Are We Still Living in 1999?

A new book argues that late-20th-century lowbrow culture created the modern world.

1999: The Year Low Culture Conquered America and Kickstarted Our Bizarre Times, by Ross Benes, University Press of Kansas, 296 pages, $32.99

In 1982, Prince first sang that he planned to party "like it's 1999." But on New Year's Eve of 1998, as MTV counted down to the actual year 1999, it wasn't the Purple One who performed that song in Times Square. As Ross Benes notes in his new book 1999: The Year Low Culture Conquered America and Kickstarted Our Bizarre Times, it was the nu metal band Limp Bizkit that performed one of the 20th century's most recognizable dance hits, swapping the original's synths and funky basslines for chugging guitars and hip-hop breakbeats.

In retrospect, Benes writes, this signaled more than just a programming decision: For Limp Bizkit—"proud sellouts who halfway rap and halfway rock about boning"—to appear on "the youth station as the clocks turned over demonstrated low culture's domination."

While not perfect—and weakest when defending its titular premise—Benes' book makes a compelling case that the most reviled, lowbrow forms of popular entertainment were instrumental in creating many things we enjoy today, and that they also offered an effective remedy for the things we hate.

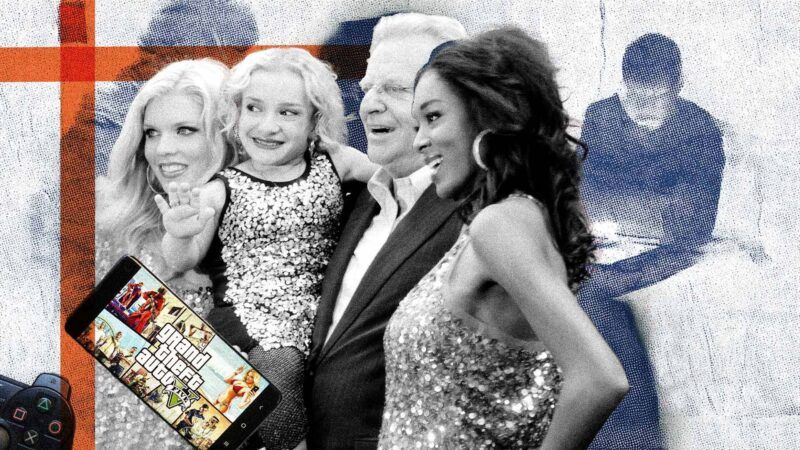

"Low culture" is defined as popular culture that is less sophisticated and more mainstream, intended to appeal to a broad audience. Benes cites multiple examples, among them video games, Beanie Babies, internet porn, and Jerry Springer; none originated in 1999, but Benes argues that was when they reached their cultural zenith.

In part, this was the result of an increasingly diverse media landscape that allowed ideas to spread more easily, thanks both to advances in technology and a lighter hand from government regulators.

"Consider the interconnectedness of 1990s mass media," Benes writes. "During the late nineties, print circulation held steady, cable TV added channels and gained subscribers, and the internet emerged. This happened while media conglomerates gobbled up more companies and became increasingly deregulated. The result was a media environment that extended the reach of trashy stories and entertainment through heavy cross-promotion."

The book isn't a jeremiad. "While my thesis is that 1999 was the year low culture took over the world, I'm not arguing that its pop culture was uniformly trash," he writes. In fact, 1999 saw the premieres of numerous respected cultural achievements, including such films as Magnolia and Office Space and such TV shows as The Sopranos. But "despite this revered entertainment, low culture was plenty in-demand. And these lowbrow products teach us most about the world." In fact, the year's most honored film at the Oscars, American Beauty—winning five prizes, including Best Picture, Best Director, and Best Actor—was itself partly based on the story of Joey Buttafuoco, the Long Island mechanic whose teenaged paramour shot his wife in 1992, yielding tabloid fodder for years to come.

Jerry Springer's eponymous talk show was the apotheosis of trash TV. The show reveled in the lurid and distasteful. An episode's guests might be siblings who were dating the same person—or each other. Salacious details once only whispered about were now syndicated on weekday afternoons. Segments routinely turned into fistfights, with the live audience whooping and hollering like they were watching professional wrestling (which also got more popular in the late 1990s and gets its own chapter in the book).

Benes uses Springer's show to demonstrate the '90s trend toward lowbrow, cheaply produced content that eventually led to the explosion of reality shows in the 2000s—which themselves helped shape the world we know today. Broadcast networks' ratings fell as cable TV and VCRs encroached on their home entertainment oligopoly. (Benes notes in the epilogue that movie studios and broadcasters petitioned the government to limit VCRs and cable. While VCRs survived a court challenge, cable was effectively locked out of most major markets for decades until federal deregulation in the 1970s.) Deregulation then allowed networks to license their own shows for syndication. Where Jerry Springer and shows of its ilk were produced for cheap by syndicators and sold for broadcast at huge markups, the networks could now get in on the action—creating their own cheap content that was immediately profitable and could then be syndicated for more profits.

ABC developed the primetime quiz show Who Wants To Be a Millionaire specifically because it would cost less than a scripted program. It was an immediate hit when it premiered in August 1999, becoming the year's most watched series. That same year, CBS merged with Viacom as soon as the government allowed such mergers (another bit of deregulation). CBS was now a sister station to MTV, which had expanded into reality programming with The Real World, the original "seven strangers in a house" show.

"Viacom and CBS went all-in on reality because doing so was cheap, effective, and fit in with the company's efforts to reduce production costs," Benes writes. Huge successes such as Survivor, Big Brother, and The Amazing Race followed, each of which still airs new episodes today. Soon reality shows were everywhere.

We very much still live in that world. Perhaps the most famous reality TV personality of all time is Donald Trump, whose competition series The Apprentice premiered in 2004 and turned him from a boorish Manhattan has-been into an international symbol of wealth and success—an image central to his 2016 run for the presidency. As improbable as that trajectory is, Benes makes it clear that it wasn't unforeseeable. In 1998, newspaper columnist Art Buchwald reflected on the decade's political scandals—chiefly, then-President Bill Clinton's dalliances with a young White House intern—writing, "Washington is getting more like Jerry Springer, or, worse still, Jerry Springer is getting more like Washington."

"The thing that annoys me about Trump is that he took my show and brought it to the White House," Springer is quoted as saying, while his show's executive producer takes credit for "creating reality TV, which ruined television, and then the country."

This topic simultaneously demonstrates some of the limitations of Benes' central thesis, which ironically is weakest when he tries to fit his given examples into his target year. Most broadly, he writes that 1999 was when Springer truly became a pop cultural force, referenced (or appearing in) multiple Hollywood films and hosting an MTV Spring Break version of his show called Springer Break. But Springer Break actually premiered in 1998, with a second airing the following year.

Regarding reality TV, Benes says the 1999 premieres of films like The Truman Show and EDtv and shows like Big Brother "toyed with the concept that watching people do ordinary everyday tasks in artificial environments was exciting." But The Truman Show premiered in 1998 (Benes notes that it "came out on home video" in 1999). Big Brother, meanwhile, premiered in the U.S. in July 2000—and was preceded by nearly a decade by The Real World, which was itself inspired by An American Family, the 1972 PBS documentary miniseries that depicted a middle-class family in Santa Barbara.

In her 2022 book True Story: What Reality TV Says About Us, the sociologist Danielle Lindemann argued that while reality TV "as we know it today" largely springs from The Real World, its origins go back decades—perhaps as far as the first televised iteration of Candid Camera in 1948. "While it's fruitless to try to establish a singular starting point for the genre," Lindemann wrote, "reality TV was not a flash storm that arose suddenly on a sunny day. It had been brewing for quite some time."

Benes also notes the rise of video games not only as a popular pastime but also as a target of elite censorship—most prominently, when blamed for the April 1999 shooting at Columbine High School. Benes singles out Grand Theft Auto 2, released in October 1999, as an example of the popular backlash against violent video games. But for anyone familiar with the history of video game moral panics, that game's release is overshadowed by its sequel, Grand Theft Auto III, two years later. The latter title's violent 3D graphics and profane voice acting, each a first for the series, launched the previously modest-selling franchise onto both the bestseller charts and the nightly news, and made its subsequent titles the subject of congressional inquiry. Grand Theft Auto 2, by contrast, was largely considered a retread of its predecessor and has sold fewer copies than any other main title in the series.

Benes is strongest when he eschews the premise of fitting his examples into a single year and merely presents low culture as the product of democratization, removing barriers to participation between social strata. "Since the invention of the written word, there have always been crusaders blaming social ills on new entertainment forms," he writes. "Today, politicians ban TikTok. Technologists warn that AI will cause human extinction. Social media receives blame for violent crimes that used to be aimed at video games. As soon as one panic folds, new ones begin."

Benes notes that studies consistently fail to show a causal link between video games and real-world violence, yet censorial scolds never let that stand in their way. Before video games, they blamed TV—and rock music, comic books, radio, movies, all the way back to the printed word itself. In each case, the masses outlasted the alarmists.

"Over the past several hundred years, new entertainment, usually targeted at young people, has become despised, blamed for societal problems, and threatened with legal sanctions," Benes adds. "After the entertainment has been around a few decades and its audience has aged, pressure reduces, old fears become laughable, legal protections arise, and free-speech rights expand." Low culture is a story of technological advances that enabled broadcast to a mass audience.

This had positive spillover effects. In a chapter on internet pornography, Benes notes that "porn's biggest online impact really came from how it shaped technologies that became common in people's everyday lives. Pornographers didn't invent the internet, but they commercialized it." Indeed, many innovations underpinning the modern internet—like high-capacity bandwidth, streaming video, and secure payment processors—were originally developed for distributing smut over the web. (Titillating but nonpornographic content played a similar role. Google Image Search was created as a way to find pictures of Jennifer Lopez in the plunging-neckline Versace dress she wore to the 2000 Grammy Awards, and three engineers created YouTube partially as a space to host a clip of Justin Timberlake accidentally revealing Janet Jackson's bare breast at the 2004 Super Bowl Halftime Show.)

Even legislation against low culture had catalyzing effects, albeit accidentally. Congress drafted the Communications Decency Act of 1996 specifically to restrict access to internet pornography. The bulk of the law would be struck down for unconstitutional infringements on speech, but one provision that survived was Section 230, which conferred legal protections on platforms that host others' content and enabled the rise of social media, and the web more broadly, over the next three decades. "The speech protections in Section 230 will likely come under duress as lawmakers consider regulating tech companies to curb the social ills they foster," Benes warns.

The expansion of lowbrow culture also opened the U.S. to the rest of the world. "By the late 1990s, pop culture had become America's biggest export," Benes writes. "This happened after the fall of the Soviet Union opened markets for Western entertainment. Because deregulation allowed US media companies to become much larger than foreign competitors, American entertainment held advantages breaking through international markets. What did America create that the rest of the world wanted? Trash." Talk shows, pro wrestling, porn, and all manner of lowbrow content numbered among America's cultural output.

For all the harm trashy entertainment is accused of doing, Benes notes, the democratizing aspects that enabled its rise in the first place also signal a positive path forward: "If we truly want our civics to improve, consider the programming changes that shook up the entertainment industry, which went on to shake up politics. Across elections and talk shows, the audience members who make their presence most known have something in common—they actively participate."

Editor's Note: As of February 29, 2024, commenting privileges on reason.com posts are limited to Reason Plus subscribers. Past commenters are grandfathered in for a temporary period. Subscribe here to preserve your ability to comment. Your Reason Plus subscription also gives you an ad-free version of reason.com, along with full access to the digital edition and archives of Reason magazine. We request that comments be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment and ban commenters for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

Hey, we can't all listen to NPR on the way to the opera.

And good thing we don't.

The fun of 90s media has mostly been replaced due to the efforts of political correctness and wokeness. They took their new sacred cows too seriously to be entertaining. At the same time, sex and all manner of deviant and socially degenerate behavior was praised as highlighted by the rise of reality tv. As we progressed into the social media age we got a consumer with a short attention span. Our current social media is interwoven with traditional media and is basically just expression without message. Those tiktoks with the template "______ got me feeling like *does dumb dance*" highlights the lack of any thought or message. When we do see a message it is the new trendy leftist cause that is hammered to death in lieu of progressing a solid coherent story.

I think his examples of "high brow" media actually show cultural degradation as well under a thin veneer of elitist aesthetics. I'd rather have more Adam Sandler movies full of fart jokes or Austin Powers innuendo-fests than much of what is fed to us now. There's a reason movies like Top Gun Maverick do so well. They harken back to a simple coherent story with good characters doing great things. Most movies and shows I watch now have no sympathetic characters and a sloppy story.

"no sympathetic characters"

I immediately think of Yellowstone. Every main character is an utterly selfish, depraved killer. Who do you cheer for?

I find myself cheering for everyone's death. At best I'll find a secondary character I like who quickly disappears. I'm not sure if they expect me to cheer for their awful characters or if they are feeding a diet of nihilism and apathy. I had no problem with complex antiheroes or mixed morality, but all too often the main characters are evil and stupid. New media in general comes across like content without message or meaning.

nihlism and apathy.

Yeah, modern culture is capable of writing crude stereotypes but is utterly incapable of writing actual characters.

Every gay person is not a hero. Every white man is not just waiting to oppress people.

Media is HEMHORRAGING money because they make fucking awful content. Ignoring the obnoxiousness of its star, Snow White was just a damned terrible movie with abysmal CGI and nothing remotely special to overcome its shortcomings. Marvel films were first unique (superhero-based movies were not frequent for a long while) then well-written...then they let modern writers take a crack and Marvel is now a money pit. Star Wars is a money pit (they made the fucking prequels look like good movies now in comparison). There is nothing on TV I find terribly entertaining.

What is called low brow here is ACTUAL content. What we have now is mind-numbing dreck that a few morons want to shout from the rafters is REALLY top of the line and amazing.

I don’t want to go through the Y2K madness again.

"Low culture" is defined as popular culture that is less sophisticated and more mainstream

"Those dern kids! Why don't they just sit down and play tiddlywinks and watch the Howdy Doody Show like I did! Maybe go out and play stickball and chew some bubble gum!"

OK boomer.

You mean the culture of 20-30 years ago created the culture of today?

You mean the culture of the 1920s created the war years of the 1940s?

You mean the children of the greatest generation of the 1940s created the counterculture of the 1960s?

You mean backlash to the 1960s led directly to the Reagan years of the 1980s and Alex P. Keaton?

You mean the 1980s-90s led to the Hope and Change election of Obama in 2008?

From his picture on Mises Ross Benes looks to be about 30. No one over 50 would have thought about writing a "water is wet" book.

This is a hilariously bad take from the author. I know Lancaster probably wasn't born when the century rolled over, but the "evidence" proffered by the book he is reviewing is heavily interpreted and overly tortured to meet the author's hypothesis.

Look, Pop Culture is wiiiiide open to interpretation. It is basically a Rorschach test- you can look at it and find whatever you want. Case in point:

The author tells us American Beauty- an independent film full of bold cinematography, complex characters, "Tale of a Death Foretold" storytelling, and filled with accomplished actors- is an example of "Low Brow Culture" merely because it was so loosely based on a tabloid story that you'd have to squint while drunk and sniffing glue to see the resemblance. Meanwhile, Sopranos is held up as high culture because...uh...reasons? For the record, Sopranos owes much of its early success to being one of the first TV Series to regularly feature sex, nudity and bloody violence.

My point isn't to say American Beauty is higher culture than Sopranos. There are points to be made on either side. THAT is the point: Each can be an example of cultural touchstones that prove we are producing high-brow culture, or that we are succumbing to low-brow impulses. It is all one big exercise in navel gazing.

Indeed the entire thesis is silly. If Low-Brow Culture reached it's "zenith" in 1999, then...uh...by definition that means it is on the wane. What is replacing it, if not higher culture? Less-Low Brow Culture?

Look this is all silly. Every time we get new forms of communication, this cycle occurs. Whether it was the printing press, or telephones, Radio or TV- as soon as they reached mass audiences, a different flavor builds up. The elites who have established themselves as gatekeepers for the media of the time always wail and wring their hands about the dumbing down of society, when in fact, despite the growth of mass media, these earlier forms of media still exist.

What these people can't handle is folks having fun. Opera and classical music still exist, and I guarantee you millions upon millions more people listen to opera today than did in the 1500s. And the people who DIDN'T listen to Opera were listening to baudy tavern music, minstrals in the town square or no music at all. Likewise, when the printing press gave literature to the masses, it was filled with polemics and romance novels. So what? The people consuming these things weren't subsisting on illuminated manuscripts before. They had nothing.

"The author tells us American Beauty- an independent film full of bold cinematography, complex characters, "Tale of a Death Foretold" storytelling, and filled with accomplished actors- is an example of "Low Brow Culture" merely because it was so loosely based on a tabloid story that you'd have to squint while drunk and sniffing glue to see the resemblance. Meanwhile, Sopranos is held up as high culture because...uh...reasons? For the record, Sopranos owes much of its early success to being one of the first TV Series to regularly feature sex, nudity and bloody violence."

I liked American Beauty and did not get anything resembling an Amy Fisher story in it. And Sopranos was wildly overrated. The sex and violence is why HBO shows were overrated for as long as they were.

This was the first time I'd heard that American Beauty was in any way related to the Amy Fisher saga. But who knows... for instance I learned that Prince's 1999 was about the rollover from 1998 to 1999, when lo these many years I thought it was rolling into the 2000s.

The lyrics say it was the 1999-2000 New Year's Eve to New Years.

They say, 2000 Zero Zero, party over

Oops, out of time

So tonight I'm gonna party like it's 1999

Thank you for your research. I recommend you pass that on to the vertical-id-having Joe Lancaster.

Why pick on 1999? Any year is dominated by pop culture because that's where the people are. And TV especially is 99.94% trash.

WHOA! What .06% is NOT trash?

Accused: Guilty or Innocent on A&E

idk I kinda miss mme. dillinger sporting babydoll tees everywhere we went ... and the X was laced with heroin sometimes not fentanyl all the times ... phish is better now as a band but I suppose that comes with practice

If 90s pop culture was trash (which it largely was), today's is a flaming tornado of shit (with better video quality).

seriously. is today's pop culture even popular?

At least in the 90s we could come together around watching all the crappy pop (which, looking back, included a lot of great stuff, especially in rock and rap music) on MTV.

90s music was awesome. Alice in Chains is untouchable.

Yeah, original AIC is the shit. Haven't listened to much of the post Layne version.

there's a post-Layne version?

It's ok. Cantrell is the more talented musician anyway. Without Layne it does lose its grit and heart.

You poor tin eared bastards……

If Hammer Pants are wrong, I don't want to be right.

please Hammer don't hurt 'em

I was trying to spin a comment in under 300 words about low-brow culture is literally the democratization of media, but then I my gen-x brain said, "Fuck it, too far".

^^ genX is always erasing half their texts to you and your phone shows it now

Can anyone really be this stupid? --

In 1982, Prince first sang that he planned to party "like it's 1999." But on New Year's Eve of 1998, as MTV counted down to the actual year 1999, it wasn't the Purple One who performed that song in Times Square. As Ross Benes notes in his new book 1999: The Year Low Culture Conquered America and Kickstarted Our Bizarre Times, it was the nu metal band Limp Bizkit that performed one of the 20th century's most recognizable dance hits, swapping the original's synths and funky basslines for chugging guitars and hip-hop breakbeats.

"Party like it's 1999' doesn't refer to the change from '98 to '99.

It refers to the turn of the millennium, from '99 to '00.

How did we get to the point where intensely filmed, written about, and recent history is treated like undecipherable pictoglyphs from out of the mists of antiquity?

Because most younger writers are myopic hipsters.

And he's a cited pop culture expert by NPR.

The event was BT (Before Twitter).

I noticed that too. I was too lazy to do a paragraph-length riff on it, so instead I did one on The American Family.

By the way, thank you for this, well done:

How did we get to the point where intensely filmed, written about, and recent history is treated like undecipherable pictoglyphs from out of the mists of antiquity?

I would trade today for the late 90's in a heartbeat.

I remember when racial tensions were not too bad --- well, until Obama decided he needed to bring them back in full to protect his Presidency and shut down criticism of him.

He was such a shit President.

the 1972 PBS documentary miniseries that depicted a middle-class family in Santa Barbara.

ehh... "middle class" is a bit of a stretch... perhaps upper middle class?

For your information, I actually... *clears throat* remember this show. And I would consider my upbringing to be somewhat middle class by (1970s standards) and to me, they felt fairly wealthy.

This whole family-- even then felt like they were picked because they knew a PBS producer and ran in those circles. I mean, when looking back on it, the show feels almost scripted...

I remember being slightly suspicious because everyone felt a little too hip, a little too good looking... just a little too everything. In other words, they weren't typical, they were quite a-typical. Like the type of family Andrew Sorkin would make up in his head:

Far out, middle class family!

Random Host: "You are not the father!"

Guest- Random Male: "Yaaaayaaahhhhh!"

Guest- Baby Momma 3574: "He is, he is. I know he's the father of baby #6, I just know it."

I liked how nobody ever seemed to want to say "You know, if you are not SURE who the father is, maybe you need to be a wee bit less of a gutter slut?"

...

Why do they call those "reality shows" instead of "game shows'?