How The Simpsons Strangled Itself Into Irrelevance

The once-subversive show now traffics in the clichés it used to mock so effectively.

To paraphrase Marx, sitcoms repeat themselves, first as satire and then as farce. Or maybe just as self-parody.

That's the case with The Simpsons, America's longest-running scripted TV series, longest-running animated show, and longest-running sitcom. Once an engagingly genial yet subversive part of American popular culture whose creator, Matt Groening, sharpened his talents in alternative comix, The Simpsons soldiers on in its 35th season as a pale, tired imitation of its earlier self, one that no longer delights as much as it disappoints. It is almost certainly asking too much for The Simpsons or any other creative offering to keep a sharp edge for this long, but the show's latest controversy provides an object lesson in how pedantic and tedious American culture can become.

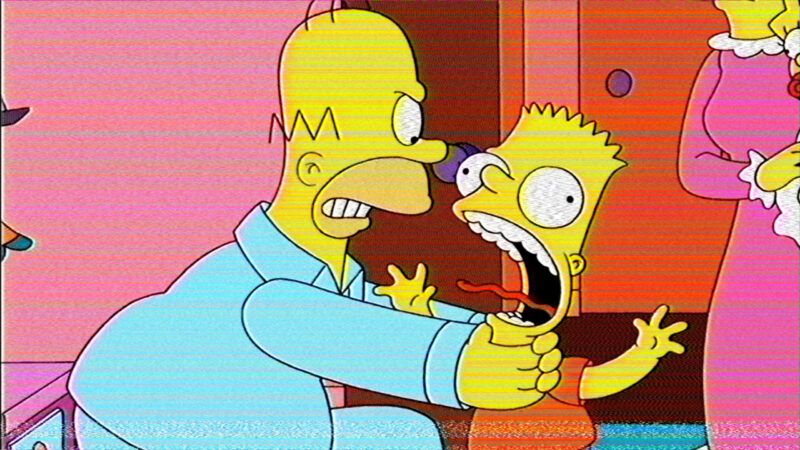

In a recent episode, goofball patriarch Homer announces that he will no longer enact one of the show's longest-running gags, which involved strangling his son Bart whenever the kid pisses him off (which is often). When meeting a new neighbor who remarks on his strong handshake, Homer says to his wife, "See, Marge, strangling the boy has paid off….Just kidding. I don't do that anymore….Times have changed!" As the pop-culture site IGN notes, Homer hasn't in fact strangled Bart onscreen since the 2019–2020 season. (Go here for a supercut video that promises "Homer STRANGLING Bart For 10 Minutes Straight!")

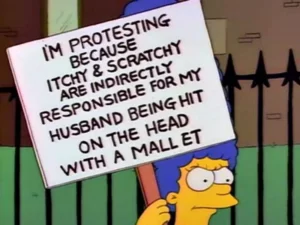

Yes, times have changed. The minute I read about the new episode, I thought back to a particularly memorable installment from the show's second season. In "Itchy & Scratchy & Marge," Marge leads a successful campaign to clean up TV after realizing how ultra-violent her kids' favorite cartoon, Itchy & Scratchy, really is. (In a typical episode, "Field of Screams," Itchy the mouse runs over Scratchy the cat with a thresher and then uses the decapitated head to play catch with his son, parodying a scene in the syrupy baseball movie Field of Dreams.)

The inciting incident for Marge comes when baby Maggie imitates what she sees on the small screen and whacks Homer on the head with a mallet. Marge's protest succeeds spectacularly, and she gets the makers of Itchy & Scratchy, whose theme song promises "They fight! And bite! They fight and bite and fight! Fight, fight, fight! Bite, bite, bite!" to create wholesome episodes like the one below, titled "Porch Pals":

The new and improved Itchy & Scratchy is so nauseatingly sweet and good-for-you that Springfield's kids turn off their TVs and go outside to play and start to thrive like never before, a wry commentary on persistent fears that fantasy violence—and fantasy sex—on the boob tube deformed children's moral lives.

In its earlier days, The Simpsons wasn't simply funny. Along with a number of other shows, such as Beavis and Butt-head and Mystery Science Theater 3000, it helped to teach us all how to consume pop culture critically by commenting directly and indirectly on the recurring conceits and tropes of TV and the critical discussion about the medium.

This was no small matter. The country was in the midst of an explosion of cultural offerings that freaked out tastemakers and gatekeepers. As the double whammy of cable TV and the internet rolled out across the nation, powerful people were convinced that most of us, but especially children, were incapable of distinguishing between basic cable and basic reality. What we needed more than ever was a guardian class that would regulate and restrict the music we listened to, the TV and movies watched, and the websites we searched. As the University of Tulsa's Joli Jensen told Reason, the guardian-class attitude proceeds from "an assumption that art is an instrument like medicine or a toxin that can be injected into us and transform us." If you believe that, you are going to do whatever you can to make sure only the "right" sort of messages are being sent. "Just like TV sets or radios," I summarized the view in 1996, "we are dumb receivers that simply transmit whatever is broadcast to us. We do not look at movie screens; we are movie screens, and Hollywood merely projects morality—good, bad, or indifferent—onto us."

That sort of thinking has a long and storied lineage, and it has been applied in various ways to novels, movies, comic books, rock and roll, and other forms of mass entertainment. The idea regularly migrates to new forms of popular culture (video games, social media, smart phones) and usually gets dressed up in scientific-sounding language.

It's hard to recapture the moral and social panic caused by the appearance of The Simpsons and the Fox network on which it appeared. Fox became the fourth over-the-air broadcast network in late 1986 and was known for its edgy content and gross-out humor. Conservatives and liberals alike attacked The Simpsons and the network's other shows, such as Married…with Children, as portents of the end of all that was good and decent in American society. Bluenoses raged at the sight of Bart wearing a t-shirt with "Underachiever" emblazoned on it, with some school districts actually banning the gear. Republican Bill Bennett and Democrat Joe Lieberman, two thankfully mostly forgotten but once powerful political figures, joined forces to denounce such anti-social offerings by handing out "Silver Sewer Awards" that trashed Fox TV and Rupert Murdoch for vulgarizing the airwaves. They were joined by such figures as Sen. Bob Dole (R–Kansas), Attorney General Janet Reno, and first lady Hillary Clinton, who were convinced that "fantasy violence" and promiscuous sex scenes on TV caused those same problems in the real world. Reno explicitly threatened TV networks with censorship, averring that "the regulation of violence is constitutionally permissible" while senators pushed legislation that would have made cable networks subject to FCC content regulations. Pundits predicted an endless rise in mayhem if shows like The Simpsons—which had a famous gag where a character kept shouting "Will someone please think of the children?"—weren't reined in.

Such fears mostly dispersed in the absence of plausible research showing much of a correlation, much less anything hinting at causation, between watching sex and violence on TV and then perpetrating it in the real world. The long and virtually uninterrupted decline in crime that began in the mid-1990s—right as increasingly violent and sexually explicit TV, internet content, and video games were becoming ubiquitous—also helped to minimize calls for more G-rated content and tighter restrictions on who could consume what. Which of course isn't to say they went away: In 2005, for instance, Hillary Clinton, by then a senator from New York, declared that the video game Grand Theft Auto "encourages [children] to have sex with prostitutes and then murder them" while calling for an federal investigation of how games were rated and sold.

Over the past decade or so, calls for kinder, gentler content seem driven less by worries that, say, depictions of violence will cause problems in the real world and more about the pain and suffering that bad representations of particular types of characters might cause among some viewers. Indeed, the last time The Simpsons was widely discussed was in 2017, when comedian Hari Kondabolu* called out the show for its supposedly one-dimensional representation of South Asians in the documentary The Problem with Apu. As a result, the actor who voiced Kwik-E-Mart owner Apu, Hank Azaria, stopped doing the character. A few years later, during riots and protests in the wake of the police killing of George Floyd, the producers of The Simpsons announced that it would "no longer have white actors voice non-white characters."

However well-intentioned such gestures might be, it's clear that they have done nothing to bring viewers back to The Simpsons. In its first few seasons, it averaged well over 20 million viewers per episode. Its most recent complete season drew less than a tenth of that.

"Itchy & Scratchy & Marge" ends with Marge renouncing paternalistic censorship after a movement inspired by her own activism launches a campaign to put pants on Michelangelo's David. Thirty-three years later, the show that once challenged the censorial zeitgeist now seems all too much a part of it.

CORRECTION: This article originally misidentified the writer and star of The Problem with Apu as Akaash Singh, whose 2022 comedy special Bring Back Apu argues that The Simpsons character "is not racist, he's the American Dream."

Show Comments (77)