USSC numbers through fiscal year 2015. "Federal prosecutors are consistently using their discretion to focus our federal resources on the most serious cases and to ensure that we reserve harsh mandatory minimum sentence for the most dangerous offenders."

Counterintuitively, however, the defendants whom the USSC describes as "drug offenders receiving mandatory minimums" include drug offenders who did not actually receive mandatory minimums. Many of them were convicted under provisions that call for mandatory minimums yet escaped those penalties because they offered "substantial assistance" or qualified for the statutory "safety valve."

Paul Hofer, a policy analyst at Federal Public and Community Defenders, took those other forms of relief into account in a 2013 estimate of the Holder memo's possible impact. In fiscal year 2012, Hofer found, "6,780 defendants convicted under drug statutes carrying a mandatory minimum penalty appeared to meet the memo's measurable criteria," but "most of these already receive[d] some form of relief from the mandatory minimum penalties." All but 868 of those defendants were already eligible for relief, and judges gave 467 of them sentences longer than the mandatory minimums, which suggests the new rule would not have helped them.

In addition to 401 qualifying defendants otherwise ineligible for relief who "had drug statutory minimums that were higher than the otherwise applicable guideline minimums," Hofer counted 129 who "had statutory minimums lower than the guideline range and received the maximum downward departure or variance possible prior to the memo." He said "these defendants seem likely to have received greater reductions if the limitation on judicial discretion were removed." That's a total of 530 defendants who "would likely have received a lower sentence if the Holder memo had been in effect in FY 2012." Hofer's analysis suggests that the vast majority of drug offenders who seem to have benefited from the 2013 memo—thousands each year—did not actually receive shorter sentences as a result of the policy change.

Then again, the benefits of Holder's memo may extend beyond the federal defendants who avoided mandatory minimums. By encouraging prosecutors to focus their efforts on the most serious drug offenders, Holder may have indirectly reduced punishment by allowing some people to avoid federal charges altogether. That instruction may help explain why the total number of federal drug cases fell from 25,000 in fiscal year 2013 to 21,387 in fiscal year 2016, a 14 percent drop.

As Molly Gill, director of federal legislative affairs at Families Against Mandatory Minimums, points out, there is some evidence that federal prosecutors did try to focus on the most serious cases: During the same period, the share of defendants benefiting from the safety valve (which excludes high-level and violent offenders) fell from 24 percent to 13 percent. "With the directive not to slam low-level drug defendants," says University of California at Irvine criminologist Mona Lynch, "there was likely some shift toward bringing more serious cases and simply passing on smaller, street-dealing type of cases."

Sessions is now telling federal prosecutors to pursue the most serious provable charges against drug offenders (and other federal defendants) unless they believe an exception to that policy is warranted, in which case they have to seek permission from their supervisors and justify the decision in writing. Although Sessions argues that the new default rule will produce more uniform results, Lynch thinks it could have the opposite effect.

"The big question is whether he has the power to roll back time and change the prevailing legal culture that has tempered the 'drug war' mentality of the 1990s in many federal jurisdictions," says Lynch, who studied the behavior of federal prosecutors for her 2016 book Hard Bargains: The Coercive Power of Drug Laws in Federal Court. "Even under a more stringent set of charging policies…U.S. attorneys have considerable discretion as to what cases to bring….This policy may only increase the divide between jurisdictions that collectively eschew aggressive federal drug prosecutions and those that dive back into the harsh practices of an older era. This would result in even more geographic disparity in federal justice outcomes, a longstanding concern of Congress and of the U.S. Sentencing Commission."

Douglas Berman, a sentencing expert at Ohio State's Moritz College of Law, argues that the general message sent by Holder, and now by Sessions, is more important than the details of their instructions. "The tone/attitude of DOJ ultimately matters even more than the particulars of the memo," Berman says. "Things got a lot more lenient during Obama's second term in part because a signal was coming from everyone that federal prosecutors should be a lot more lenient, and the Holder memo was most essential piece of this story for prosecutors. Things are likely to get tougher during Trump's first term, but how much tougher is going to depend a lot on whether others formally and informally jump on the toughness bandwagon."

Show Comments (10)