Federal Government Will Borrow Another $20 Trillion in the Next Decade

Three things to know about the new Congressional Budget Office report on the growing federal deficit.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the federal deficit surged to unprecedented, barely fathomable levels: more than $3.1 trillion in 2020 and $2.7 trillion in 2021.

The federal deficit will soon approach those huge figures once more—not due to one-time emergency spending in response to a crisis, but simply the result of the government's routine operation.

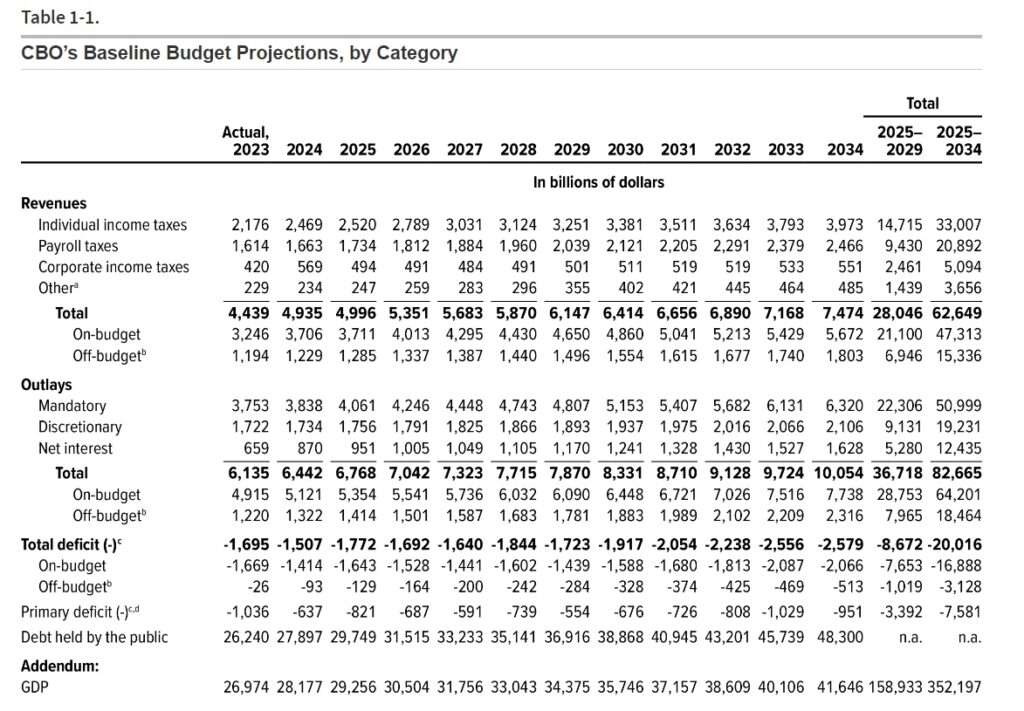

In a new semi-annual forecast released Wednesday, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projected that the federal government's annual budget deficit will exceed $2.5 trillion by 2034 if current policies remain in place (and assuming no further emergency spending of any kind, which seems like a stretch). The federal government is on pace to borrow more than $20 trillion over the next 10 years, the CBO estimates.

Here are three key things to know about the new CBO report. First, it demonstrates how too much borrowing in the past will affect the future.

A huge factor driving deficits over the next decade will be rising interest payments on the $34 trillion (and rapidly growing) national debt. As recently as 2021, interest costs on the debt totaled about $350 billion, but that line item is now growing thanks to higher interest rates. The CBO expects interest costs to total $860 billion this year—exceeding military spending—and to reach $1.6 trillion by 2034. At that point, more than a quarter of all federal tax revenue will be directed toward paying the interest on the debt.

"That's 3 months of your federal taxes each year that will not fund a single veteran, Social Security benefit, or highway expansion," Brian Riedl, a senior fellow at the conservative Manhattan Institute and a former Senate budget staffer, wrote on X (formerly Twitter). "What a waste."

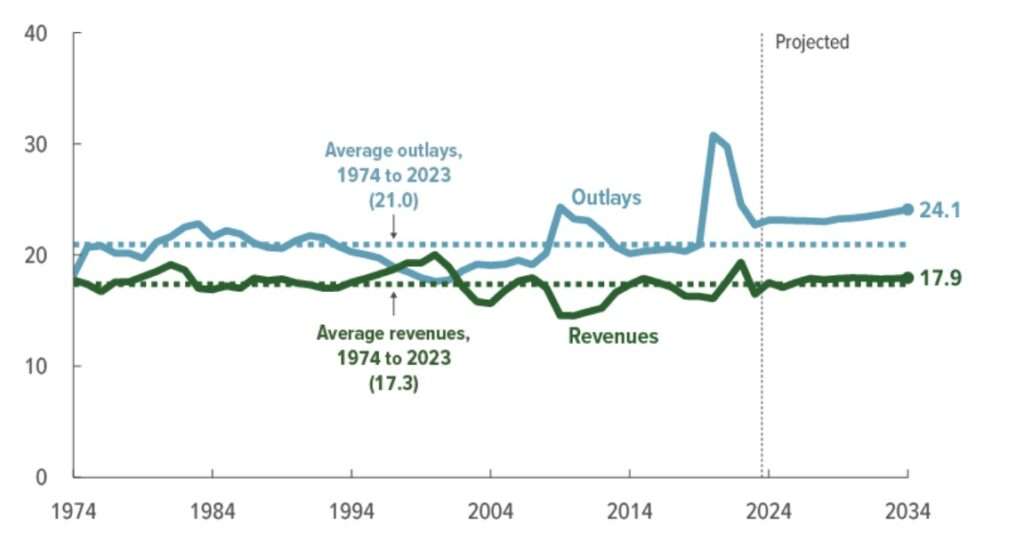

Second, the CBO projections make clear that the federal government has a spending problem, not a revenue problem.

A budget deficit is the gap between how much the government collects in tax revenue and how much it spends during a single year. When deficits are expected to grow over a period of years, that means spending is rising faster than expected revenue, or revenue is falling relative to planned spending, or both. In the federal budget, it is clearly the former.

Measured as a share of the economy as a whole, federal tax revenue has historically averaged about 17.3 percent. This year, the CBO expects about 17.5 percent of America's gross domestic product (GDP) to be vacuumed up by the federal government, and over the next 10 years tax collections will average about 17.8 percent of GDP. That's slightly above average, but the problem is that federal spending is expected to grow much faster—and into territory well outside of historical norms.

Finally, we should remember that the actual fiscal situation is likely to be worse than what the CBO is projecting—despite what the White House is saying.

The Biden administration greeted the CBO's new projections as an encouraging sign, pointing out that the estimates show a slightly lower deficit for this year than the CBO had previously expected.

But it is important to keep in mind that the CBO's projections look exclusively at current policies and therefore assume that, among other things, the Trump tax cuts will not be extended beyond their planned expiration in 2025. It also does not account for the possibility of another major emergency, or even a relatively mild recession. "The primary deficits in CBO's projections are especially large given the relatively low unemployment rates that the agency is forecasting," the CBO notes.

As Riedl highlighted on X, a more realistic alternative scenario in which the tax cuts are extended and discretionary spending caps are not maintained results in deficits that will exceed $3 trillion by 2030.

In short: Those pandemic-era deficits won't look like outliers for very long.

Show Comments (33)