A School District Cop Allegedly Did Nothing To Stop the Uvalde Mass Shooting. Was That Failure a Crime?

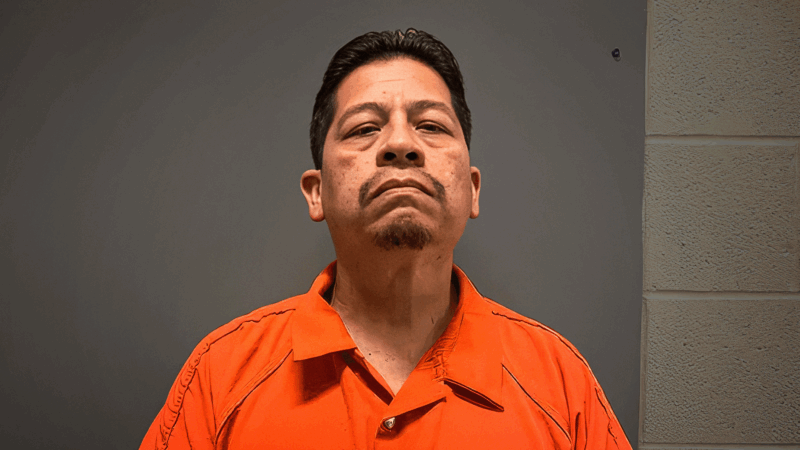

Adrian Gonzales is on trial for acts of "omission" that prosecutors say amounted to 29 felony counts of child endangerment.

After the 2022 shooting that killed 19 students and two teachers at Robb Elementary School in Uvalde, Texas, police officers were widely condemned for failing to act in time to prevent those deaths. The gunman was not stopped until 77 minutes after the assault began, when members of the U.S. Border Patrol Tactical Unit breached a classroom door and shot him dead.

Outrage at the timid, desultory response to that attack resulted in criminal charges against Pete Arredondo, the school district's police chief, and one of his officers, Adrian Gonzales, whose trial began this week in Corpus Christi. Gonzales, who was suspended along with the rest of the department after the shooting and had officially left his job by the beginning of 2023, faces 29 counts of child endangerment—one for each of the 19 fourth-graders who were killed and one for each of the 10 students who survived. Since each count is a state jail felony punishable by six months to two years of incarceration, Gonzales could receive a lengthy sentence if he is convicted. But while the anger underlying this case is understandable, the legal basis for it is dubious.

An indictment that an Uvalde County grand jury approved in June 2024 cites Article 22.041(c) of the Texas Penal Code, which applies to someone who "intentionally, knowingly, recklessly, or with criminal negligence, by act or omission, engages in conduct that places a child" in "imminent danger of death, bodily injury, or physical or mental impairment." According to the indictment, Gonzales did that by failing to intervene in a way that might have impeded or stopped the gunman.

The indictment says Gonzales, one of the first officers to arrive at the scene, heard gunshots outside the school, knew "the general location of the shooter," and had "time to respond." Yet he "failed to engage, distract or delay the shooter" or try to do so "until after" the gunman entered two classrooms and started shooting the children there. He also allegedly "failed to follow" or "attempt to follow" his "active shooter training."

Special prosecutor Bill Turner elaborated on that description in his opening statement at the trial on Tuesday, saying a coach at the school directed Gonzales toward the gunman. "His shots are ringing out," and Gonzales "knows where [he] is" yet "remains at the south side of the school" while "the gunman makes his way up the west side of the west building where the fourth-graders are," Turner said. Gonzales stayed where he was, Turner added, even after the gunman "fired shots into a classroom full of children" from outside, after he fired into another classroom, and after he entered the school, when there was "a break in the shooting."

All of that, if true, is reprehensible and ample cause for dismissal. But is it a crime?

Sam Bassett, an Austin attorney with 38 years of experience in criminal defense, says he has never seen a case where a police officer was successfully prosecuted for such failures. "It is a very novel prosecution, no question," says Bassett, a former president of the Texas Criminal Defense Lawyers' Association. "From a legal standpoint, it's a real leap to say he had a duty to act in this context."

Without such a duty, Bassett explains, the acts of "omission" described in the indictment cannot justify a child endangerment conviction. "An omission is not any kind of a crime unless there's a specific duty to act," he says.

Generally speaking, police officers do not have a legal obligation to protect crime victims from harm. In the 1981 case Warren v. District of Columbia, for example, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit held that police had "no specific legal duty" to protect three women who were kidnapped from their home, assaulted, and raped. "The duty to provide public services is owed to the public at large," the appeals court said, "and, absent a special relationship between the police and an individual, no specific legal duty exists."

In the 2005 case Castle Rock v. Gonzales, the Supreme Court held that a woman did not have a cause of action under the 14th Amendment's Due Process Clause against a Colorado town where police failed to enforce a restraining order against her estranged husband, who had abducted their three children and ultimately murdered them. The fact that state law ostensibly required police to act in such circumstances did not change the analysis, Justice Antonin Scalia said in the majority opinion, because "a well established tradition of police discretion has long coexisted with apparently mandatory arrest statutes."

A 2020 ruling by the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 11th Circuit seems especially relevant to the case against Adrian Gonzales. Students who survived the 2018 mass shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida, sued Broward County and several local officials "on the theory that their response to the school shooting was so incompetent that it violated the students' substantive rights under the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment." A federal judge dismissed that claim with prejudice, and the 11th Circuit upheld that decision, saying "caselaw makes clear that official acts of negligence or even incompetence in this setting do not violate the right to due process of law."

The criminal case that most closely resembles the charges against Gonzales also grew out of the Parkland shooting. Scot Peterson, a school resource officer who, like Gonzales, was accused of failing to intervene and failing to follow his training, was charged with seven counts of felony child neglect and three counts of culpable negligence. A jury acquitted him of all charges in June 2023.

In that case, prosecutors likewise argued that Peterson had a duty to act. The jury evidently disagreed.

Whether Gonzales had a specific duty to act is "a fact issue for the jury to decide," Bassett says. "The jury instruction in the case will be very interesting [because it] will have both the law and an application of the law to the facts of the situation."

The trial is expected to take a couple of weeks. At its conclusion, the defense can ask the judge, Sid Harle, for a directed verdict of not guilty based on the argument that the evidence is legally insufficient to establish the elements of the crime. Bassett notes that Harle, whom he describes as "a great judge" who is "highly competent," is retired and sitting by appointment. "He has no political capital anymore," Bassett says, "so he's not going to care about what people think of him. He's going to try to do the right thing, in my experience."

Bassett thinks proving child endangerment will be a tall order. "It's definitely an emotional situation," and the police surely "can be criticized" for the inadequacy of their response to the shooting, he says. "But to say he's guilty of a felony in this context is another fence to leap over."

Show Comments (83)