New Jersey Town Says Small Setbacks, Stray Cats Allow It To Seize Private Property

Two business owners say the city of Perth Amboy is using exceedingly flimsy blight allegations to take, and potentially demolish, their property.

Honey Meerzon's parents are Jews from the Soviet Union, who moved to the United States in the 1970s to escape religious discrimination. Luis Romero's parents fled Castro's Cuba when he was eight years old.

The two ended up as neighboring business owners at the corner of Smith and Herbert Streets in Perth Amboy, New Jersey. It's there that Romero has been running his family's tire shop, Quick Tire, for the past 20 years. Meerzon has owned the four-unit rental property next door for the past ten.

Now, these two children of refugees from communism are having their businesses taken from them by the all-too-American process of eminent domain.

Last month, the city council of Perth Amboy voted that Meerzon's and Romero's properties were not, in fact, comfortable homes or a successful business, but are rather blighted hazards.

Because their two buildings are too close together, too close to the street, and have some (since-collected) litter and stray cats in the backyard, the city says it is now entitled to take the properties.

Meerzon and Romero strongly object to the idea that their properties are in any way blighted. They argue that the city's report claiming otherwise is riddled with erroneous complaints and fatal factual errors.

Nevertheless, the city has moved forward with seizing their properties, which sit right on the edge of a massive city-facilitated warehouse project.

Both property owners now face a looming deadline at the end of May to file a lawsuit challenging the seizure.

"They refuse to answer our calls. They refuse to answer any of our lawyers," says Meerzon. "They're waiting for us to go to superior court to monetarily drain us until we have no choice but to take whatever they offer us."

Neither Perth Amboy's mayor nor any members of the city council responded to Reason's request for comment.

Both Meerzon and Romero see a dark irony in their properties being seized by the city, given their family's backgrounds.

"[My parents] said this is the only way you get on your feet. You have to take a risk, you have to make an investment, you have to leave a legacy for your children," Meerzon tells Reason. "This is what happens to the legacy they dreamt of having coming here."

"The reason [my parents] left Cuba is the system how it was, they just come to your home, say 'we want this property. You have to get out,'" says Romero. "Here it's done legally."

'Make Way for Gateway!'

In April 2024, Perth Amboy Mayor Helmin Caba and members of the city council gathered a few houses down from Meerzon's and Romero's properties on Smith Street for a little demolition work.

The occasion was a press conference to announce the beginning of the city's "Gateway" redevelopment project.

For two decades, Perth Amboy has been plotting a conversion of the town's waterfront and former industrial areas into a more desirable mix of apartments, recreational space, and logistics businesses.

Gateway, a joint project between the city's redevelopment agency and Denver-based developer Viridian Partners, was the latest stage in this massive, government-led reinvention of Perth Amboy.

Viridian Partners had promised to invest $110 million in cleaning up the 44-acre Gateway site that would eventually become a massive warehouse and parkland.

But first, some old buildings on the edge of the site had to be torn down.

"This key entrance to our city, once tarnished by decay, is now the focal point of our redevelopment efforts," the mayor said at the press conference, where he donned a hard hat and sat in a large excavator.

Enabling Perth Amboy to do the Gateway project is New Jersey's Local Redevelopment and Housing Law. The law allows local governments to create "redevelopment areas," inside of which they can deploy extraordinary carrots and sticks to attract and guide investment.

"In a redevelopment plan, a municipality can do a lot of stuff you can't normally do," says Peter Steck, a former New Jersey city planner and current planning consultant.

On the carrot side, redevelopment lets local governments offer hand-picked developers tax and financing incentives to build projects in which the city can play a major role in designing—down to the aesthetics and the building materials used.

"They like to play favorites, they can pick their designated developers and there is no required criteria of choice," says Steck.

On the stick side, local governments can seize properties within a redevelopment area and transfer them to their private development partners.

Officially, Meerzon and Romero shouldn't have had to worry that the excavator Caba had posed for photos on would come for their properties too.

City maps of the Gateway redevelopment area show that their little corner of Smith Street are excluded from the zone.

Moreover, New Jersey state law provides a number of procedural and substantive safeguards against local governments just willy-nilly seizing property for redevelopment.

Before a property can be taken, a local government must conduct a redevelopment study showing that the area is "in need of redevelopment." Generally that means that the properties in the area are disused, blighted, or pose a health or safety hazard.

That study has to be approved by votes from both a local planning agency and a governing body, like a city council. Property owners are given an opportunity to contest any blight allegations at public hearings before those bodies.

"New Jersey law on its face is supposed to only allow New Jersey municipalities to declare land blighted if it's causing actual harm to the surrounding properties," says Robert McNamara, an attorney with the Institute for Justice who has litigated redevelopment seizures in New Jersey.

Yet those theoretically robust protections are often a lot weaker in practice. Given the powers New Jersey's redevelopment law unlocks, municipalities have a lot of incentive to see blight that isn't there.

Once a redevelopment study is initiated, "the predisposition is that the area is blighted," says Steck. "The planner doing the investigation is programmed to find whatever he or she can to fit within the criteria and tell the planning board, 'In my opinion, it's blighted.'"

Though Meerzon and Romero didn't know it, by the time of that April 2024 press conference down the road, Perth Amboy was already months into a redevelopment study of their properties.

It would conclude that Meerzon's occupied apartment building and Romero's tire shop were both just as blighted as the vacant, boarded up homes being torn down a few houses down.

The Taking

In December 2024, Meerzon received a notice in the mail from an attorney working for the city referencing a redevelopment study that had been conducted on her property and the neighboring ones. It said that a Zoom call to discuss the study was scheduled in two days.

At the time, Meerzon hadn't received a copy of the referenced study. When she called the city to get one, she says the staff were initially unforthcoming.

"They said the woman who can give me the report is on vacation for a week and cannot help me," says Meerzon.

With a call with the city scheduled in two days, Meerzon went to city hall and said she wouldn't leave until she was provided a copy of the report.

That did the trick. That same day, the city turned over an 87-page report detailing how Meerzon's and Romero's properties were blighted, unsafe, and therefore qualifying for a redevelopment seizure.

The blight designation was shocking to Meerzon. Since acquiring her property, she'd invested some $150,00 in upgrades: adding new siding, replacing boilers, installing a French drain, and adding a new fire alarm system at the city's request.

Indeed, the city's evidence that her property, as well as her neighbor's, was blighted seemed thin.

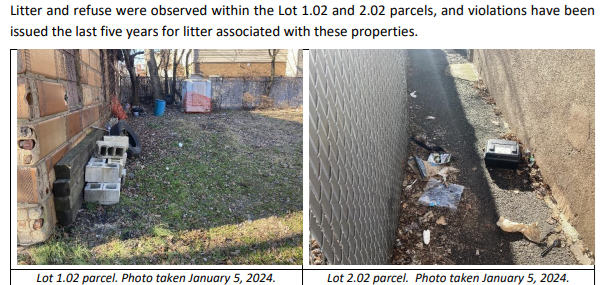

The redevelopment study cited a handful of traffic stops in front of the properties and some trash and stray cats behind them as evidence that they had become "detrimental to the safety, health, morals, or welfare of the community."

The study claimed that both buildings' lack of setbacks from the street posed a safety hazard. Meerzon's building was also described as having too little parking and receiving too many Fire Department calls.

The study also said that Romero's and Meerzon's buildings were blocking two small, vacant city-owned parcels behind them. That made those parcels unlikely to be developed—and New Jersey's redevelopment law allows property seizures to facilitate development on otherwise undevelopable lots.

None of these allegations made much sense to Romero or Meerzon.

Two of the five Fire Department visits to Meerzon's property cited in the city's report were medical responses to one of her tenants reporting a respiratory issue.

The building's close distance from the street was a common feature of properties in the area. No one had raised concerns about it before.

"We never had any issues with the city, any code enforcement, violations, safety issues, accidents, nothing. No pedestrians complaining about vehicles coming out," says Romero.

With it increasingly clear that the city was determined to seize their properties, Meerzon and Romero jointly hired an attorney. They also brought on Steck, the planner, to prepare a report rebutting the city's evidence that their properties qualified for redevelopment.

Steck's report details a number of apparent errors in the city's redevelopment study. The most glaring mistake was that they appear to have gotten the property lines wrong.

As can be seen in the below image, the city's report shows the front of Meerzon's and Romero's buildings as extending several feet beyond the property line into the public right of way. That property line placement also shows their properties covering vacant land behind them.

Steck's report argues this property line is "obviously misplaced." Using satellite photos from the state's Department of Environmental Protection, he shows that their properties end at the street in the front and do not cover the vacant land behind them.

This more logical placement of the property lines undermines several of the city's determinations that the properties qualify for redevelopment.

The vacant lots that Romero's and Meerzon's properties are allegedly blocking, and therefore rendering undevelopable, are instead owned by Romero himself and used as tire shed for his business. The litter said to be in the rear of the properties is actually on adjacent city-owned land.

"They were saying in the back of the property there's trash and wild cats going around. But that property isn't even in the study area and that's embarrassing," says Steck.

'Don't Bulldoze Our Dreams'

At the beginning of the year, Meerzon and Romero had that Zoom call with a city planning board attorney confirming that Perth Amboy was in fact interested in seizing their properties for redevelopment.

The next required step was a hearing before the city's planning board, which happened in March 2025.

At the hearing, Meerzon and Romero presented evidence to the city planning board showing that their properties were not blighted.

They argued that the litter the city complained about in their report was either not on their properties or had already been cleared. Either way, it was a de minimis amount of refuse.

Meerzon says that at that hearing, the city focused blight accusations on how close her and Romero's buildings were to the street (which was allegedly a traffic hazard) and how close they were to each other (which was allegedly a fire hazard).

If these features justified the seizure of Romero's and Meerzon's properties, then many other properties in Perth Amboy also meet the definition of blight.

"To conclude that a residential vehicle backing out on a busy road in Perth Amboy is a basis for an area in need of redevelopment designation likely renders hundreds of homes in the City as eligible for a blight designation," reads Steck's report.

Ultimately, this did nothing to move the planning board, which voted to approve the redevelopment designation.

The final step in the process was a city council hearing and vote, which was held in mid-April.

NJ.com reported that some 80 people attended the hearing to oppose the seizure, sporting signs that read "Don't bulldoze our dreams" and "Save our homes, save our family."

About a dozen people spoke at the meeting, all in support of Meerzon and Romero. No members of the public supported the city's efforts to take the property.

At the hearing, Romero told the city council there was nowhere else in the city where he could relocate his tire shop, meaning his employees (several of whom had worked at the tire shop for decades) would lose their jobs.

Meerzon said she wasn't trying to stand in the way of the area's growth. "We are not against development. But we are against being erased," she said, per NJ.com.

After receiving this public testimony, the five-member Perth Amboy city council went into a closed session to discuss the seizure of Meerzon's and Romero's properties.

They ended up spending three hours deliberating. One by one, Meerzon's and Romero's supporters slowly started to trickle out of city hall.

Finally, near midnight, the city council returned and, without any public discussion, voted 4–1 to declare the two properties in need of redevelopment, and thus, subject to seizure.

Next Steps

With the redevelopment vote complete, Meerzon's and Romero's properties are now subject to seizure effectively at the city's discretion.

Their only remaining option to save their properties is to proactively sue the city in a local superior court. State law gives them until the end of May to file a lawsuit.

Hoping to avoid an expensive legal fight, Meerzon and Romero have both been trying to negotiate with the city about improvements they can make on their property. The city, they say, has been completely unresponsive.

The city doesn't even have to communicate exactly what the property will be used for. Since the purpose of the seizure is to clear blight, and that's a public purpose, effectively the seizure is the public use.

"I can do whatever they tell me to do," Meerzon tells Reason. "We tried calling them to see what we can do, if we can negotiate something, if we can talk about anything. Nobody will call us back."

The taking of her property would not only be a major financial loss for her but also a serious hardship for her tenants.

"They are tenants who walk to work. They don't have cars. Displacing them is a huge, huge hit because they have no way to get to work now," she says.

Meerzon notes that their properties have always been excluded from the Gateway redevelopment area and should be left alone as a consequence.

However, it's not an unusual tactic for cities to leave areas that they intend to bulldoze out of a major redevelopment area. This way, if a property owner does challenge a seizure in court, the rest of the project isn't held up as well.

New Jersey's courts have prevented redevelopment seizures in the past.

McNamara, the Institute for Justice attorney, successfully litigated a case challenging the state Casino Reinvestment Development Authority's attempted seizure of an Atlantic City man's home. That case was resolved in 2019.

"What Perth Amboy is hoping for is that they'll get away with declaring land blighted when in fact the land is simply coveted," says McNamara.

Rent Free is a weekly newsletter from Christian Britschgi on urbanism and the fight for less regulation, more housing, more property rights, and more freedom in America's cities.

Show Comments (41)