Hillary Clinton's Kinder, Gentler War on Drugs Sounds Like Nixon's

The presumptive Democratic nominee promises to eliminate addiction once and for all.

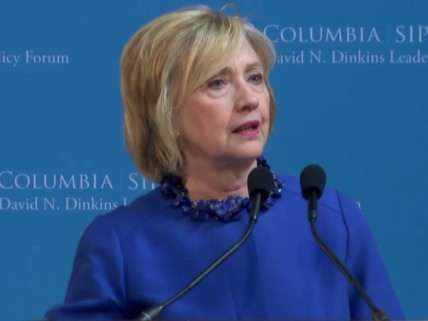

Yesterday Hillary Clinton described the approach to drug policy she plans to take if she is elected president, and it looks a lot like Richard Nixon's. Despite his reputation as a hardline law-and-order demagogue who started the modern war on drugs, Nixon was big on drug treatment, and so is Clinton. Nixon drew a distinction between the addicts who deserve our compassion and the traffickers who belong in prison, and so does Clinton. Nixon expressed qualms about excessively harsh penalties for low-level drug offenders, and so does Clinton. Nixon had no doubts about the morality of using violence to stop people from consuming arbitrarily proscribed psychoactive substances, and neither does Clinton.

Clinton tries to present her war on drugs as a service to its targets:

Twenty-three million Americans suffer from addiction, but only 1 in 10 get treatment….

This is not new. We're not just now "discovering" this problem. But we should be saying enough is enough. It's time we recognize as a nation that for too long, we have had a quiet epidemic on our hands. Plain and simple, drug and alcohol addiction is a disease, not a moral failing—and we must treat it as such.

No doubt most drug offenders would prefer to be treated like patients rather than criminals. But in practice, they are treated like both. When Clinton says "our state and federal prisons…are no substitute for proper treatment," when she talks about "ensur[ing] every person suffering from addiction can obtain comprehensive treatment" and "prioritiz[ing] treatment over prison for low-level and nonviolent drug offenders," what she has in mind is, at best, giving consumers of politically incorrect intoxicants a choice between a treatment slot and a jail cell.

Despite Clinton's reference to "alcohol addiction," that is not a choice that even the heaviest drinker has to confront unless he commits a crime. Drinking itself, unlike the use of illegal drugs, does not qualify. A corollary is that even casual drug users with no addiction to treat may still have to choose between treatment and jail if they happen to get caught.

Clinton does not bother to defend this blatantly unequal approach, because it is indefensible. It is therefore hard to take seriously her pose as an enlightened, compassionate public servant who only wants to help "sick people that deserve to get well." This medicalization of drug policy may take some of the rough edges off the war on drugs (or not), but only at the cost of denying the moral agency of drug users, which justifies the government's shabby and often brutal treatment of them.

Clinton's conflation of coercive paternalism with voluntary medical treatment is especially troubling given her pie-in-the-sky ambitions. "There are 23 million Americans suffering from addiction," she writes. "But no one is untouched. We all have family and friends who are affected. We can't afford to stay on the sidelines any longer—because when families are strong, America is strong. Through improved treatment, prevention, and training, we can end this quiet epidemic once and for all."

If you elect Hillary Clinton, she will wipe out addiction. I'm not sure which is scarier: that Clinton thinks this hubristic mission will appeal to voters, or that if she is elected she might actually attempt it.

Show Comments (54)