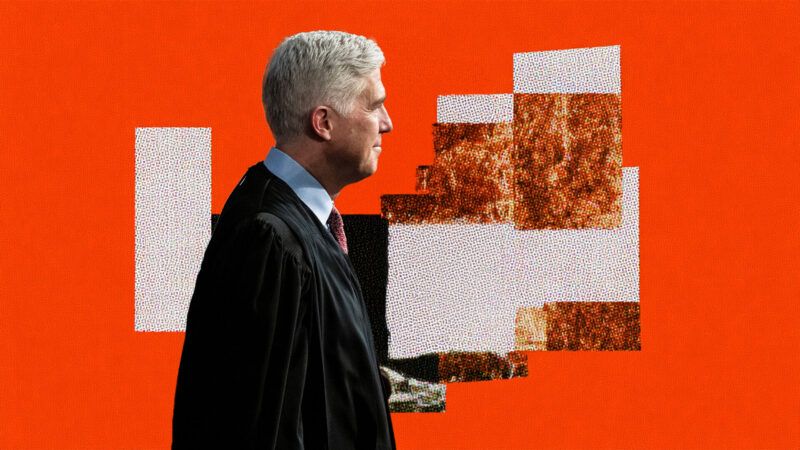

What Neil Gorsuch Gets Wrong About Judges and Government Power

Plus: Ozzy Osbourne, RIP.

As the author of a book called Overruled: The Long War for Control of the U.S. Supreme Court, I naturally took an interest when Supreme Court Justice Neil Gorsuch published a book late last year called Over Ruled: The Human Toll of Too Much Law. But life moves pretty fast sometimes, and I didn't get around to reading Gorsuch's book (co-written with his former law clerk Janie Nitze) until earlier this year. Then, to my surprise, I found Over Ruled to be extremely disappointing.

Allow me to explain why.

You’re reading Injustice System from Damon Root and Reason. Get more of Damon’s commentary on constitutional law and American history.

Gorsuch's book persuasively argues that "too much law" has harmed the American people. "When law expands rapidly in size and complexity," he writes, "when important rules can change (and change back again) with ease and little warning, when important guidance is sometimes found only in an official's desk drawer, who are the winners and losers?"

Take the issue of occupational licensing, an area of law that has vastly expanded in recent years. Many licensing laws serve no legitimate health or safety purpose. Yet the failure to follow such unnecessary laws nonetheless carries a costly penalty. In some cases, the punishment can be ruinous.

That was nearly the experience of Ashish Patel, an Indian immigrant living in Texas who wanted to work in the traditional craft of eyebrow threading. The problem for Patel was that Texas had labeled eyebrow threading as "cosmetology" and required would-be threaders to spend thousands of dollars and hundreds of hours obtaining a cosmetology license. Adding insult to injury, none of the 750 hours of state-mandated cosmetology classes even dealt with eyebrow threading.

And what is eyebrow threading? Simply this: Passing a loop of cotton thread over the eyebrows to remove unwanted hairs. No chemicals. No sharp objects. We're not talking about unlicensed brain surgery here.

Patel and several others, represented by the ace lawyers at the Institute for Justice, filed suit against the licensing scheme and ultimately prevailed before the Texas Supreme Court. Their legal efforts vindicated the liberty to work in a safe occupation without first obtaining the government's pointless and expensive approval.

Gorsuch discusses that case, Patel v. Texas Department of Licensing and Regulation, in Over Ruled. The threaders "banded together and brought suit against the state," he writes, "contending that its licensing scheme violated their right under the Texas Constitution 'to earn an honest living in the occupation of one's choice free from unreasonable government interference.' After early losses and years of litigation, the Texas Supreme Court took up their case and agreed with them."

That description is accurate as far as it goes. But Gorsuch also leaves out some crucial details.

In a concurring opinion filed in the case, Texas Supreme Court Justice Don Willett observed that it was a good thing for Patel that the matter was judged by a Texas court under the Texas Constitution. That's because the same case judged under "the federal Constitution as interpreted by federal courts" would have likely upheld the absurd licensing scheme. "Federal-style deference in economic matters," Willett noted, would have probably spelled legal doom for Patel and his fellow threaders.

What is "federal-style deference in economic matters"? Here is how the Supreme Court defined it in the far-reaching 1938 case of United States v. Carolene Products Co. When "regulatory legislation affecting ordinary commercial transactions" comes before the courts, the Supreme Court declared in Carolene Products, "the existence of facts supporting the legislative judgment is to be presumed." Translation: Judges are supposed to give lawmakers the benefit of the doubt and uphold the vast majority of economic regulations.

Fortunately for Patel, his "case arises under the Texas Constitution, over which we have final interpretive authority," Willett wrote, "and nothing in its 60,000-plus words requires judges to turn a blind eye to transparent rent-seeking that bends government power to private gain, thus robbing people of their innate right—antecedent to government—to earn an honest living. Indeed, even if the Texas Due Course of Law Clause mirrored perfectly the federal Due Process Clause," Willett added, "that in no way binds Texas courts to cut-and-paste federal rational-basis jurisprudence."

(In the interests of full disclosure, let me stop here to note that Willett favorably cited my book Overruled in his Patel opinion.)

Willett also made it clear in Patel that he viewed "federal-style deference in economic matters" with pronounced disfavor. "If judicial review means anything, it is that judicial restraint does not allow everything," Willett wrote. "Threaders with no license are less menacing than government with unlimited license."

Which brings us back to Gorsuch.

A key reason why we have "too much law" in this country—including too many arbitrary and unnecessary laws like the one at issue in Patel—is because the federal courts, acting in the name of judicial deference, have repeatedly refused to do anything about it. Rather than scrutinizing all such laws and striking down the malefactors, the federal courts routinely tip the scales in favor of lawmakers and regulators. And they do so in direct accordance with the Supreme Court's 1938 edict that "the existence of facts supporting the legislative judgment is to be presumed."

In other words, many Americans have little or no meaningful redress against "too much law" precisely because the doors of the federal courthouse have been effectively slammed shut in their faces.

Yet Gorsuch says nothing about any of that in Over Ruled. He discusses neither Carolene Products nor any of the other SCOTUS precedents which mandate "federal-style deference in economic matters."

What gives?

One possible answer is that Gorsuch disagrees with Willett about the proper role of the federal courts in such cases. If so, Gorsuch would certainly not be alone. Judicial deference has long been a rallying cry among a certain school of judicial conservatism, exemplified by influential figures including the late federal judge Robert Bork.

Does Gorsuch prefer the Bork school over the Willett school? Alas, we don't know because Gorsuch doesn't say. We're left to guess about which side he might be on.

What makes that silence so especially vexing is the fact that Gorsuch remains silent in a book specifically devoted to the very issues which have divided the two schools of judicial thought. His silence here feels a bit like a dodge.

So, while Over Ruled is well-written and engaging, it must be judged a disappointment. Gorsuch succeeds in drawing attention to an urgent problem, but he fails to reckon with the major role that his own court has played in making that problem even worse.

Odds & Ends: Ozzy Osbourne, RIP

I'm old enough to remember when the heavy metal icon Ozzy Osbourne, who died this week at the age of 76, was not celebrated as America's favorite bumbling reality TV dad, but rather was despised by many as an unholy threat to the social order. At my middle school in the late 1980s, simply wearing an Ozzy T-shirt to class was sufficient cause for some teachers to send you to the principal's office for the supposed crime of "promoting Satanism." Of course, that sort of censorial freakout by the powers-that-be only made me and my friends love the "Prince of Darkness" even more.

Thanks for the music, Ozzy, and for the memories. RIP.

Show Comments (24)