'Someone Is Going To Die Today': Did Daniel Penny Act in Self-Defense?

"I have encountered many things," one witness told the grand jury, "but nothing that put fear into me like that."

In January 1985, Sol Wachtler, then the newly minted chief judge of the New York Court of Appeals, commented to The New York Daily News that prosecutors in his state could "by and large" get grand juries to "indict a ham sandwich."

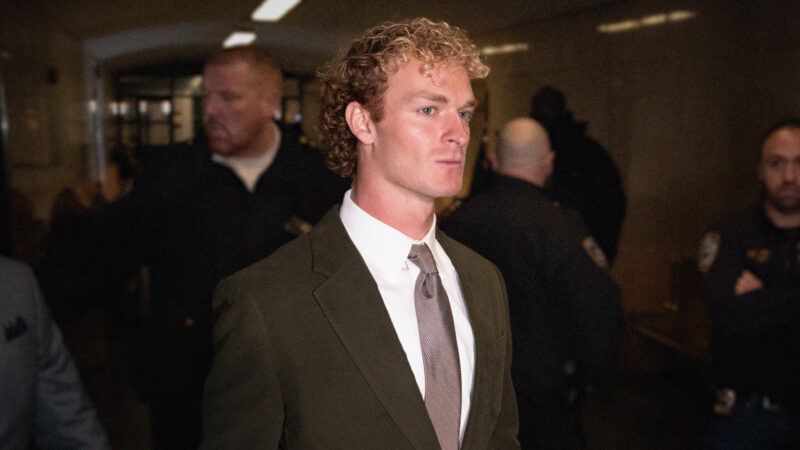

To date, the ham sandwiches have remained free. But the spirit of the maxim—that district attorneys can usually secure an indictment regardless of a case's merits—has likely attracted some modern-day supporters with the prosecution of Daniel Penny, whom a grand jury indicted on second-degree manslaughter and criminally negligent homicide charges in June. This week, a judge rejected Penny's motion to have those charges dismissed.

On May 1, 2023, a man named Jordan Neely began threatening passengers in a New York subway car. Penny, a former Marine, responded by restraining Neely in a chokehold. Police boarded the car several minutes later, and, after attempting CPR, Neely was transported to Lenox Hill Hospital, where he was ultimately pronounced dead.

The case almost immediately became a cultural litmus test for how you feel about crime, homelessness, and the right to self-defense. Is Daniel Penny a reckless vigilante? Or is he a ham sandwich?

Testimony given to the grand jury, provided by witnesses on that subway car, injects a bit more nuance into a debate that has primarily been colored by a viral video taken by a freelance journalist who'd been on the train.

"Someone is going to die today," Neely reportedly said, according to Person No. 9, a high school student who testified she started to pray that the "doors would open" so she and her classmate could get away. Neely threatened that he "would kill anyone" and was willing to "take a bullet," said Person No. 4, a retiree. Two more witnesses added that Neely had assumed a fighting stance, and another witness—Person No. 18, a mom who was taking her young son to a therapy appointment—recounted that Neely was making "half-lunge movements" and coming within "a half a foot of people."

"I have been riding the subway for many years," said the retiree. "I have encountered many things, but nothing that put fear into me like that."

On the flip side, the video, taken by journalist Juan Alberto Vazquez, captures a passenger telling Penny he might "catch a murder charge" if he continued because he had a "hell of a chokehold." "My wife is ex-military," he said. "You're going to kill him now."

Much has been made of the fact that Penny is also a veteran. He should've known when to release Neely, the thinking goes.

Not necessarily, according to several Marine veterans interviewed by Business Insider, all of whom said that training focuses not on the safety of a subject but on the safety of innocent bystanders whose lives may be in danger. "Once you make the decision to intervene, the only thing you can do is hold on until help arrives," said a former senior officer, who opted to remain anonymous. "We don't place a heavy emphasis on knowing when to let up to ensure your opponent survives," added Alex Hollings, a former Marine black belt who of the four was the most critical of Penny's actions. "He should have been able to assess that his opponent was no longer providing any kind of resistance, and at that point he should have known that Neely was unconscious," he said. "Of course, we are talking about a fight. Most people aren't thinking at all, let alone thinking straight during one."

It will be up to a jury now to determine if the alleged recklessness Hollings describes rises to a criminal level. And reckless will indeed be the key word. Under New York law, Penny is guilty of second-degree manslaughter if he "recklessly cause[d] the death of" Neely despite being "aware of and consciously disregard[ing] a substantial and unjustifiable risk that such result will occur." [Emphasis mine.] For the criminally negligent homicide charge, Penny is guilty if he caused Neely's death after he "fail[ed] to perceive a substantial and unjustifiable risk that such result will occur." [Emphasis mine.] The former charge carries a prison sentence of up to 15 years; the latter count prescribes a term of up to four years.

Those who feel Penny's prosecution is unjust—that he has been ham-sandwiched—can take comfort in the fact that his jury at trial will be tasked with evaluating his case with a much higher standard of proof than his grand jury was. That may not be complete consolation, however, when considering another criminal justice cliche: that "the process is the punishment."

Show Comments (128)