The Man Who Hated Rules

Hacktivist-journalist Barrett Brown sets out to settle scores in his new memoir.

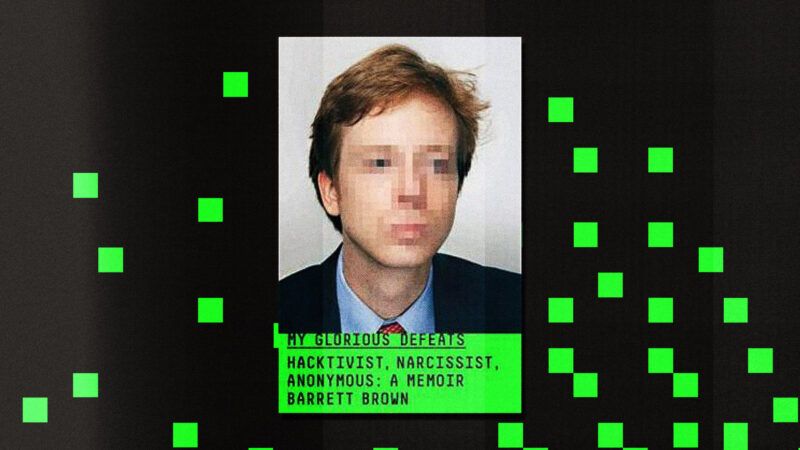

My Glorious Defeats: Hacktivist, Narcissist, Anonymous, by Barrett Brown, MCD, 416 pages, $30

Seven years after his release from federal prison, Barrett Brown has published a memoir recounting his time in the company of the hacker group Anonymous and his time behind bars, as well as an updated list of every person he now despises. Lest followers of the social media star turned transparency martyr think they've heard all this before, My Glorious Defeats: Hacktivist, Narcissist, Anonymous digs deeper into Brown's psyche than anything he's divulged before.

To wit: "The institution of bed-makery was among the first clues I'd encountered as a child that the society I'd been born into was a haphazard and psychotic thing against which I must wage eternal war."

My Glorious Defeats sometimes reads like H.L. Mencken and Emma Goldman had a baby and raised it on Ritalin and the Leroy Jenkins meme. Requiring someone to fold his bedsheets "within an inch-based margin of error," as Brown and other prisoners were made to do at Federal Correctional Institution Fort Worth, "is inherently totalitarian." If making the bed did "serve some benefit to one's character," he writes elsewhere, "then the U.S. military, among which this tradition reaches its deranged pinnacle, would be pumping out brigade after brigade of hyper-enlightened scholar-knights rather than the sort of people who scream at me about where I put my cup."

There is more to this book than artful screeds against hospital corners, but at the same time, there is not. A journalist who embedded with Anonymous and was eventually convicted of hacking-related offenses after his compatriots infiltrated the servers of a private security firm called Stratfor, Brown stalks his past with the safety off and a duffle full of magazines.

He starts his tale in 2006, when, at the tender age of 26, he submersed himself in the primordial goo of the shithead internet: the message boards 4chan and 7chan and the trolling-and-memes wiki Encyclopedia Dramatica. Brown saw these communities wreak incredible havoc when members coalesced around a target, and he "became obsessed with the question of what would happen when these people realized what they were capable of."

The first sign came in 2008, with Anonymous's campaign against the Church of Scientology, which was working to suppress a leaked video featuring the actor and church member Tom Cruise gushing over the group's most secret and sacred theology. The church's efforts to remove the video using the Digital Millennium Copyright Act as a cudgel angered some 4chan village elders, who maintained their own server. In November 2008, this 4chan offshoot posted an ominous video on YouTube titled A Message to Scientology, in which a digital voice promised to "expel you from the internet and systematically dismantle the Church of Scientology in its present form." The video made national headlines and prompted protesters in Guy Fawkes masks to congregate outside Scientology buildings around the world.

In 2010, Anonymous hacked hundreds of Australian government servers to stop the passage of an internet censorship law. Shortly thereafter, an article in The Huffington Post "revealed an unusual degree of understanding of Anonymous." The author, of course, was Brown, who speculated in the piece that Anonymous might usurp "the institution of the nation-state" as the "most fundamental and relevant method of human organization."

The chief architect of the anti-Scientology campaign brought Brown into the group's inner circle, where Brown made himself useful in the only way he knew how: flakking for hackers.

A reasonable person might conclude that Brown came to serve as a spokesperson for Anonymous, given that he endeared himself to the people who organized the movement, strategized with them regularly in public and private channels, carried their water on cable news, and pushed other journalists to highlight their exploits. Yet Brown has rejected this label for years by insisting that Anonymous could not be led or spoken for. Thus, anyone who identified him as a spox was a clueless media normie, a corrupt media normie, or a vile pig looking to deprive Brown of his freedom. The only exception is Brown, who cops in his book to regularly introducing himself at "talks and conferences" by "listing a series of mutually exclusive characterizations" that have appeared in media reports about him.

"As to the truth on these and other matters," goes Brown's standard talk, "I'm going to play coy for now, as whatever else I may be, I'm definitely something of a coquette."

Brown is so resistant to external governance that he cannot distinguish between unprincipled behavior (like the surveillance and reputation-wrecking activities of the security firms hacked by his compatriots) and illegal behavior (the hacking itself). This boundary-blindness led Brown to assist the hackers of Stratfor in ways that exposed him to prosecution; when his and his mother's homes were raided, that boundary-blindness led him to post an unhinged video on YouTube in which he threatened to ruin the life of an FBI agent.

That video led to his arrest. In the protracted battle with federal prosecutors that followed, Brown's amorphous relationship with Anonymous and his own revolutionary rhetoric were used to put him in prison.

Brown's life story might read a little differently if he did not seem to believe that any rule he chooses to break shouldn't exist, whether it's Second Life's policy against harassing other players, a federal prison's prohibition on narcotics, or British laws on "alarm and distress," which Brown was convicted of violating in November 2021 after he furnished a banner reading "Kill Cops" at a London rally.

Then again, his extraordinary tolerance for the consequences of his insolence is also Brown's greatest asset. Brown served his pretrial and post-conviction sentence at several facilities, and he seems to have made his way into the special housing unit at every stop—often for nonviolently flaunting rules, but sometimes only for telling his captors that he knew his rights better than they did.

Many white-collar offenders in Brown's shoes would've kept their heads down and their mouths shut, but he is the civil disobedience equivalent of a Jackass character, throwing himself into the maws of the state without regard for how bad things might get. Like the heavily scarred and toothless regulars of the Jackass franchise, Brown seems significantly worse for wear after 14 years in the burn-it-all-down movement. And yet, he still can't stop prevaricating.

Upon being contacted by the Dallas Observer for a comment on his conviction in England, Brown responded that "the English are an obnoxious and tiresome people that we should have finished off after we were done with Germany." He then applied for asylum in the United Kingdom, which the Brits denied in February 2024.

Reading the final chapters of his memoir is like channel-flipping through basic cable in the middle of a workday: Everyone is trash. J.R.R. Tolkien, Bob Woodward, Julian Assange, a long list of cable news anchors, bloggers, and middle and upper managers in the private surveillance industry—all, in Brown's estimation, just trash.

Brown has been settling some of these scores for over a decade. To what end? In one inadvertently clarifying passage, Brown sarcastically notes that he "had a few run-ins with the law" and "I have since been employed largely in documenting and redocumenting that story in order to present certain truths about our civilization and point the way toward solutions to the problems described, and also to be entertaining because people enjoy that."

My Glorious Defeats is undoubtedly entertaining. But the solutions appear to have been cut for space.

Show Comments (10)