The Federal Reserve Cuts Rates With Inflation Still Hot. Is Political Pressure Winning?

When the Federal Reserve is concerned about inflation, it increases the federal funds rate. Despite expressing such concerns, the Fed lowered it.

The Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) announced Wednesday that the Federal Reserve would lower its federal funds rate target—the interest rate that banks charge each other to borrow overnight—by 0.25 percentage points. The decision, which has been expected for weeks, may lower interest rates for mortgages, other loans, and savings accounts, but it could come at the expense of an elevated cost of living.

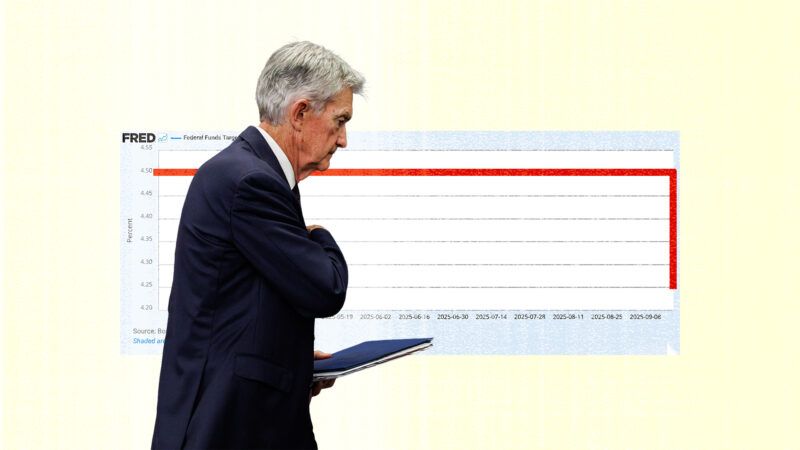

Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell voted to lower the fed funds target range between 4.0 percent and 4.25 percent alongside 10 members of the 12-person FOMC. Stephen Miran, nominated by President Donald Trump to be a member of the Board of Governors on September 2 and confirmed by the Senate on Monday, was the sole member who dissented. Miran "preferred to lower the target range for the federal funds rate by 1/2 percentage point at this meeting," per the Fed's statement.

Miran's preference for a lower rate than the rest of the FOMC comes as no surprise; Trump has been pressuring the Fed to lower rates since February. In a June letter, in which the president referred to Powell as "too late," Trump indicated that the U.S. should be paying "1% Interest, or better!" (The last time the federal funds rate upper limit was 1 percent was May 2022, when the U.S. was still recovering from pandemic-era lockdowns.) Powell earned this moniker in July, when the FOMC held the fed funds rate between 4.25 percent and 4.50 percent, where it has been since December 2024 in a bid to bring year-over-year inflation down from 2.6 percent.

Inflation, as measured by the Fed's preferred price index, remained at 2.6 percent in July, the most recent month in which data are available. The Fed's target is 2 percent. Moreover, in August, the consumer price index, which the Bureau of Labor Statistics uses to measure inflation, increased by 0.4 percent—the greatest monthly increase in inflation since January.

At the time of the last FOMC meeting in July, Reason spoke to Peter C. Earle, director of economics and economic freedom at the American Institute for Economic Research, who said the Fed's decision not to lower rates reflected both inflation vigilance and strategic positioning, affording it "room to maneuver should a tariff-induced shock…suddenly materialize." Earle is less rosy about the Fed's most recent decision, which he says is "less an act of prudence than of expedience—an effort either to placate political pressure from the White House or to indulge a reflexive bias toward intervention."

Although the Fed is charged with keeping unemployment low, and average monthly jobs growth is down to 75,000 from 186,000 jobs per month in 2024, the unemployment rate has held steady around 4.2 percent since January. Earle says that "a measurable rise in unemployment of two to three tenths of a percentage point would strengthen the case [for the rate change]." Since that has not been observed—unemployment peaked at 4.3 percent in August, "the most likely outcome is…a temporary lift to asset markets accompanied by renewed upward pressure on consumer prices."

The FOMC acknowledged in its own announcement that "inflation has moved up and remains somewhat elevated" while the unemployment rate "remains low." Increasing the fed funds rate is one of the Fed's primary tools to combat inflationary pressures; lowering it is the opposite of what the Fed should do if it's seriously concerned about inflation. Apparently, it's not.

Show Comments (21)