A State Cop Lionized for Nabbing Drunk Drivers Is Suspected of Taking Bribes To Let Them Off the Hook

New Mexico State Police Sgt. Toby LaFave, "the face of DWI enforcement," has been implicated in a corruption scandal that goes back decades and involves "many officers."

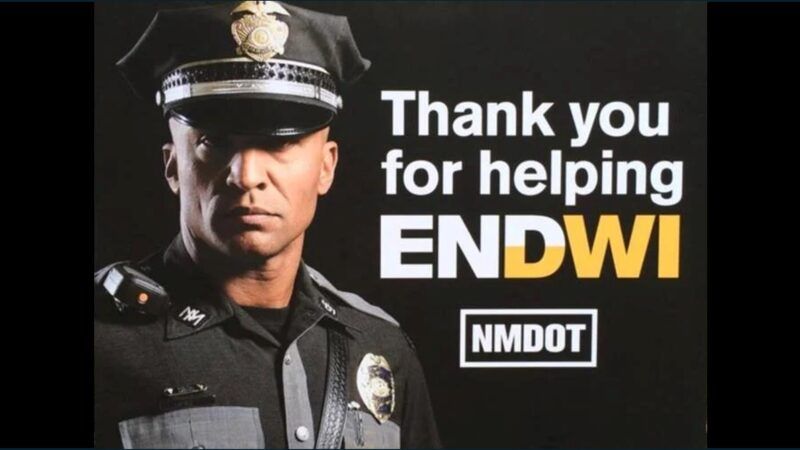

"Thank you for helping ENDWI," says a poster that the New Mexico Department of Transportation produced as part of its long-running campaign against drunk driving. The poster features a photograph of New Mexico State Police (NMSP) Sgt. Toby LaFave, an award-winning, record-setting officer who was "the face of DWI enforcement" for the NMSP, appearing in anti-DWI billboards and videos because he was celebrated for his dogged efforts to protect public safety by nabbing intoxicated drivers.

Last Friday, NMSP Chief Troy Weisler revealed that LaFave had been placed on paid leave pending the outcome of an internal investigation triggered by a huge corruption scandal involving cops who took bribes in exchange for making DWI cases disappear. According to federal prosecutors and Thomas Clear, the Albuquerque defense attorney at the center of the scandal, the corruption goes back decades and involved "many officers." While most of the crooked cops served in the Albuquerque Police Department (APD) unit charged with apprehending drunk drivers, where corruption was pervasive, Clear says he also bribed employees of the NMSP and the Bernalillo County Sheriff's Office.

LaFave's alleged participation in what prosecutors call the "DWI Enterprise" underlines the question of how the conspiracy, which was uncovered by an FBI investigation that became public in January 2024, went undetected for so long. For at least two dozen years, Clear says, he routinely paid cops to help his clients avoid prosecution and keep their driver's licenses. His collaborators did that either by refraining from filing DWI charges or by deliberately missing pretrial interviews, hearings, or trials, allowing Clear to move for dismissal.

That arrangement endangered public safety by letting drunk drivers off the hook. It also gave cops a financial incentive to arrest innocent drivers on bogus DWI charges and refer them to Clear, who typically collected cash fees ranging from $6,000 to $10,000 and gave the arresting officer a cut. Meanwhile, those cops not only avoided exposure as criminals; they were lionized as dedicated public servants who were making the roads safer.

When he pleaded guilty to federal bribery, extortion, and racketeering charges last week, Clear said he had been bribing cops, including "almost the entire APD DWI unit," since "at least the late 1990s." The APD officers who took payoffs included Honorio Alba Jr., who pleaded guilty to similar charges on February 7. As late as last December, the APD was still bragging that Alba had been selected as "Officer of the Year" by the New Mexico chapter of Mothers Against Drunk Driving (MADD). But Alba's celebrity paled beside LaFave's.

LaFave, who joined the state police in 2012, received that MADD honor twice and was named "State Police Officer of the Year" in 2012. The "DWI King" bragged that he had arrested more drunk drivers than any other officer in the NMSP's history, and his work repeatedly attracted laudatory news coverage.

In September 2017, KRQE, the CBS affiliate in Albuquerque, reported that LaFave had "reached a milestone when it comes to putting drunk drivers behind bars" by making "his 100th DWI arrest." The station noted that "you might recognize him from the ENDWI billboards" that presented him as the epitome of the state's anti-DWI efforts. Pete Kassetas, then the NMSP chief, said "LaFave should be applauded for his commitment to keeping the roads safe from drunk drivers."

LaFave was back in the news the following month, when KRQE reported, under the headline "State Police Officer Moved to Tears After DWI Stop," that he had "spotted a driver in a gold Cadilac going 96 mph down Interstate 40, weaving through traffic." When LaFave pulled the car over, "he immediately noticed a little girl unbuckled in the front seat and asked the driver what she was thinking driving like that." After the driver failed "multiple" roadside sobriety tests, LaFave arrested her for DWI, but he could not get over the endangered child. He "got choked up" while "speaking with someone on the phone about picking up the little girl." Walking back to his patrol car, he told a fellow officer, "That makes my heart hurt." It was "a normal night for State Police Officer Toby Lafave," KRQE said.

The station's praise continued. "You've seen him in the DWI ads and you've seen him out on the streets," a November 2018 story began. "But in person, State Police Officer Toby Lafave will tell you, he does this job for people like you and me." The station noted that LaFave had already made 130 DWI arrests that year, nabbing "more drunk drivers than any other cop." Here is how he described his motivation: "It's very disheartening knowing that people continue to drink and drive, seeing all the commercials, seeing all the ads, seeing all the fatals, children in vehicles, and they still continue to do it….I believe that DWI is a very serious thing." For LaFave, KRQE said, "it's a never-ending job—one that drives him to save lives."

Last June, six months after news of the FBI corruption investigation broke, KRQE highlighted LaFave's arrest of an intoxicated APD officer who was speeding to work in his SUV when LaFave pulled him over. The station noted that LaFave "is well known in the state for his career putting drunk drivers behind bars."

KRQE is not celebrating LaFave anymore. "Since Lafave was put on leave," it reported last Friday, "the Bernalillo County District Attorney has added him to the Giglio List, meaning he is not considered a credible witness in court. To date, the DA has dropped 230 cases involving officers implicated in the DWI enterprise. A spokesperson for the DA said they are currently reviewing Lafave's cases to see what may need to be dropped."

LaFave "filed at least 1,300 felony and misdemeanor DWI cases from 2009 to this month," the Albuquerque Journal reports. "Of the 31 DWI cases where LaFave was the arresting officer and Clear was the defense attorney, 17, or 57%, were dismissed."

Like KRQE, Chief Weisler seems to be having second thoughts about LaFave's performance. "Any misconduct or criminal behavior within our ranks will not be tolerated," he said in a press release. "The New Mexico State Police holds its officers to the highest ethical and professional standards. If it is found Sergeant Lafave's actions have violated the law or our policies, he will be dealt with swiftly and decisively. I also want to assure the public that our internal investigation is a top priority. I will do everything in my power to ensure any State Police officer who engaged in corrupt behavior is prosecuted to the full extent of the law. We will not allow the actions of any individual to tarnish the reputation and sacrifice of the men and women in this department who uphold their oath with pride and honor every day."

Weisler's stance is refreshing compared to Bernalillo County Sheriff John Allen's attitude. In a recent interview with KRQE, Allen sounded more upset about the FBI's investigation than he was about the corruption it uncovered. Although he placed Deputy Jeff Hammerel on administrative leave after learning that he was a target of that probe, Allen said he was not conducting an internal investigation and did not plan to do so.

"I know that there's nothing to worry about right now," Allen said. "It's an investigation. I was not naive to the fact that this could possibly pop up. If it's happening at Albuquerque Police Department, and we all work so closely together, this could affect my agency." When KRQE asked "if he believed that Hammerel was the only [deputy] who was involved in the DWI scheme," Allen replied, "I don't believe anything at this point."

Albuquerque Police Chief Harold Medina, for his part, has repeatedly promised to "make sure that we get to the bottom of this." But by his account, Medina, who joined the APD in 1995 and has run or helped run the department since 2017, had no idea what was going on in the DWI unit until he was briefed on the FBI investigation in October 2023. He was so oblivious, in fact, that he put former DWI officers in charge of the APD's internal affairs division, where they were well-positioned to protect Clear's racket.

Given the pervasiveness of corruption in the APD's DWI unit, the turnover of cops assigned to it, and the length of time that the "DWI Enterprise" operated, it probably involved dozens of officers. According to a lawsuit by drivers arrested for DWI, Medina "ratified the conduct" of those corrupt officers by "failing to intervene after receiving multiple notices" that they were "violating the law." In December 2022, for example, the APD got a tip that DWI officers, including Alba, were getting paid to make sure that cases were dismissed. The investigation of that tip went nowhere.

That was not Medina's only chance to clean his own house instead of waiting for the FBI to discover the mess. "Systems that struggle, systems that have loopholes, are really open to corruption," he said a year ago, alluding to DWI dismissals prompted by officers' failure to show up at crucial proceedings. He made it sound as if he had nothing to do with the "systems" that are "really open to corruption." But the lawsuit notes that the APD failed to keep track of DWI officers' appearances, let alone ask why they were conveniently absent so often in cases involving Clear's clients.

The connivance of senior APD officers who had participated in the "DWI Enterprise" and did their best to protect it helps explain why it lasted so long. But that explanation goes only so far.

The FBI received multiple reports from people who said APD officers had referred them to Clear after arresting them, recommending him as a lawyer who could get their charges dismissed. As an added incentive to hire Clear, the cops often retained the arrestees' licenses or other personal effects and handed them over to Clear's investigator, Ricardo Mendez, who admitted his role in the scheme when he pleaded guilty last month.

This thinly veiled extortion affected many people, and it persisted for more than two decades. It is hard to believe such manifestly suspicious conduct never came to the attention of local authorities with the power to do something about it. Such systematic corruption would have been possible only if local officials who were not directly involved in it looked the other way.

Show Comments (12)