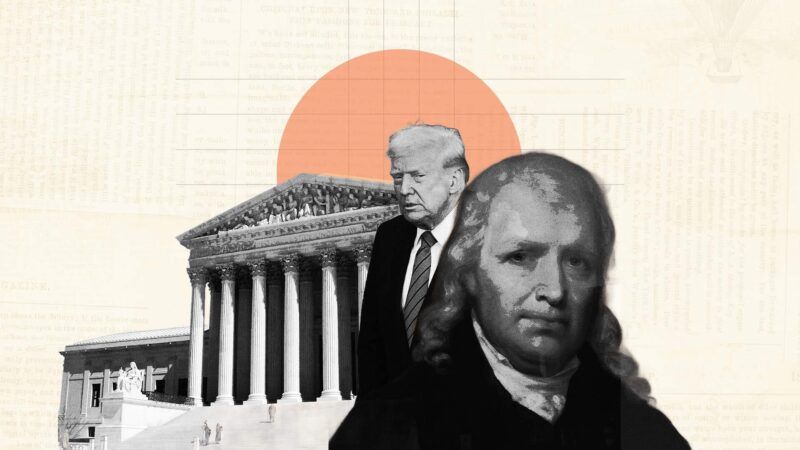

What Trump Should Learn From the Impeachment of Justice Samuel Chase

Trump wants to purge the federal bench of judges who disagree with him. Thomas Jefferson did too, and it didn't work out.

The first federal official of any kind to be impeached and removed from office was a federal judge from New Hampshire named John Pickering. He was an appointee of President George Washington and was generally aligned politically with the Federalists. After Thomas Jefferson was elected president in 1800, the Jeffersonians went on the attack against what they saw as untoward Federalist influence over the federal courts.

Pickering was vulnerable. He had faced credible past accusations of both mental instability and drunkenness. Did they count as "Treason, Bribery, or other high Crimes and Misdemeanors," which is what Article II, Section 4 of the Constitution requires for a judge to be "removed from Office"? Or perhaps he had run afoul of Article III, Section 1, which states that "the Judges, both of the supreme and inferior Courts, shall hold their Offices during good Behavior." Either way, a majority of Congress wanted him out and the requisite two-thirds majority was present in the Senate to do it. Pickering got the boot in 1803.

That set the stage for the real showdown over the power to impeach judges. Emboldened by the successful removal of Pickering, the Jeffersonians turned their glare on Supreme Court Justice Samuel Chase. An outspoken Federalist, Chase especially drew the ire of the Jeffersonians because of his role as the presiding trial judge in several Sedition Act prosecutions carried out by the Federalist administration of President John Adams.

Among those prosecutions was the 1800 trial of a bombastic political writer named James Callender. An ally of the Jeffersonians (in fact, Callender was partially bankrolled by Jefferson himself), Callender had published a scathing attack on both the Federalists in general and Adams in particular, describing Adams as "mentally deranged" and a "hideous hermaphroditical character, which has neither the force of a man, nor the gentleness and sensibility of a woman." That bit of election-year mudslinging landed Callender behind bars under the censorial terms of the Sedition Act, which the Adams administration happily enforced against him. Later, after Jefferson had defeated Adams to become president, Callender was pardoned by Jefferson.

The articles of impeachment filed against Chase in 1804 mixed legal complaints with political ones. One of them described Chase's conduct as the presiding judge in Callender's trial as being motivated by a "spirit of persecution and injustice," as well as an "intent to oppress, and procure the conviction of, the said Callender." Another article of impeachment charged Chase with conduct "highly indecent, extra-judicial, and tending to prostitute the high judicial character with which he was invested, to the low purpose of an electioneering partizan."

But two-thirds of the Senate did not buy it. Or perhaps it would be more accurate to say that enough senators, including a sufficient number of Jeffersonians, recognized the dangerous precedent that they would be setting if they removed a sitting member of the Supreme Court over what appeared to be mostly political disagreements. So Chase kept his job. He has remained the only Supreme Court justice ever to be impeached.

The Chase affair offers certain lessons for our own politically fraught times. Much like Jefferson, for example, President Donald Trump clearly likes the idea of purging the federal bench of judges who disagree with him. But Trump may find out, just as Jefferson did, that even some of his own allies lack the stomach for waging such an unsavory attack on the independence of the judiciary. After all, if the Republicans under Trump actually succeeded in impeaching and removing a federal judge for political reasons, the Democrats will undoubtedly repay them in kind at the first opportunity. It will be a race to the bottom that does lasting—and perhaps even irreparable—damage to the judicial branch.

In a way, this is all quite similar to the fate of Franklin Roosevelt's notorious court-packing plan of 1937. Roosevelt's scheme for undermining the independence of the judiciary failed in large part because members of Roosevelt's own party worked against it. Will any members of Trump's party do the same if the impeachment threats ever go beyond the talking point stage?

Currently, that question is moot because the Republicans lack the requisite two-thirds majority of votes in the Senate needed to remove anybody via impeachment. Time will tell if that unforgiving math alone is enough to prevent Trump from following any further in Jefferson's missteps.

Show Comments (47)