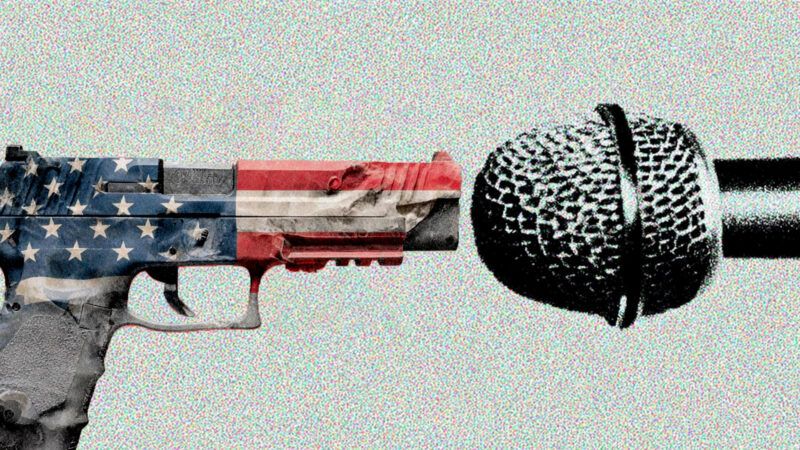

The ACLU Says a New York Official Violated the NRA's First Amendment Rights. They Still Can't Sue Her.

A federal court concluded the official was entitled to qualified immunity in a case that united two unlikely allies.

The national debate over qualified immunity—the legal doctrine that can make it difficult to sue government officials for constitutional violations—has largely focused on police misconduct.

But it also broadly applies to state and local government employees. A recent federal court ruling is a reminder of that, uniting two unlikely bedfellows: the National Rifle Association (NRA) and the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU).

The legal odyssey stretches back to 2017, when the New York Department of Financial Services (DFS) found that Carry Guard—a self-defense insurance program endorsed by the NRA and underwritten by insurance companies—had violated state insurance law by offering coverage for criminally negligent acts with a firearm that killed or injured another person. Those insurance companies ultimately paid civil penalties.

The 2018 shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida, which occurred a few months after that probe, subsequently prompted Maria Vullo—then a superintendent at DFS—to weaponize her position to cripple the gun organization's advocacy and hamstring its access to insurance companies and financial institutions, the NRA alleges.

Specifically, the group says Vullo expressed in private meetings with insurance providers that she would selectively apply enforcement actions to those who insisted on doing business with the NRA. She also issued two memos to insurers and banks titled "Guidance on Risk Management Relating to the NRA and Similar Gun Promotion Organizations," in which she encouraged them to "continue evaluating and managing their risks, including reputational risks, that may arise from their dealings with the NRA or similar gun promotion organizations"; to "review any relationships they have with the NRA or similar gun promotion organizations"; and to "take prompt actions to manag[e] these risks and promote public health and safety."

When the gun advocacy group first sued, alleging Vullo had violated its First Amendment rights, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 2nd Circuit rejected that assertion. Vullo had not infringed on the NRA's free speech protections, the court said. The group's appeal eventually made it to the Supreme Court—which unanimously ruled in May 2024 that the NRA had, in fact, stated a viable First Amendment claim. "Government officials cannot attempt to coerce private parties in order to punish or suppress views that the government disfavors," wrote Justice Sonia Sotomayor. The NRA, which was represented by the ACLU, "plausibly alleges that respondent Maria Vullo did just that." The ruling sent the case back to the lower court.

In a decision published this month, the 2nd Circuit applied the Supreme Court's guidance, accepting that Vullo allegedly violated the First Amendment. But it still concluded the NRA cannot move forward with its lawsuit, ultimately ruling that Vullo did not have clear enough notice that such actions would run afoul of the Constitution.

"Although the NRA plausibly alleged a First Amendment claim, we conclude that Vullo is entitled to qualified immunity because the First Amendment rights asserted were not clearly established at the time of the challenged conduct," wrote Judge Denny Chin for the 2nd Circuit. "True, the cases cited above clearly established that coercion amounting to censorship and retaliation violate the First Amendment as a general matter, but they did not sufficiently define the contours of that right such that it would have been clear to every reasonable official in 2017 or 2018 that Vullo's conduct with respect to a third party—not a speaker or a speaker's conduit—violated that right."

Core to the decision, and to the doctrine itself, is the idea that government officials can't be held liable in civil court for constitutional violations unless the alleged misconduct has already been outlined in near-exact detail and ruled unconstitutional in a prior court precedent, thereby putting them on notice. It assumes, for one, that state and local employees are reading case law for training, which is dubious. But it also deprives victims of the mere opportunity to ask a jury if damages are merited.

It is possible here that they are not. An alleged participant in one private meeting with Vullo, for instance, denies the conversation took place. There is no way to answer the broader question with confidence, however, if public officials are immune from facing fact finders.

Show Comments (31)