How the Punisher, a Murderous Anti-Hero, Became the Mascot for Increasingly Militarized Police Forces

“He is breaking the very laws…that cops are supposed to uphold.”

In 2015, actor Jon Bernthal appeared at New York Comic Con soon after the announcement that he would portray Marvel Comics' famous vigilante the Punisher in the Netflix series Daredevil. "I know how important he is to law enforcement, to the military," he told the crowd. "I look at this as a huge honor, a huge responsibility. And I give you my absolute word, I'm gonna give everything that I have."

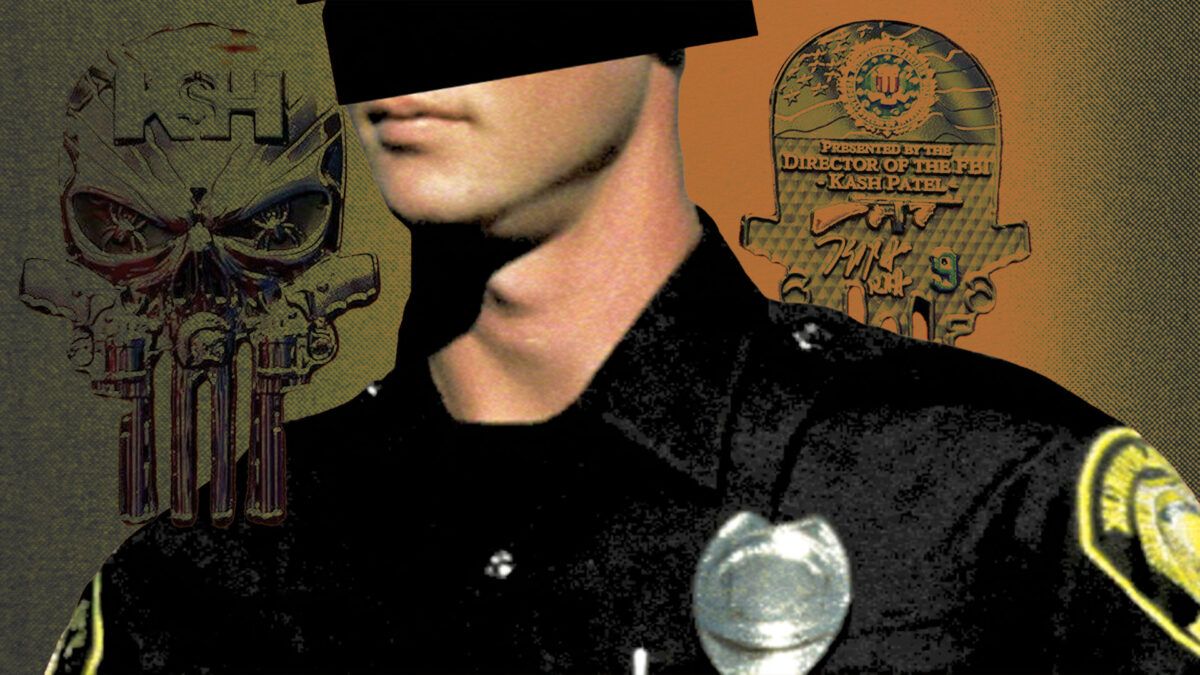

Since then, Punisher iconography has only continued to proliferate among police officers. The character's skull logo has become synonymous with uncritical support for police. Even FBI Director Kash Patel is a fan. In October, MSNBC's Ken Dilanian shared a photo of a challenge coin Patel had given out featuring a skull that greatly resembled the Punisher symbol. That trend is disheartening, both for fans of the comics character, like me, and for Americans who want a sane law enforcement apparatus dedicated to serving citizens rather than unleashing violence.

Unlike most of his superhero compatriots, the Punisher is an unrepentant murderer, focused less on restorative justice than on simply massacring his enemies. He is quite possibly the worst role model comics have ever produced. While sometimes a thrilling story of a man able to right the wrongs he sees in the world, the Punisher also functions as an indictment of feckless or corrupt police and a military that sends people off to kill but does too little when they come home damaged. Some of the people who lionize the character these days miss that point—to our detriment.

As a teenager, I found the Punisher's brutally uncompromising Manichaean worldview a fascinatingly stark contrast to other, more optimistic comic book heroes. The Punisher inhabited that same world but seemed to flout all its rules and conventions: He had no superpowers other than military training, a seemingly unlimited arsenal, and tenacity. I've accrued numerous issues of Punisher comics and collectibles and multiple T-shirts bearing his signature skull logo.

But in the more than two decades since I picked up my first issue at the local grocery store, the character's cultural meaning has shifted. For years, the people most likely to wear the skull logo were comic fans like me; then, over time, it became noticeably more popular among police officers. Custom shops such as Etsy and Redbubble, and mass retailers such as Amazon, carry thousands of items printed with Punisher skulls, often combined with American flags and pro-police iconography.

"There has to be a recognition that while he's doing what they want to fantasize about doing, that he's wrong," Punisher co-creator Gerry Conway tells Reason. "He is breaking the very laws, for example, that cops are supposed to uphold. So, putting a Punisher decal on your cop car is saying you want to break the rules and you want to be outside the law."

A Unique Character in Superhero Comics

"He's this normal street-level guy in this world of gods and monsters and marvels," says David Pepose, who wrote the 2024 Punisher comic series. While benevolent heroes fly through the sky overhead, "the Punisher's the guy in the gutters. He's seeing the worst of the worst."

The character, born Frank Castle, debuted in a 1974 issue of The Amazing Spider-Man as a mercenary hell-bent on killing criminals—"a warrior fighting a lonely war," as he put it, who "kill[s] only those who deserve killing." Conway, the series' writer at the time, saysthat "he had a purpose" and a "sense of honor. There was something behind his motivation that we didn't know….Something terrible had to turn this very straight-laced, rules-bound guy into the Punisher."

Later issues filled in his backstory. Castle received numerous medals for meritorious service in Vietnam, but his final tour went badly and the experience haunts him. He survived combat and returned home to Queens, only to see his wife and children murdered in Central Park after they accidentally witnessed a Mafia hit. When corrupt cops and courts fail to bring the killers to justice, Castle declares war on all criminals—from terrorists to muggers and everyone in between. "Frank Castle died with his family," he corrects a villain while pulling the trigger. "I'm the Punisher."

Initially planned as a one-off henchman type, Conway liked the Punisher so much that he brought him back as a recurring character. Audiences also responded positively, and he soon appeared in other characters' series as well. He did not get his own solo title until 1986, a dozen years after his debut. Writer Steven Grant said he had "been trying to get a Punisher series off the ground for years and no one [at Marvel] was interested." But Grant's five-issue Punisher limited series sold well and led to an ongoing comic the following year. That series ran for eight years and launched multiple spinoffs; from 1992 through 1995, three monthly Punisher titles were running concurrently.

Comic book heroes were traditionally inherently benevolent: Though they operated outside the law and spent much of their time beating criminals into submission, they usually refused to kill. The Punisher not only had no compunction about killing, but it was his singular purpose. Other comic heroes face many of the same villains again and again over their many decades in print; by definition, the Punisher's roster of recurring foes is rather short. Marvel senior editor Stephen Wacker said in 2011 that since debuting, Castle had killed 48,502 people.

His murderousness also puts him at odds with other heroes, who can see him as little better than the crooks and killers they encounter. As a result, he has battled fellow heroes such as Daredevil, Spider-Man, and Wolverine (and also, for some reason, Archie).

Cops Heart the Punisher

In 2017, Catlettsburg, Kentucky, Police Chief Cameron Logan commissioned vinyl decals for the department's cruisers: Punisher skulls that read "Blue Lives Matter."

"I consider it to be a 'warrior logo,'" Logan told local media. "That decal represents that we will take any means necessary to keep our community safe." Logan spoke as if he were commanding troops in a war zone, but Catlettsburg employed only eight full-time officers for a town of 2,500. According to the app Nextdoor, "Catlettsburg is considered a safe place to live," with violent and property crime rates below state and national averages. After a public backlash, Logan had the decals removed.

That same year, the Solvay, New York, Police Department drew criticism for similar decals. "The Punisher symbol on the patrol vehicles…is our way of showing our citizens that we will stand between good and evil," according to a statement credited in part to Solvay's police chief. "There is clearly a war on police and the criminal element attempting to infiltrate and destroy our communities, lifestyles and quality of living requiring men and women willing to stand up to evil and protect the good of society." (Solvay, a village of about 6,500, is "known for its clean streets and welcoming community," declared Nextdoor. At the time, its police department employed only 16 people, including the chief.)

Taken at face value, these police departments see themselves as under assault from unchecked criminal forces. In that mindset, the only way to survive is to treat the community like an occupied territory, seeing civilians as potential threats and displaying a decal that signals your willingness to use unconstrained violence.

Solvay's decals, in particular, featured a thin blue line in the skull design. As noted in Errol Morris' documentary of the same name, the phrase refers to the concept of "the 'thin blue line' of police that separate[s] the public from anarchy." While now ubiquitous, the design of a thin blue line on an American flag originated in 2014, three years before it was incorporated into Punisher skulls on police cars in Solvay.

In 2019, St. Louis barred 22 city police officers from submitting cases for prosecution after they were found to have posted racist content on social media. Ed Clark, president of the city's police union, published a letter on the union's Facebook page "asking all officers and supporters to adopt the Blue Line Punisher symbol as their profile symbol in a show of solidarity."

"The Blue Line symbol and the Blue Line Punisher symbol have been widely embraced by the law enforcement community as a symbol of the war against those who hate law enforcement," Clark added. "It's how we show the world that we hold the line between good and evil."

But it's more complicated than that.

"The thin blue line narrative…highlights the assumed differences between officers and citizens and further progresses an 'us versus them' mentality among officers," criminologists Don L. Kurtz and Alayna Colburn wrote in 2019.

Kurtz and Colburn found that the thin blue line narrative "relates to the idea that death surrounds officers as they go about their daily job," though statistically that's not necessarily true. As a result, the narrative "pushes a limited subset of society into seeking the profession—people that are more likely to be conservative, justify physical violence and deadly force, are distrustful of the community, and generally suspicious of those outside of law enforcement."

Now imagine what that same symbol signifies when paired with the skull logo of an extrajudicial murderer.

Why Police Adoration of the Punisher Matters

One could argue that police adopting the cartoonish logo of a fictional character is no big deal. Nobody would bat an eye at police officers with Superman patches. But the Punisher specifically contradicts what the police should represent.

"While tamer vigilantes complicate the job of law enforcement, they accept the legitimacy of the justice system and supplement rather than deconstruct the political order," Kent Worcester, a political scientist at Marymount Manhattan College, wrote in A Cultural History of the Punisher. "Frank Castle…operates under the assumption that the law itself is a fraud and a fiction."

All too often, an embrace of the character demonstrably coincides with a proclivity to abuse one's power. "Frank Castle does to bad guys and girls what we sometimes wish we could legally do," Jesse Murrieta, a security official who had worked in federal law enforcement, told Vulture in 2020. "Castle doesn't see shades of grey, which, unfortunately, the American justice system is littered with and which tends to slow down and sometimes even hinder victims of crime from getting the justice they deserve."

In 2004, numerous off-duty Milwaukee police officers accused Frank Jude Jr. of stealing a wallet and badge at a house party. Though they searched him and didn't find either, they then assaulted Jude so badly that an emergency room physician resorted to taking photos because "there were too many [injuries] to document" in writing.

Milwaukee Police Captain James Galezewski later discovered the officers involved in the assault belonged to a "clique" within the department who called themselves "the Punishers," who "wear black caps with a skull on them" and "get carried away" while on duty. "This is a group of rogue officers within our agency who I would characterize as brutal and abusive," Galezewski noted in a 2007 report.

In 2009, Sgt. Brent Raban of Florida's Palm Beach County Sheriff's Office repeatedly bragged on Facebook about beating suspects in the course of his work. He wore a skull cap with the word "punishment" on it. Raban told investigators he was inspired by comic book characters like the Punisher. He was demoted and reassigned, and he would be fired the following year. An arbitrator later ordered the department to reinstate Raban and pay him $150,000 in back pay.

As actor Bernthal alluded, the Punisher is also popular among members of the military. This makes sense, given Castle's status as a war hero and his overtly militaristic worldview. But it also fits another troubling aspect of the police/Punisher intersection.

The Punisher as Symbol of a Militarized Police

The 9/11 attacks inspired a patriotic and nationalistic fervor and ushered in an era of unchecked police militarization. Such militarization was already on the rise over the previous few decades, but 9/11 created an atmosphere in which no method of retaliation was off limits. In 2003, as a means of fighting terrorism, the Department of Homeland Security began dispensing military weapons and equipment to police departments throughout the country.

When protests broke out after a police shooting in Ferguson, Missouri, in August 2014, officers responded wearing camouflage, brandishing military surplus shotguns and M4 rifles, and driving armored vehicles designed to withstand mines and roadside bombs. In 2020, similar scenes took place across the country: As Black Lives Matter demonstrators protested police brutality, officers outfitted in combat gear deployed brutal and violent tactics to put down demonstrations that often warranted little or no force. Some protests did turn violent, marked by rioting and looting, but reports later found that across the country, police largely responded in excess of what the situation required—ironically validating many of the protesters' concerns.

As both the 2020 protests and the police response made international news, commenters noted the presence of Punisher skulls on officers' uniforms. Sadly, neither trend was new. A 75-second video uploaded to YouTube in 2009 depicts a police training exercise in Doraville, Georgia. In the video, several heavily armed SWAT officers pile out of an M113 armored personnel carrier—designed to safely transport up to 11 soldiers at a time to the front lines of a combat zone—with "Doraville Police Department SWAT" printed on the side. The video starts and ends with flashes of the Punisher skull, set to the industrial metal song "Die Motherfucker Die." The city didn't add these flourishes, but as Radley Balko wrote in 2014 in The Washington Post, "At least as of this writing, the video was posted on the front page of the Doraville Police Department Web site."

Doraville, a suburb of Atlanta with about 10,000 residents, has crime rates higher than the state and national averages. But most of that crime is property-related, hardly the kind that would require an armored vehicle. In emails exchanged after Balko's article, city officials chose to take the video down from the police department's website, and city manager Shawn Gillen noted, "We no longer own the tank." But the emails also showed the vehicle's primary usefulness was not in stopping or solving crime: A city councilmember asked if the city should create a "presentation" to "show how the tank has helped in the past, specifically during the ice storms."

"The Department of Defense's 1033 program, which offers free surplus military equipment to police departments, has transferred at least $1.6 billion worth of equipment to departments across the country since 9/11, compared to just $27 million before the attacks," Reason's C.J. Ciaramella wrote in 2021. That was in addition to another $24.3 billion in grants that city and state governments used to purchase additional military-style equipment.

"When controlling for other variables, counties who received the highest amount of military equipment through the 1033 Program recorded twice as many police killings than counties that did not receive any equipment," according to a 2020 article in the Georgetown Security Studies Review. "A report on Georgia law enforcement agencies discovered that participating police departments and sheriff offices who took in more than $1,000 in 1033 money, on average, had four times as many fatalities as non-participating agencies."

Given what the Punisher represents, and how police departments have militarized over the last few years, it's unfortunate but perhaps unsurprising that police have adopted the character's iconography as their own. Comics writers have increasingly contended with the Punisher's popularity among police—even adapting it into the pages of the comics. In a 1993 storyline, Castle travels to Baltimore to find and kill a major drug distributor. While there, he is stopped by two local cops—but instead of arresting him, they encourage him to finish the job and marvel at his freedom to operate with "no courts, no warrants, no rules." They even threaten him with reprisal if he doesn't kill his target. Castle bristles at doing the officers' bidding, even indirectly, but he decides that unless they're "dirty," they aren't his concern.

In a storyline from the early 2000s, the New York Police Department (NYPD) names its most ineffectual detective to head the Punisher task force, because the other detectives not so secretly prefer the Punisher's method of handling criminals to their own. Over time, as life began to imitate art, writers took a different approach, openly confronting whether cops should support Frank's mission. Matthew Rosenberg tackled the issue most directly when writing the character in 2018 and 2019. In one issue, NYPD officers argue over Castle's methods—whether he "does more to clean up the streets than we'll ever be allowed to" or if he's just "a frickin' Nazi."

Later in the same series, when two officers spot Castle on the street—blood on his gloves, still fresh from a recent kill—they get excited and try to take selfies. While most of the NYPD "want[s] you in the ground," they tell him, they belong to a small but vocal contingent who "believe in what you do" and sport his skull logo as a decal on their car.

Castle peels off the decal and rips it up. "We're not the same," he admonishes them. "You took an oath to uphold the law. You help people. I gave all that up a long time ago." When the officers protest that he "started something" and "showed how it's done," Castle replies, "If I find out you are trying to do what I do, I'll come for you next."

The Punisher as a Creature of His Time

As a longtime fan of the character who is uncomfortable with the way the police and military have co-opted him, I have to ask myself: What should he represent?

The Punisher was a product of his time. He debuted in February 1974, just five months before the theatrical release of Death Wish, in which Charles Bronson wages a one-man war on crime after a gang murders his wife and brutalizes his daughter. The film had so much prerelease hype that Paramount Pictures raised ticket prices for its premiere screening. Three years earlier, Clint Eastwood starred in Dirty Harry as a San Francisco detective willing to break any rule—including limitations on the use of force—to catch a killer. Each film would spawn four sequels.

Americans were concerned about crime, and for good reason. "Between 1960 and 1980, the homicide rate doubled, and the violent crime rate, as measured by police reports, more than tripled," according to Alex Tabarrok of the Mercatus Center at George Mason University. "The violence of the 1970s was also more impersonal than previous violence. Homicide rates doubled, but homicide rates by strangers increased much faster, especially in the big cities."

The same was true when the Punisher's first solo series debuted in January 1986. The previous year, "the number of crimes reported in the United States rose 5 percent," including "increases in all major categories of crime," The New York Times reported. "The numbers showed that violent crime, including murder and rape, was up 4 percent in 1985."

Just like Death Wish, Dirty Harry, and other revenge thrillers from the era, the Punisher reflected people's concerns about crime, meeting the senseless violence they feared with a brutally effective counterresponse. "I've heard people call me crazy, and maybe they're right. I can't judge something like that," Castle says in a 1975 issue. "I only know there's a war going on in this country between citizen and criminal—and the citizens are losing."

Marvel ended all Punisher series in 1995 amid declining sales throughout the industry—the company would file for bankruptcy the following year. When the Punisher returned in 2000, the U.S. looked very different than it had when the character debuted.

"Homicide rates plunged 43 percent from the peak in 1991 to 2001, reaching the lowest levels in 35 years," economist Steven Levitt wrote in 2004. The FBI's "violent and property crime indexes fell 34 and 29 percent, respectively, over that same period. These declines occurred essentially without warning: leading experts were predicting an explosion in crime in the early and mid-1990s, precisely the point when crime rates began to plunge."

That included Castle's home city: From 1990 through 1998, New York City's homicide rate plummeted, falling from 30.7 per 100,000 people to 8; the city hadn't seen a rate in the single digits since 1967. New York City, portrayed as a dystopia in films like Death Wish and The Warriors, was somehow becoming one of the safest cities in America.

The Punisher had thrived in an era of seemingly unchecked crime. What does a writer do with him when, statistically, Americans are safer than they've been in decades?

Garth Ennis is often named as one of the Punisher's greatest writers. He is credited with revitalizing the character's popularity in the 21st century, starting with the 2000 miniseries The Punisher: Welcome Back, Frank. While never shying away from the character's proclivity for violence, Ennis also depicted the mental and emotional toll Castle's experiences had on him.

Ennis "tended to write Castle as a man who was mentally destroyed during his service in Vietnam," Abraham Josephine Riesman wrote for Vulture in 2015, "and who has become a dangerous psychopath." Ennis' 21st century Punisher is not a badass hero or an avenging angel; he is a killer for the sake of killing. He is less ideological than pathological, a textbook case of PTSD. More broadly, he is a casualty of America's reckless warmaking abroad and its spiraling crime rates at home: Vietnam traumatized him, and the deaths of his family radicalized him to seek retributive violence.

Handling the character through the PTSD lens may be unsatisfying for those who look to Castle as a hero—or worse, as a role model. But it's perfectly in keeping with his history, and what has always made him work as a character. "The attraction to me back when I was creating the character was that complexity, that layer of semi-justification, but still [being] on the wrong side," Conway says. "It's a tough thing to unravel, but it's worth unraveling….It is complex, and the complexity is what we should be interested in."

Rethinking a Complex Legacy

People who should know better continue to pattern themselves after a comic book character who is definitively not to be emulated. In addition to cops and soldiers, the character has also proven popular among President Donald Trump's supporters and the paramilitary right—groups who want to convey strength over all else. Some of the rioters who stormed the U.S. Capitol on January 6, 2021, wore Punisher skulls. "These people are misguided, lost, and afraid. They have nothing to do with what Frank stands for or is about," Bernthal tweeted at the time.

After January 6, Mike Avila wrote in SYFY WIRE that perhaps Marvel should retire the character. Is there another option—one that doesn't mean giving up on the Punisher altogether? Conway thinks so. For the past few years, the Punisher's creator has spoken out against the character's misuse, including by police. In 2020, he raised over $75,000 for Black Lives Matter in Los Angeles, selling T-shirts with artists' designs of the Punisher skull with BLM symbology. But he isn't ready to give up on the character.

He points to a scene in the Disney+ series Daredevil: Born Again, where Castle directly confronts and repudiates police who have taken up his mantle, in a way that feels authentic to the character.

"You don't embrace his attitude, but you recognize it. You see it for what it is," Conway says. "This is a guy who is in terrible pain….And I think that's something that should be addressed. I think that's some way toward a healing of the readership or the viewership, and an introduction to the complexity of the character going forward. Don't be afraid of this guy as a publisher, or as a studio. He asks you to think, he asks you to feel. And that's a valuable thing to do. I think that's justification for keeping the character alive."

I agree the Punisher still serves a legitimate purpose—not as a role model, but as an examination of our own impulses, and our desire to do the right thing even if in the wrong way. "As long as there are innocents who need avenging, the Punisher will never die," Pepose's 2024 series says in its closing panel.

I still like the character. I'll keep reading his comics and watching him on TV and in movies. But perhaps the days of wearing the skull are behind me.

This article originally appeared in print under the headline "The Punisher Isn’t a Role Model."

Show Comments (88)