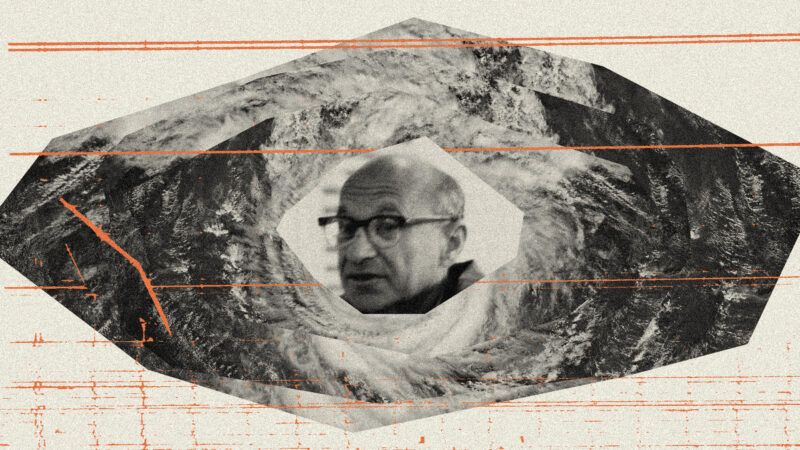

How Milton Friedman Can Help Us Get Through Hurricane Milton

To give storm victims the best chance at recovery, let local knowledge and markets guide decisions.

Hurricane Milton is set to make landfall on Wednesday between Cedar Key and Naples, Florida, threatening significant damage along the Gulf Coast. The region is still reeling from Hurricane Helene, which claimed at least 234 lives and caused over $30 billion in property damage, according to CoreLogic, a real estate information services provider. Despite expensive emergency aid programs, too many Americans remain in dire straits. Instead, policymakers would be wise to consult the teachings of Nobel laureate economist Milton Friedman: "you don't let prices rise, you destroy the system…which coordinates the activities of different people."

It's understandable to call for government assistance when faced with the havoc wreaked by natural disasters. But the government is just one kind of human institution—one that often lacks sufficient information to help people. To deliver disaster victims the goods and services they desperately need, it's better to rely on market mechanisms.

In the early and mid-20th century, so-called market socialists Oskar Lange and Abba Lerner argued that centrally planned economies are theoretically more efficient than capitalism. But Ludwig von Mises and Friedrich Hayek disabused technocrats of such fatal conceits, winning the calculation debate and elucidating the knowledge problem. The historical record has empirically substantiated the superiority of markets to create, allocate, and innovate.

"But," the stubborn statist objects, "markets only work under normal conditions; in emergency situations we need the government to resolve the crisis." While such arguments are politically popular, they are economically vacuous.

The state does not become omniscient during times of crisis and the price system that conveys information about local circumstances is especially useful during such times. Recognizing their lack of knowledge, governments should adopt the following laissez faire policies to allow those with the know-how to recover from disaster.

Before: Don't create moral hazard

The federal government should not distort the single most reliable signal of risk: homeowners insurance. By subsidizing the premiums of insurance in Special Flood Hazard Areas (SFHA) through the National Flood Insurance Program, the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) has shielded residents from the expected consequences of living in disaster-prone areas.

During: Don't impose price ceilings

Economist George Horwich argues that post-World War II West Germany and Japan show the salutary effects of markets in the aftermath of disasters because the economic and human devastation suffered during wartime is analogous to that imposed by natural disasters. Notably, recovery in West Germany and Japan "began only with the removal of price ceilings imposed during the wartime inflations," says Horwich.

Increased prices for gas throughout the Gulf Coast during Hurricane Katrina "attracted imports of gasoline from overseas," increasing supply and lowering prices, explains the Foundation for Teaching Economics. Imposing price controls denies consumers the ability to express "their preferences and denies producers the information" they need to allocate their goods to their highest-valued use, Horwich concludes.

After: Suspend rent controls

In the aftermath of a domicile-destroying disaster, one of the most important things to do is house the homeless. To incentivize the construction of new apartments, condos, and single-family houses, policies should be adopted that increase expected returns. The simplest way to do this is eliminating rent controls that "inhib[it] the rapid market-wide expansion and sorting out of the remaining housing stock," Horwich explains.

The absence of rent controls alone enabled the rapid rebuilding of San Francisco following the earthquake of 1906 that killed 3,000 residents and destroyed 80 percent of the city's buildings. Following a 1985 earthquake, Mexico City did not witness the same recovery thanks to a 1947 rent control law that "left owners of nearly a square mile of real estate [with] no incentive for repairing it," per Horwich.

The laws of supply and demand do not disappear in the event of a disaster: Markets still direct resources to their highest-valued use while encouraging their conservation—exactly what needs to be done in response to supply shocks.

While high prices do prevent some from buying what they need, scarcity, though tragic, is inevitable in the immediate aftermath of a disaster. Government-imposed price controls perpetuate the shortage while market prices incentivize entry and expand supply. The government should avoid scrambling the very signals that allow consumers and producers to recover from devastation.

Editor's Note: As of February 29, 2024, commenting privileges on reason.com posts are limited to Reason Plus subscribers. Past commenters are grandfathered in for a temporary period. Subscribe here to preserve your ability to comment. Your Reason Plus subscription also gives you an ad-free version of reason.com, along with full access to the digital edition and archives of Reason magazine. We request that comments be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment and ban commenters for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

Read an interesting comparison of the British and German economies following WW II. Obviously Britain's infrastructure had suffered far less damage than Germany, and fewer people died. But Britain kept some price controls and rationing books into (IIRC) the late 1950s, while West Germany dropped them around 10 years sooner. The difference in Germany no longer having much of a military made a difference too, and I don't think Britain got any Marshal Plan aid, but the key difference was the central planning, which destroyed the UK economy.

What about Michael Bolton?

JD Vance is wrong about Michael Bolton.

Thankfully, the Governor of Florida is NOT a socialist Big Brother Democrat, whose first responses (after hurricanes) have been to ban all retailers from increasing prices (as supply is very limited while consumer demand skyrockets).

It's hard to tell through this medium whether you're being sarcastic or whether you actually believe that.

While all of this is true, relying on the truth underestimates the true hidden motive of the socialists: that they are not even remotely interested in efficiency or making society more fair; and that those of us who see through their pretenses can only rely on the actual track record of actual socialist governments throughout history.

Quit Stalin and provide some examples.

I will. After I finish folding my Lenins.

Needs MAO testing!

I’m too busy studying the pols on pot.

""But," the stubborn statist objects, "markets only work under normal conditions; in emergency situations we need the government to resolve the crisis."

How did that work out during Hurricane Katrina?

By subsidizing the premiums of insurance in Special Flood Hazard Areas (SFHA) through the National Flood Insurance Program, the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) has shielded residents from the expected consequences of living in disaster-prone areas.

This was not done under FEMA’s own initiative but at a higher level of government.

There should be no such Federal subsidies. If a state wants to subsidise, fine. Let the states’ own inhabitants bear the cost.

"you don't let prices rise, you destroy the system…which coordinates the activities of different people."

While he was FL governor and after a h'caine, Jeb Bush outlawed 'price gouging' for generators, which then stayed in warehouses all over the country instead of going to FL where they were needed.

Radio talker Neil Boortz always used to use emergencies to explain how "price gouging" is not price gouging at all but a signal to producers and consumers.

He would say something like "Imagine a family of 4 fleeing Florida inland to avoid a hurricane. Once they clear the danger zone, they start looking for a hotel with vacancies, and when they find one they decide to stop and check in. It's not a nice hotel, it's a highway-side motel with (normally) cheap rooms, let's say $100/night normally. Mom & Dad are happy find that there are still two rooms available.

Now here's two situations.

In the first case, 'price gouging' laws prevented the management from increasing their prices. Mom & Dad decide to splurge and take both rooms, one for the kids, and one for themselves. They take their keys and head off to their rooms. Moments later, another family shows up and has to be told: "Sorry, just rented the last rooms and hadn't had a chance to turn of the Vacancies sign".

In the second case, without such laws, the management realizes that rooms will be in high demand and short supply. The clerk tells Mom & Dad that rooms are $250 each. Not willing to pay an extra $250 to give the kids their own room, they grudgingly (knowing it's normally $100) take the one room, their key and head off. Moments later, another family show up and is told "Yes, there's one room left."

A similar story about gas at $10/gallon vs 'price controlled' making people chose "How much gas do I *really* need to get through the next few days?" vs "Might as well top off the tank, just in case!"

Ack, Neal not Neil

Ah. Need another law for room rationing.

Yes, because despite having no communications, no transport, no money, no houses, no food, no water, and bodies to bury, hurricane victims will have perfect information about the market.