Indiana's Revised RFRA Law Strikes the Worst Possible Balance

The threat of a corporate boycott has sacrificed religious liberties without protecting gays

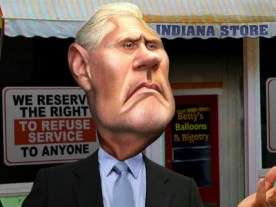

Indiana Gov. Mike Pence (R) vowed to "clarify and fix" his state's new Religious Freedom and Restoration Act after major corporations threatened to boycott the state. And so he did—by completely gutting the law.

These businesses—and many caterwauling progressives—claimed that the original law gave religiously inclined business owners a "license to discriminate," especially against gay customers. But the amended law maximizes the damage on both ends: It undermines the rights of religious businesses without protecting gays from discrimination.

However, what is deeply ironic is that corporate America was able to wield its right not to do business (and boycott Indiana) by circumscribing the same right of Indiana businesses.

Indiana is hardly the first state to embrace a law like RFRA. The federal government—and 19 other states—already have RFRA laws on the books. But the reason that the Hoosier State's law has produced what The Week's Michael Brendan Dougherty aptly dubbed a "national freak-out" is that these other laws mostly protect individuals seeking relief from government intrusions into their religious beliefs. For example, thanks to the federal RFRA, Uncle Sam can't deny unemployment benefits to American Indians who consume an illegal hallucinogen like peyote during religious ceremonies because that would unduly burden the right to the free exercise of their religion.

The Indiana law went farther, and also applied to disputes between private parties. This "would allow people to discriminate against their neighbors," alleged Apple CEO Tim Cook, who has become a liberal hero by leading the corporate opposition against the law.

This is a horrible caricature.

For starters, the Hoosier RFRA allowed private individuals to discriminate only when that was absolutely necessary to avoid violating their core religious principles. A Christian restaurant owner's refusal to serve gays wouldn't fit the bill. However, a Jewish baker who refused to make sacramental bread for a Catholic Mass or an Evangelical photographer who declined to photograph a gay wedding might—might, mind you, not would. That's because the law provided merely an argument for courts to weigh when evaluating discrimination complaints against such individuals—not an automatic defense. Judges could still decide that equal treatment was a compelling enough government interest that such discriminatory actions against gays are prohibited.

There would be an argument to deny business owners even this little space to live by their spiritual sensibilities if the discriminated individuals couldn't obtain the services they needed elsewhere—as was the case with blacks in the Jim Crow South prior to the passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act. But discrimination isn't as institutionalized now as it was then, especially against gays, who have gained rapid acceptance in recent years. If one establishment refuses to service gay customers, there are myriad others that will, imposing no severe hardship on them. To insist on being served by the few people whose beliefs would be violated seems more like a projection of power rather than a plea to secure legitimate rights.

Furthermore, if corporations merely boycotted Christian businesses whose beliefs they found abhorrent, it would be one thing. But what's truly obnoxious about their campaign was that they were using their right not to do business with Indiana, because it was doing something they disagreed with, to obtain a law that would deny Indiana businesses the same right not to do business with folks who they don't agree with. This is simply intolerance masquerading as a crusade for justice and equality—a naked use of brute market power to legislate his views.

That said, the "national freak-out" against Indiana hasn't emerged in a vacuum. Gov. Pence unsuccessfully tried to outlaw gay marriages in Indiana, after all. So there is little reason for gays to trust him, notwithstanding his protestations that he found discrimination against gays personally abhorrent.

Also, the state doesn't have a statute barring discrimination by sexual orientation or gender identity in housing, education, and public accommodation as it does by race. So if Indiana were striving to balance religious liberties and equal treatment of gays, it would have made sense for it to pass such a law but leave RFRA alone, which is sort of what Utah has done. "The state passed new religious-conscience accommodations, but they were tied to new gay-rights protections," Brooking Institute's Jonathan Rauch has noted.

Such an approach would have offered gays standing protections against discrimination, but allowed judges to use RFRA to carve out exceptions for religious conscientious objectors on a case-by-case basis if they could offer strong reasons why discrimination was necessary to maintain some central tenet of their faith, balancing both sides' interests.

This wouldn't be ideal from a libertarian standpoint because, in a free society, people should be free to not associate with someone, even for the most odious reasons. But it wouldn't be the worst thing either. Indiana's "fix", however, strikes the worst possible compromise. It won't make it illegal to discriminate against gays (except in communities such as Indianapolis that have such laws) but it'll take away a potential legal defence from those who do, sowing confusion and frustration.

This isn't a worthy compromise for a nation founded on the promise of protecting religious liberty and ensuring equality. But if the nation's corporations are pleased, who cares, right?

A version of this column originally appeared in The Week.

Show Comments (57)