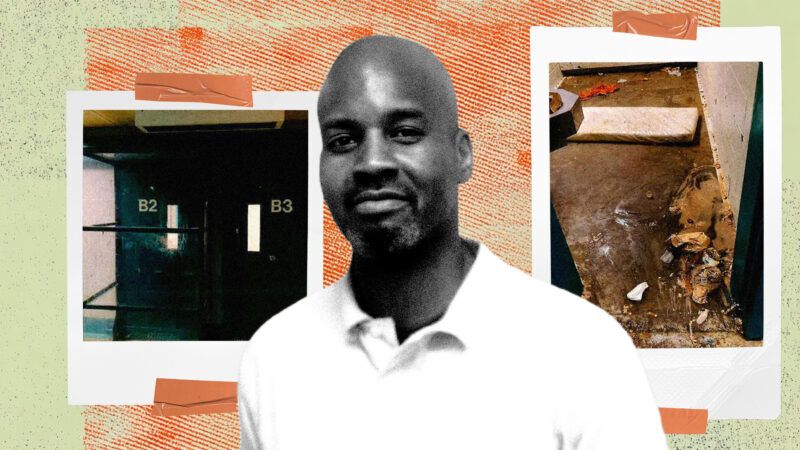

He Died of Thirst in Solitary Confinement. Now His Family Is Suing for Answers.

After 51-year-old Lamont Mealy was found dead in a Maryland prison cell, officials called it “natural causes.” His family’s lawsuit says guards intentionally shut off his water.

On December 22, 2022, 51-year-old Lamont Mealy was found guilty of the first-degree murder of his roommate and was sentenced to serve life in prison at the Western Correctional Institution in Cumberland, Maryland. A little more than six months later, he was found dead in his cell. Now, his sister, LaShawn Tyler, is suing the state, accusing prison staff of deliberate neglect and withholding records that could reveal how Mealy's death happened.

According to a complaint filed in the Baltimore County Circuit Court, Mealy, who had a history of mental illness, was placed in cuffs, chains, and a suicide-prevention vest and taken to solitary confinement "on or about" June 30, 2023. After placing him there, two officers—neither of whom was wearing name tags or displaying rank insignia—inexplicitly shut off the water to the cell.

Around July 2, the same two officers returned to the outside of the cell to taunt Mealy, asking him, "Are you thirsty?" Mealy repeatedly begged them for water but was never given any. The filing also asserts that he was denied several meals and that his condition rapidly deteriorated over the course of the next several days.

On or around the morning of July 5, a lieutenant warden allegedly stood in front of Mealy's cell, "but took no action," according to the complaint. From roughly 10 a.m. to 3 p.m. that day, the required welfare checks—meant to occur every half hour in Mealy's ward—were not performed. It wasn't until approximately 3 p.m. that the lieutenant warden ordered a sergeant to "pull the man out of there." Staff then dragged Mealy's fresh corpse out on a blanket; no medical staff were called prior to the removal, the filing attests.

Initially, the prison informed Mealy's family that he died of "natural causes," Kristen Mack, the plaintiff's attorney, tells Reason. However, Danny Hoskins, another prisoner who was being held in solitary confinement in a cell adjacent to Mealy's, claims he saw what really happened.

Shortly after the death, Hoskins asked to speak privately with prison officials about what he had seen. According to the complaint, Hoskins was met with bureaucratic stonewalling, physical assault from corrections officers, and warnings to mind his own business. He was eventually transferred to another prison, where he filed an Administrative Remedy Procedure request—Maryland's internal grievance system for reporting abuse. In it, Hoskins described the water shutoff and Mealy's death. Afterward, he sent letters to the warden, the secretary of the Department of Public Safety and Correctional Services, and Democratic Gov. Wes Moore, but never received a response. In June of this year, Hoskin's post-conviction attorney reached out to Mack about the incident.

Mack subsequently submitted a Freedom of Information Act request to the state's Department of Public Safety and Correctional Services on or around June 5, requesting access to all written and electronic records—which included housing and classification records, tier logbooks, photographs, security footage, and medical records—surrounding Mealy's confinement and death. While the department agreed to produce some of this material, they refused to release a requested internal affairs report, with the state's principal counsel, Stuart Nathan, claiming that it was "quite voluminous" and that he would "need to review and determine if there is any need for any redactions" before releasing it publicly.

"The State is [still] doing everything that it can to avoid producing records that we know exist and that we are entitled to have," Mack says. "They have attempted to obstruct any and all efforts made to uncover the truth."

However, after several follow-up emails in August yielded no report or even a response, Tyler sued the state and the Department of Corrections for missing Maryland's one-month statutory deadline for public records requests, and for failing to provide a legally sufficient explanation for withholding the internal investigation. Tyler is seeking a court order compelling the release of the full investigation and all related records. A hearing is scheduled for January 2026.

Sadly, deaths like Mealy's are not uncommon. "The reality is horrific things like this happen all the time in prisons," Mack says, "and the public only hears about it if—and only if—information about what happened reaches the right set of ears."

The court's decision will determine how much the family—and the public—will ever know about what happened inside Mealy's cell in his final week, and whether anyone will be held accountable for a man dying of thirst behind bars.

*CORRECTION: This article originally misstated the amount of time between Lamont Mealy's conviction and his death.

Show Comments (37)