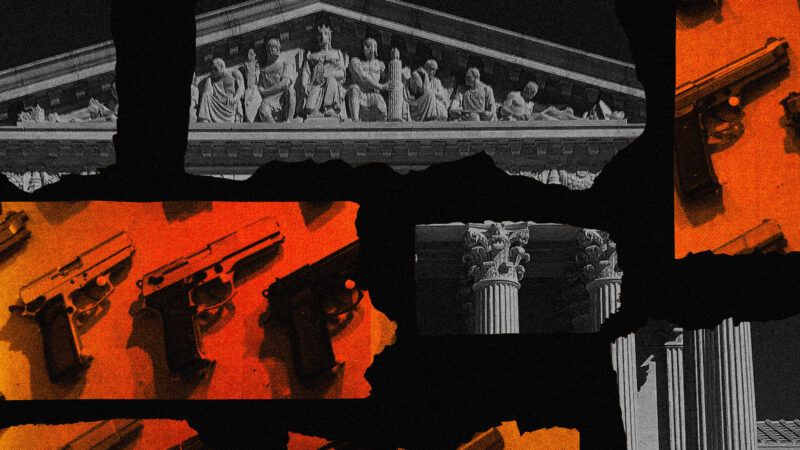

The Supreme Court Isn't as Radical as You Think

There is a great deal of panic surrounding the "extreme" nature of the current Court. But that is often not based in reality.

Last Friday, activist Shannon Watts took to social media to respond to the Supreme Court's 8–1 ruling in U.S. v. Rahimi, in which the justices ruled it is legal for the government to temporarily disarm someone whom a court has found poses a safety threat to others. "The Rahimi case should never have been taken up by SCOTUS," she said in a now-deleted post on X, formerly Twitter. "To even question whether domestic abusers should have access to guns shows just how extreme this court has become."

It was an odd thing to say, for a few reasons. For one, the decision, by pretty much all accounts, was a victory for Watts: She is the founder of Moms Demand Action, a gun control advocacy group. Even more puzzlingly, the Supreme Court's ruling overturned a decision from the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 5th Circuit, so if the justices had not taken up the case, they would have left intact a decision that prohibited the government from enforcing bans on gun ownership for people Watts strongly believes should not have access to firearms.

But the story here isn't that an activist said something head-scratching. The story is that Watts, while making little sense, actually managed to make total sense, against the wider backdrop of the panic associated with the current makeup of the Supreme Court.

It's worth asking how we got here. Such panic isn't necessarily new. But since the end of former President Donald Trump's administration, with his final appointment of Justice Amy Coney Barrett, it has crescendoed more dramatically than the most tortured Tchaikovsky symphony. And that's a high bar.

The conservative majority is both extreme and radical, we sometimes hear, and the ideological fracturing couldn't be starker. People are, of course, entitled to their views about the various decisions the Supreme Court issues; at some point, at least one is (understandably) bound to let you down. But what gets lost in that news cycle is that the justices agree a lot of the time.

The decisions at the beginning of this term, for example, laid the ground for something historic. (And it was historic unity, not division.) Of the 18 rulings released from December to April this term, 15 of them were unanimous, which, according to Adam Feldman—previously the statistics editor at SCOTUSblog—is the most unified the Court has been at the start of a term in modern history.

But what about those infamous 6–3 splits, where the Court breaks along partisan lines? There are indeed many 6–3 rulings. What almost never makes the news, however, is that the majority of such decisions released thus far this term have not fallen on the standard party-line divide. Instead, they've been composed of unorthodox alliances that challenge the notion that evaluating the law is exclusively an ideological task. That's a rich story, but it's one that's rarely told.

You don't have to look very far to find an example. Last week, for instance, I wrote about Erlinger v. United States, in which the Court strengthened the right to trial by jury and to due process in criminal sentencing. It's an issue that, on its face, likely has more cultural currency with left-leaning folks. And yet Justice Neil Gorsuch's opinion for the 6–3 ruling was joined not only by Chief Justice John Roberts, Justice Clarence Thomas, and Justice Amy Coney Barrett but also by Justices Sonia Sotomayor and Elena Kagan. The dissenters: Justices Brett Kavanaugh, Samuel Alito, and…Ketanji Brown Jackson.

That does not negate the fact that there are very consequential rulings that do come down along ideological lines. The Court's 2022 decision in Dobbs v. Jackson Women's Health Organization—overturning Roe v. Wade and concluding that the Constitution does not confer the right to an abortion—likely epitomizes that for many. It is definitely a part of the story.

But the misguided and pervasive belief that it is the entire story is how you get coverage and comments like the one from Watts, or from MSNBC host Chris Hayes, who said Friday shortly after the release of the Rahimi decision that "the stakes of a Trump second term is him having an opportunity to turn the Supreme Court into the Fifth Circuit." His comment was similarly odd, particularly when considering that the ruling, again, explicitly reversed a 5th Circuit decision. Eight of the nine justices, including all of Trump's appointees, voted in the majority.

None of those justices are beyond reproach or critique. People will continue to find justifiable reasons to object to their jurisprudence. But this fearmongering in a moment when basic reality belied the case for doing so reminds us of how manufactured this panic can be.

Show Comments (39)