No, ICE Agents Do Not Have 'Absolute Immunity' From State Prosecution

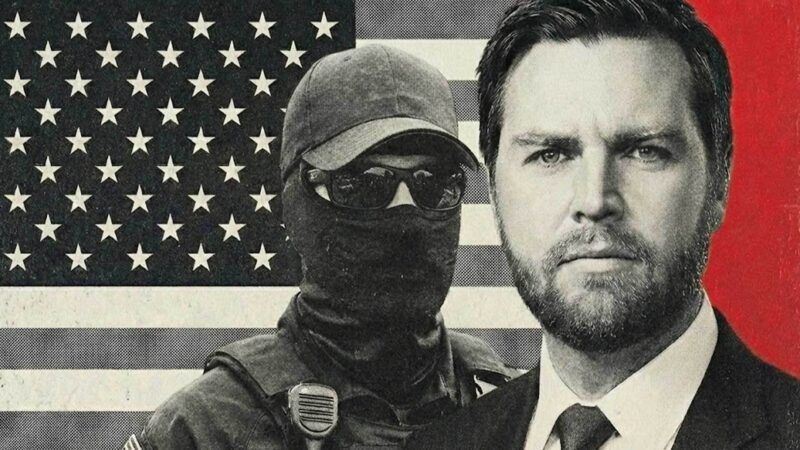

How J.D. Vance misstated the law.

According to Vice President J.D. Vance, the Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) officer who shot and killed Renee Nicole Good in Minneapolis cannot be prosecuted for it by Minnesota officials. "The precedent here is very simple," Vance declared. "You have a federal law enforcement official engaging in federal law enforcement action—that's a federal issue. That guy is protected by absolute immunity. He was doing his job."

But the precedent is not actually so simple. In an 1890 case known as In re Neagle, the U.S. Supreme Court held that a federal marshal named David Neagle was "not liable to answer in the Courts of California" after he fatally shot the would-be assassin of a Supreme Court justice named Stephen Field during an attack on Field that occurred on a train traveling through California (Neagle was present as Field's official bodyguard). "Under the circumstances," the Court said, Neagle "was acting under the authority of the law of the United States, and was justified in so doing." Therefore, "he is not liable to answer in the courts of California on account of his part in that transaction."

Vance may have been thinking of In re Neagle when he claimed that ICE agents possess "absolute immunity" from state prosecution. However, In re Neagle was not the Supreme Court's final word on the matter.

You’re reading Injustice System from Damon Root and Reason. Get more of Damon’s commentary on constitutional law and American history.

Sixteen years later, in Drury v. Lewis (1906), the Supreme Court allowed a state court to weigh murder charges filed by local officials against a U.S. soldier over the killing of a man suspected of stealing copper from a federal arsenal in Pennsylvania.

As part of the legal briefing in that case, Assistant Attorney General Milton Purdy cited In re Neagle in support of a Vance-like argument that called for shielding the soldier from any and all state prosecution. Here is how that argument is summarized in the U.S. Reports:

Even though [the soldier] used more force in attempting to make the arrest than he was warranted in using under the law, nevertheless since he was engaged in performing a duty imposed upon him by a law of the United States, the state courts are without jurisdiction to call him to account for the excessive use of force in performing a duty which the Federal laws commanded.

But the Supreme Court declined to adopt that sweeping argument in Drury v. Lewis. Instead, the Court held that the guilt or innocence of the soldier "was for the state court if it had jurisdiction, and this the state court had, even though it was [the soldier's] duty to pursue and arrest [the suspect] (assuming that he had stolen pieces of copper), if the question of [the suspect] being a fleeing felon was open to dispute on the evidence."

In other words, even if the soldier was doing his job by chasing down the suspect, the state court still had jurisdiction if the lawfulness of the soldier's use of force against the suspect "was open to dispute on the evidence."

And it was open to such dispute. According to some witnesses, the soldier did not shoot a "fleeing felon" at all; rather, those witnesses said the soldier only shot the man after he had surrendered. The Supreme Court thus left it up to a state court (and state jury) to untangle the thorny dispute over lawful versus unlawful use of force by the soldier. The state murder trial was free to proceed.

In short, Vance's blanket assertion that federal agents enjoy "absolute immunity" from state prosecution is contradicted by Drury v. Lewis and is therefore unsound as a statement of law.

Show Comments (111)