How Inflation Breaks Our Brains

From salt riots to toilet paper runs, history shows that rising prices make consumers—and voters—grumpy and irrational.

When Russian peasants set fire to hundreds of buildings in Moscow in 1648, the acute cause was a sharp rise in the price of salt. When they rioted again 12 years later, it was to protest a government policy that made copper money equal in value to coins made from silver—a policy that naturally caused widespread price inflation.

An increase in the price of bread, and an inept government response to it, helped set the French Revolution on its bloody course.

Periodic violence targeting Jews and other minority groups throughout European history has been linked to inflation and other sources of economic instability. The most infamous and horrific of those incidents, of course, began as an attempt to scapegoat Jews for the spike in inflation that plagued Germany in the wake of World War I. American history, too, is littered with panics, riots, and upheaval caused by sudden rises in prices and the public's perception that they are being ripped off. In the early days of the American experiment, indebted Massachusetts farmers took up arms against the new federal government's monetary policies. Two centuries later, dozens of farmers drove their tractors to the front door of the Federal Reserve in downtown D.C. to protest rising costs.

It may be tempting to dismiss the unsettling history that links high inflation with political unrest and aggressive xenophobia. Americans living today are the richest cohort of human beings ever to inhabit the planet. Surely we're not as susceptible to the psychological effects of inflation as our forebears, for whom a spike in the price of basic goods might be a matter of life and death?

And yet we may not be as far removed from Russian serfs or Weimar Germans as we'd like to think. Just look at the panicked runs on toilet paper in the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic, and the social media–fueled outrage over last year's sharp increase in the price of eggs. Or there's the bipartisan political impulse to reduce international trade and limit immigration—policies that will not reduce inflation but attempt to deflect blame for it onto foreigners.

Milton Friedman famously described inflation as being "always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon." That's still true when it comes to the causes of inflation—more money chasing the same number of goods is a surefire recipe for higher prices. But it does not fully capture the effects of inflation, which academics are still studying.

Inflation, it turns out, is also a psychological phenomenon. It makes us angry. It makes us irrational. In any democratic system, that anger and irrationality can be quickly translated into poor policies—unless elected and unelected officials are prepared to withstand it, and to recognize that combating inflation often requires unpopular actions. Now is not the time to indulge the wisdom of the mob.

In short, inflation breaks our brains. It makes us poorer, and poorer citizens too.

'Paying Them Without Mercy'

Inflation has been a trigger for political and social unrest for as long as America has had its own paper money.

The country's first inflation incident occurred while the Revolutionary War was ongoing, according to Carola Binder, the chair of the Haverford College department of economics and the author of a new book, Shock Values: Prices and Inflation in American Democracy,which examines the interplay between rising prices and politics. The fledgling American government issued paper money, known as "continentals," to fund the war effort, but the bills were seen as being mostly worthless. As a result, inflation occurred.

"Inflation meant that debtors could pay off their debts in depreciated currency, which of course infuriated their creditors," says Binder. "The big problem was that creditors were forced to accept the Continentals in repayment for debts, even though the value of the Continentals had fallen."

John Witherspoon, one of the signers of the Declaration of Independence, dryly noted the humorous results. Rather than lenders pursuing borrowers to seek repayment, he wrote, creditors were "running away from their debtors, and the debtors pursuing them in triumph, and paying them without mercy."

A postwar period of deflation—in which prices actually fell—left some farmers unable to sell food at high enough prices to make payments on their mortgages. That triggered Shays' Rebellion, a violent Massachusetts uprising in 1786 and 1787. "The army eventually quashed the rebellion, but it sure made an impact," says Binder. "It showed the framers of the Constitution that price fluctuations affected not only the economic but also the political and social well-being of the states and the union."

Much of the first 100-plus years of U.S. history is marked by that same pattern of inflation and deflation, along with the corresponding panics, bankruptcies, booms, and busts. Each shift in the value of money triggered calls for political action, often in the form of protectionist schemes like tariffs or direct political intervention in the economy to set prices.

When the Federal Reserve system was created in response to the Panic of 1907, the new central bank was given a mandate to keep prices stable. In theory, that would remove the levers of monetary policy from American politicians, who had for decades used those powers to influence elections, reward friends, and punish enemies.

The Federal Reserve's main tool for combating inflation is the ability to raise interest rates. Higher interest rates make it marginally more attractive to save money rather than spend it, so dialing up interest rates can reduce the amount of money circulating in the economy and thus ease inflation.

Of course, people don't like higher interest rates either. When the Federal Reserve raised interest rates to combat inflation in 1980, homebuilders mailed lengths of lumber to Chairman Paul Volcker's office as a form of protest, since higher interest rates made it more difficult for Americans to afford homes (as is happening again today). Dozens of farmers staged a protest outside the Federal Reserve's headquarters in Washington. "They wanted a general lowering of interest rates. They also wanted the rates on loans to farmers lowered a little more than the rest," The Washington Post reported at the time.

That interplay between inflation and interest rates is essential to the Federal Reserve's mandate. It's also essential to understanding why so many Americans report being unhappy about the state of the economy today, even though inflation has fallen a long way from its mid-2022 peak and unemployment remains near historical lows.

Something Missing

The official story of inflation in the early 2020s is well known. There was a pandemic, and the government response at all levels was unprecedented. Businesses closed, unemployment briefly skyrocketed, and stimulus spending of borrowed dollars reached previously unimaginable heights. Supply chains were severely stressed. Consumer behavior shifted seemingly overnight. Trillions of dollars in monetary intervention spiked demand and, most importantly, meant that suddenly there was a lot more money sloshing around in the economy. Prices, naturally, rose quickly—and kept rising.

During the 12 months that ended in June 2022, consumer prices in the United States climbed by 9.1 percent, according to the Department of Labor. It was the highest inflation rate recorded in more than 40 years—and even that statistic fails to capture just how abnormal of an economic event this was.

Before 2021, the last full year in which America experienced an average inflation rate of more than 4 percent was 1991. There was only a single year (2008) from then through 2020 when the annual inflation rate exceeded 3 percent. During peak inflation in the first half of 2022, the price increases were two to three times worse than the worstbout of inflation that most Americans could easily recall.

It also means that even though inflation has fallen significantly since its mid-2022 peak, the current rate of 3 percent (in June 2024) is still high by recent historical norms. It's also well above the Federal Reserve's official target rate of 2 percent.

Consumers are still feeling the sting. An annual survey of Americans' economic opinions released in May found that inflation was the top worry for a third year in a row. Interestingly, the number of Americans who named inflation as their top concern has grown (from 35 percent in 2023 to 41 percent this year) even as the inflation rate has fallen. It dwarfs other issues: "The cost of owning or renting a home" ranked second at just 14 percent.

Inflation has fallen, but Americans are more worried about it than two years ago when it was running three times as high—and more likely to view the economy as a whole in a negative light. How can this be?

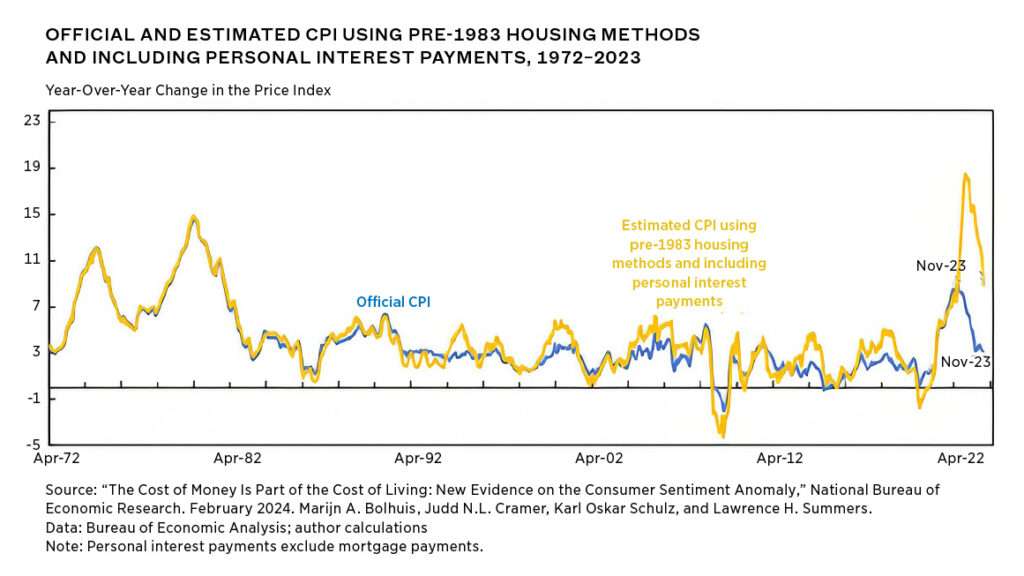

"We propose that borrowing costs, which have grown at rates they had not reached in decades, do much to explain this gap," argue economists from Harvard and the International Monetary Fund in a February 2024 working paper. The four authors, including Obama administration economic adviser Lawrence Summers, write that "concerns over borrowing costs…are at their highest levels" since the early 1980s.

To combat rising prices, the Federal Reserve raised its baseline interest rate 11 times from March 2022 to July 2023 in an attempt to curb rising prices. In total, the central bank has raised its baseline interest rate from near 0 to over 5 percent, and those changes have filtered into the economy in the form of higher borrowing costs for anyone who needs a car loan, a mortgage, a business loan, or some other form of debt.

But higher interest rates aren't taken into account in the government's official inflation calculation, known as the Consumer Price Index (CPI). To understand why that's significant, Summers and his three co-authors point to the process for buying a new car. The cost of new and used vehicles is weighted to account for roughly 7 percent of the monthly CPI, but the cost of financing a car is not included at all, even though more than 80 percent of all car purchases are made with a loan.

The same problem pops up when you look at housing. The monthly mortgage payment on the median-priced home in the United States has climbed from $1,621 in 2020 to $2,722 in July 2024. Yes, housing prices have increased during that time, but not enough to account for that 68 percent increase. The bigger factor—one that does not get included in the official CPI metrics, even though it makes a big difference to a potential homebuyer—is the increase in interest rates.

The paper's authors calculate that if the pre-1982 inflation metrics were being used today, the rate of price increases would have peaked at an astonishing 18 percent in June 2022 rather than 9.1 percent. In November 2023, the most recent month that the paper covers, inflation would have rung in at 9 percent instead of barely over 3 percent.

It's not just that the money in your wallet is worth less. The money you don't have—the amount you might need to borrow to make a big purchase like a home or car—is now further out of reach.

Being able to afford a mortgage or a car loan is "integral to American consumers' sense of their economic well-being but their price is not included in official inflation measures, it is no wonder that sentiment lags traditional measures of economic performance," the four economists write. "Consumers are including the cost of money in their perspective on their economic well-being, while economists are not."

And if inflation is worse than the official numbers would suggest, that's potentially a worrying sign for a variety of other social indicators too.

Facts and Feelings

If there's a silver lining to three-plus years of rising prices, it's that wages have been rising across the board too—and after the initial inflation surge in 2022, pay increases have actually outpaced the official inflation numbers. In fact, the Congressional Budget Office reported in May that average wages have grown faster than inflation at all income levels since 2019. President Joe Biden has touted rising wages as part of the White House's messaging strategy aimed at convincing Americans the economy is doing well.

Of course, the wages-are-growing-faster-than-prices argument doesn't include the toll that higher interest rates have taken.

Regardless, it seems like Americans' feelings don't care much about those facts.

New research from Harvard economist Stefanie Stantcheva shows that human beings are simply less likely to recognize the potential benefits of inflation—higher wages, chief among them—and will instead focus on the negatives. For her aptly titled paper "Why Do We Dislike Inflation?" Stantcheva interviewed more than 2,000 people. She concludes that most respondents believe wage increases are due to their on-the-job performance, while they view inflation as being to blame for their paychecks not stretching as far as before.

The bigger problem is that Americans don't see inflation as "a mere 'yardstick' or a unit of measure," Stantcheva writes. Instead, "individuals anticipate a variety of tangible adverse effects on both their personal financial situation and the economy at large."

That stress and uncertainty quickly turns into something else. In Stantcheva's survey, 48 percent of respondents were "angry" about inflation. This anger can be expressed in haphazard ways, though the most common responses are about what you'd expect if you've spent much time talking to people or scrolling through social media in recent years.

"The most common [target] is Biden and the administration ('I think it has to do with Joe Biden', 'Joe Biden's policies for this round of inflation') followed by Greed ('I believe the sole reason is greedy corporations who care more about their bottom line than actually helping people')," Stantcheva reports.

Meanwhile, just 13 percent of high-income respondents and only 3 percent of low-income earners blame monetary policy. Overall, 18 percent of respondents blamed Biden and 10 percent blamed "greed," but low-income respondents are far more likely to blame the president (22 percent of them do) than high-income earners (12 percent) are.

Fears about the consequences of inflation also extend beyond the economic realm and into metapolitics. Close to three-quarters of all respondents in Stantcheva's survey say inflation will hurt America's international reputation and will decrease political stability at home. Those types of worries can become self-fulfilling—or can give voters an incentive to embrace radical alternatives.

Having a large number of people angry about their declining living standard, even (or perhaps especially) if they don't fully understand the underlying cause, seems like a formula for broader discontent. History, and Stantcheva's research, suggests many people will be looking for someone to blame.

For large sections of the electorate, immigrants seem to be a likely scapegoat. An annual Gallup survey released in July showed that 55 percent of Americans want to see immigration to the U.S. decreased. For decades, that figure had been gradually declining, and the inflection point lines up almost exactly with the acceleration of inflation. In May 2020, Gallup found just 28 percent of Americans favored less immigration. That number climbed to 38 percent in 2022, 41 percent in 2023, and then jumped again in 2024.

Certainly, anti-immigrant political rhetoric has been a feature of right-wing politics since well before the current bout of higher inflation. Gallup's numbers suggest something has changed in the past four years, however, and that argument is now connecting with a much larger audience.

"Without fully understanding inflation's monetary roots, we can all mistake the symptoms for its cause," says Ryan Bourne, a Cato Institute economist who edited the recent book The War on Prices.

Bourne says "unexpected inflation creates conflict" and warns that frustration about inflation can lead to "blaming malevolent actors or external forces, and moralizing about people's self-interested behavior."

Though the contours of those conflicts have differed throughout history, it seems unwise for officials to ignore the ways that ongoing higher-than-normal inflation can stress our already overheated political system. If you want to safeguard democracy, one of the top agenda items should be limiting inflation.

Unfortunately, that has not been at the top of the agenda.

Who Gets the Blame?

It's only fair to pause for a moment and point out that no one actively chose this result.

Presidents are not singularly responsible for everything that happens to the economy while they are in office. There is no toggle switch on the side of the Resolute desk to increase inflation or wages, just as there is no button for low gas prices or full employment. This has always been true, under Biden and Trump and all who came before them, and it will be true when someone new gets to the Oval Office.

And yet, both Trump and Biden must bear some responsibility for all this. At nearly every turn, the two most recent presidents repeatedly made choices that heightened the risk of accelerating inflation. Once the risk materialized, Biden has taken steps to worsen it, Trump has promised to pursue similar measures, and both have sought to stoke popular discontent for political gain. Neither seems to have much in the way of a solution.

Start with Trump. In just four years, he oversaw more than $8 trillion in new borrowing. In doing so, he and his fellow Republicans didn't just reveal that their Obama-era criticism of high spending was unserious. They also ignored a pile of economic evidence that large debt-to-GDP ratios tend to nudge inflation higher, and to make it harder to control once it hits.

When COVID-19 arrived, Trump pushed for and signed two multitrillion-dollar spending bills that included a number of items likely to increase inflation—such as direct payments distributed to many American households regardless of whether they'd suffered any economic hardship from the pandemic.

Then came Biden. Not long after taking office in January 2021, his administration made a choice to pursue what Bloomberg termed "run-it-hot economics," which included the $1.9 trillion American Rescue Plan and the distribution of another round of stimulus checks. Although some economists, like Summers, warned that more borrowing risked tipping the economy into an inflationary cycle, the White House had significant support in mainstream, liberal institutions for cranking the spigot wider. Neil Irwin, then The New York Times' senior economics correspondent, wrote that the most important lesson for the incoming administration was the fact that "a 'hot' economy with high deficits didn't cause runaway inflation."

And then it did.

Now What?

When inflation peaked at various other times in American history, Binder says, the political system has struggled to respond. The same has happened in the past few years.

"We saw the Biden administration blaming inflation on [Vladimir] Putin and corporate greed, because they didn't want tighter monetary policy that might risk a recession or higher unemployment," she says. She also notes that issues that frequently popped up during inflationary periods in the 19th century have returned. The political right wants to hike tariffs. The left is focused on using antitrust laws to break up big businesses and somehow combat greed itself.

None of that is likely to lower inflation in a meaningful way, because of course it is a monetary phenomenon—thank you, Milton Friedman. But waiting for inflation to ease on its own or substituting the squeeze of higher prices for the pinch of higher interest rates is not a satisfying solution for most people. The voters demand that the politicians do something, and those who want to get reelected feel the urge to try.

That's what is missing in Stantcheva's survey, says Binder, who reviewed the paper before it was published. "Even though people report disliking inflation on her survey, they often do like, and push for, policies that are inflationary—like expansionary monetary policy (low interest rates) and fiscal stimulus," Binder says.

Officials should resist calls for inflationary policies in the middle of an inflationary period. Unfortunately, inflation breaks people's brains—and politicians are people too.

Inflation is one of the defining factors of the election season. Biden's "run-it-hot economics" was the fulfillment of a campaign promise to deliver more stimulus—and to send more checks to American households, a policy idea that unsurprisingly polled extremely well when it was tried during the pandemic. When that was no longer tenable, Biden and Congress passed the Inflation Reduction Act, which hiked spending on a variety of lefty priorities such as green energy subsidies and taxpayer-funded health care. Analysts at the Penn Wharton Budget Model calculated that the bill would marginally increase inflation over the next decade rather than, well, reduce it.

Trump, meanwhile, has responded to popular anger about inflation by calling for more tariffs and for reducing the Federal Reserve's political independence. Binder says that's a mistake. When inflation unleashes anger that the political process channels into dubious quick fixes, that's exactly why an independent central bank with a price stability mandate matters.

"If we left it to elected officials, there would always be excessive pressure for inflationary policies," she says. "The Fed often has to take actions that are politically unpopular in the short run to preserve price stability in the longer run."

Since the 1980s, inflation control has been one of the Fed's core responsibilities. Regardless of what other problems libertarians might have with the central bank, it's difficult to argue that it didn't do a decent job of keeping inflation low for several decades. Keep in mind: One of the reasons people seem to be so bothered by inflation rates between 3 percent and 4 percent is that inflation averaged well below 2 percent for so long.

"Inflation, once out of control, lasts a few years. This fosters the idea that technocratic institutions like the Fed just aren't very good at their jobs and don't have control. Having called inflation 'transitory' and said it would be over in months adds to this," says Bourne. But politicizing the Federal Reserve and giving presidents more control over interest rates "would be way worse," he adds.

Instead, elected officials in the legislative and executive branches should focus on what they can control. Excessive spending that relies on multitrillion-dollar deficits (much of which is financed by the Federal Reserve's willingness to buy Treasury bonds) makes inflation more likely in the future—and more difficult to contain in the present. If democracy is poorly equipped to deal with inflation, that's ultimately an argument for why America's leaders must resist the siren calls of stimulus spending in the first place. Once unleashed, inflation is difficult to tame and will unpredictably disrupt social and political cohesion, leading to yet more poor policy.

There may be no easy way out. In a letter to shareholders in early April, JPMorgan Chase CEO Jamie Dimon warned of "ongoing concerns about persistent inflationary pressures." Dimon, one of the world's most influential bankers, urged his shareholders and employees to prepare for a lengthy battle against higher prices, no matter what the official inflation stats say each month.

"Today there is tremendous interest in monthly inflation data, although it seems to me that every long-term trend I see increases inflation relative to the last 20 years," he wrote. "Huge fiscal spending, the trillions needed each year for the green economy, the remilitarization of the world and the restructuring of global trade—all are inflationary."

Søren Kierkegaard, the 19th century philosopher whom Biden has a penchant for quoting in stump speeches, once wrote that there are two ways to be fooled. "One is to believe what isn't true, and the other is to refuse to believe what is."

When it comes to inflation, our political leaders seem guilty of both errors. For the better part of two decades, politicians in both parties have acted like inflation had been permanently tamed, that low interest rates meant that borrowing was cheap and easy, and that it appeared there would be no consequences for soaring deficits. This was not true.

Now both candidates for president seem to refuse to see what is true. Inflation is not a passing or transitory concern, and it is not a problem to be solved with bumper-sticker talking points or by scapegoating it away. America's ongoing battle with inflation is the story of the 2024 election, and it may very well be the story of 2025 and 2026 too. It should serve as a warning for the next generation of political leaders: Unleash this monster at your own risk.

Show Comments (180)