'Mexican, Crazed by Marihuana, Runs Amuck With Butcher Knife'

Highlights from the anti-pot files of The New York Times

According to a recent poll by the Pew Research Center, 54 percent of American adults support marijuana legalization. That's around 130 million people. It turns out that some of them are members of the New York Times editorial board, which last week declared that "the federal government should repeal the ban on marijuana."

Given its timing, the paper's endorsement of legalization is more an indicator of public opinion than a brave stand aimed at changing it. Andrew Rosenthal, editorial page editor at the Times, told MSNBC's Chris Hayes that the new position was not controversial among the paper's 18 editorial writers and that when he raised the subject with the publisher, Arthur Sulzberger, "He said, 'Fine.' I think he'd probably been there before I was. I think I was there before we did it." Better late than never, I guess, although I confess that seeing a New York Times editorial in favor of legalizing marijuana briefly made me wonder if I've been wrong about the issue all these years.

In their gratitude for the belated support of a venerable journalistic institution, antiprohibitionists should not overlook the extent to which the Times has aided and abetted the war on marijuana over the years. That shameful history provides a window on the origins of this bizarre crusade and a lesson in the hazards of failing to question authority.

In an essay published by the Times on Tuesday, part of a series fleshing out the case for legalization, editorial writer Brent Staples exposes the ugly roots of marijuana prohibition: "The federal law that makes possession of marijuana a crime has its origins in legislation that was passed in an atmosphere of hysteria during the 1930s and that was firmly rooted in prejudices against Mexican immigrants and African-Americans, who were associated with marijuana use at the time. This racially freighted history lives on in current federal policy, which is so driven by myth and propaganda that it is almost impervious to reason."

Unfortunately, Staples overlooks the role the Times itself played in building that atmosphere of hysteria and disseminating the propaganda that supposedly justified the ban on marijuana. He mentions "sensationalistic newspaper articles" that tied marijuana to "murder and mayhem" and "depicted pushers hovering by the schoolhouse door turning children into 'addicts.'" He does not mention that such stories appeared in The New York Times.

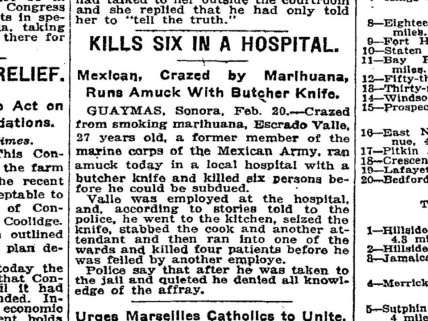

In February 1925, as states were beginning to ban marijuana, the Times reported that a 27-year-old Mexican named Escrado Valle, "crazed from smoking marihuana," "ran amuck today in a local hospital and killed six persons before he could be subdued." Later that year it announced that the Mexican government had banned marijuana "To Stamp Out Drug Plant Which Crazes Its Addicts." In 1927 the Times picked up on the theme of marijuana-crazed Mexicans again, reporting that "a widow and her four children have been driven insane by eating the Marihuana plant." The paper cited "doctors" who "say that there is no hope of saving the children's lives and that the mother will be insane for the rest of her life." Yet according to the story, the family accidentally ate fresh cannabis plants, which are not psychoactive.

Stories like these helped pave the way for prohibition by portraying cannabis, which had been widely used in American patent medicines, as an exotic, madness-inducing, potentially deadly drug favored by brown-skinned foreigners. Another important element of the pot panic: This insidious plant supposedly was invading schoolyards across America. In 1934, three years before Congress approved the Marihuana Tax Act (a de facto ban), the Times reported that Harry J. Anslinger, who was instrumental in stirring up cannaphobia as head of the Federal Bureau of Narcotics (FBN), "is investigating the use by school children in Cleveland and other areas of marihuana, a mild narcotic reported to change the qualities of valor and courage to fear and even insanity."

The claim that cannabis replaces courage with fear seems inconsistent with the marijuana-induced mass murder that the Times had reported a decade before. It also seems inconsistent with the FBN's claim that "prolonged use of Marihuana frequently develops a delirious rage which sometimes leads to high crimes such as assault and murder," which is why "Marihuana has been called 'the killer drug.'"

In 1937, the year that Congress banned marijuana, the Times referred matter-of-factly to "the devastating effects of the marihuana weed" in a story about an educational program aimed at "bringing home to young people not already acquainted with marihuana the reasons for its general designation as 'the killer drug.'" A few months later the Times identified marijuana as "the new narcotic menace to youth" in an article that relied heavily on an anti-pot agitator who "characterized marihuana as the 'most pernicious' of drugs" and "said it produced in smokers of the weed a temporary sense of complete irresponsibility which led to sex crimes and other 'horrible' acts of violence."

Did people actually believe these terrifying tales? Apparently they did. In 1938 the Times reported on a murder trial in which one of the defendants "contended she was a victim of marihuana madness."

What a relief, after all that fear mongering, to come across a 1938 New York Times review of Robert P. Walton's book Marihuana: America's New Drug Problem. "Over the last year," the review begins, "the growing abuse of marihuana has been sensationally publicized in newspapers, magazines and on the screen." Finally, a voice of reason.

Or maybe not. The author of the review, Frederick T. Merrill, claims "the hashish vice…has assumed alarming proportions in this country." He adds that "depravity has been and still is the only motive for [marijuana's] habitual use, and its effects are particularly anti-social." Merrill—who four years later published Japan and the Opium Menace, a book that Foreign Affairs called "a factual study of one of Japan's most dangerous weapons"—assures anyone skeptical of Anslinger's claims about marijuana-related violence that science is on Anslinger's side: "The reason why marijuana and crime are so closely linked is more understandable in view of the unpredictable reactions to varying quantities of the drug."

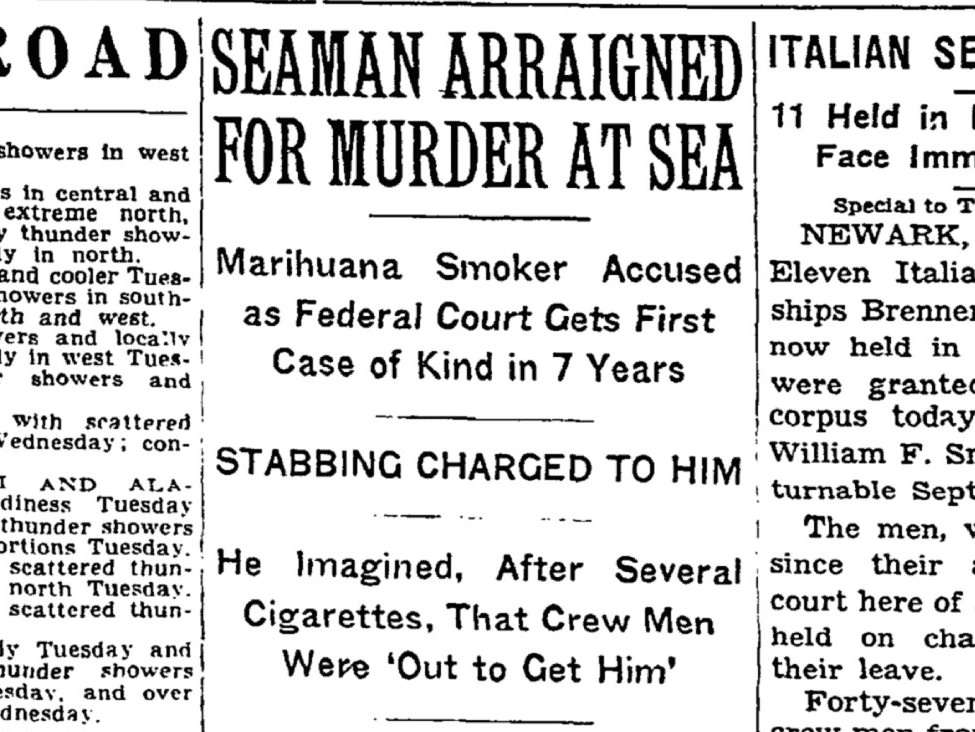

As late as 1941, the Times was still lending credence to the idea that marijuana makes men murder. "Seaman Arraigned for Murder at Sea," the headline over a news story published that year announced. "Marihuana Smoker Accused as Federal Court Gets First Case of Kind in 7 Years; Stabbing Charged to Him; He Imagined, After Several Cigarettes, That Crew Men Were 'Out to Get Him.'"

In fact, the Times continues to run such stories from time to time, albeit under less sensational headlines. A May 31, 2014, article headlined "After 5 Months of Sales, Colorado Sees Downside of a Legal High" included this sentence: "There is the Denver man who, hours after buying a package of marijuana-infused Karma Kandy from one of Colorado's new recreational marijuana shops, began raving about the end of the world and then pulled a handgun from the family safe and killed his wife, the authorities say."

To be clear: I am not saying that didn't happen; I am merely questioning the implication that marijuana made him do it. As with Escrado Valle, the man who reportedly ran amuck in a Mexican hospital back in 1925, the story is probably a bit more complicated than that.

Uncritically regurgitating anti-drug horror stories has practical implications, and they are not pretty. In a 1951 story headlined "Fight Against Narcotics Waged by U.S. and U.N.," the Times reported that "Congress will be called upon shortly to consider a bill which experts believe will go further toward stamping out the narcotics evil in this country than anything since the Harrison Narcotics Act." It was referring to the Boggs Act, which established mandatory minimum sentences for federal crimes involving marijuana and other illegal drugs. According to Harry Anslinger, the enhanced penalties, precursors to the draconian sentences that in recent years have drawn bipartisan criticism, were necessary to win the "battle with the drug traffic."

Almost two decades later, the Times still thought "the penalties for those who prey on the innocent by peddling drugs can hardly be too severe," although it simultaneously urged "a distinction between soft and hard drugs." That 1969 editorial is part of a collection assembled by the Times to illustrate its "evolving" position on marijuana.

The collection, which spans five decades, includes a 1966 editorial rejecting Timothy Leary's "specious" claim that freedom of conscience should include the freedom to alter your consciousness. "Experience has tragically demonstrated that marijuana is not 'harmless,'" the Times declared. "For a considerable number of young people who try it, it is the first step down the fateful road to heroin." That claim was echoed by a front-page story that ran several days later under the headline "Drugs a Growing Campus Problem." Reporter John Corry allowed that "student pot parties, those wild abandoned orgies in which no man's daughter is safe, seem to exist more in fancy than in fact." But that does not mean "marijuana cannot be dangerous," Corry warned:

A significant number of marijuana smokers will go on to heroin, the Bureau of Narcotics says. "Potsville," the narcotics agents say, "leads to the mainline."

As of this week, however, the Times admits "claims that marijuana is a gateway to more dangerous drugs are as fanciful as the 'Reefer Madness' images of murder, rape and suicide."

Although the Times was not ready to let Leary off the hook for marijuana possession in 1966, three years later it urged Congress to "lighten the penalty for mere possession," which at the time (as a result of the Boggs Act) carried a mandatory minimum sentence of two years. By 1970 the Times was wondering whether the law should "continue to treat [marijuana] in the same manner as heroin," although "this is not to say that marijuana should be legalized"—a policy that at that point was supported by only 15 percent of Americans, according to the Gallup Poll. The following year, theTimes clarified its position. "Marijuana is not a 'narcotic,'" it said, "but it is a dangerous drug," although not so dangerous that simple possession merits a one-year sentence.

In 1972, reacting to the conclusions of the National Commission on Marijuana and Drug Abuse, the Times suggested that "the dangers inherent in smoking marijuana appear to be less than previously assumed." It agreed with the commission that criminal penalties for possession and use should be eliminated. As for "outright legalization," the Times said "the accumulation of further medical evidence might justify such a step later on."

In 1978 the Times said marijuana "shows great, though not fully proven, potential as a therapeutic agent." But legalizing marijuana for medical use "would be premature," it said, calling for more research. Eighteen years later, responding to the passage of medical marijuana initiatives in California and Arizona, the Times was still calling for more research. In the meantime, it said, the Clinton administration's "aggressive campaign to combat the state initiatives…makes sense."

The paper's reaction to the 2012 initiatives that legalized marijuana for recreational use in Colorado and Washington was less hostile. Last September the Times urged the Justice Department to "start filling in the details" of its response to those developments, but it did not take a position on whether legalization, or even allowing it to happen, was a good idea. A couple of months later, the Times noted the possibility that marijuana legalization could reduce traffic fatalities if it leads to less drinking. "That could be good news," it admitted. Last January the Times marked the beginning of recreational marijuana sales in Colorado with another noncommittal editorial, suggesting "what to watch for in the early stages of this experiment." As Rosenthal put it on MSNBC, "We have been careful and cautious on this issue."

In short, the Times first publicly toyed with the idea of marijuana legalization in 1972, but it did not get around to endorsing that policy until 42 years later. What happened in between? Jimmy Carter, a president who advocated decriminalization, was replaced in 1981 by Ronald Reagan, a president who ramped up the war on drugs despite his lip service to limited government. That crusade was supported by parents who were alarmed by record rates of adolescent pot smoking in the late 1970s. Gallup's numbers indicate that support for legalizing marijuana, after rising from 12 percent in 1969 to 28 percent in 1978, dipped during the Reagan administration, hitting a low of 23 percent in 1985 before beginning a gradual ascent.

Legalization did get at least a couple of positive mentions on the New York Times editorial page during the 1980s. A 1982 essay actually advocated "regulation and taxation" as "a more sensible alternative" to decriminalization, arguing that "a prohibition so unenforceable and so widely flouted must give way to reality." But that piece was attributed only to editorial writer Peter Passell, so it did not represent the paper's official position. Four years later, an editorial that was mainly about drug testing asked, "Why not sharpen priorities by legalizing or at least decriminalizing marijuana?" Good question. Let's think about it for a few decades.

The executive editor of the Times during this period, Abe Rosenthal (Andrew's father), was a passionate prohibitionist, a fact that became clear when he started writing a twice-weekly column for the paper in 1987. The column was officially called "On My Mind," but Rosenthal's detractors renamed it "Out of My Mind" because of its vitriolic, hyperbolic tone. In retrospect, Rosenthal's fulminations against drug policy reformers marked the beginning of the end for marijuana prohibition, which became steadily less popular during the next few decades, to the point that Rosenthal's son and his colleagues on the editorial board finally felt comfortable expressing their views on the issue.

It took almost a century for The New York Times to go from credulously accepting anti-marijuana propaganda to contemptuously rejecting it, along with the ban built on that foundation of lies. Which raises the obvious question: If the Times could be so wrong for so long about marijuana, what other mistakes has it made in covering and commenting on drug policy? Plenty, including exaggerating the hazards of pretty much every drug that has ever been a subject of public concern while conflating the effects of drug use with the effects of prohibition. The corrections may take a while.

This article originally appeared at Forbes.

Show Comments (12)