Biden Is Pandering to the 1 Percent: Union Manufacturing Workers

Less than 1 percent of American workers are union members in manufacturing jobs. But you'd never know that by watching our politics.

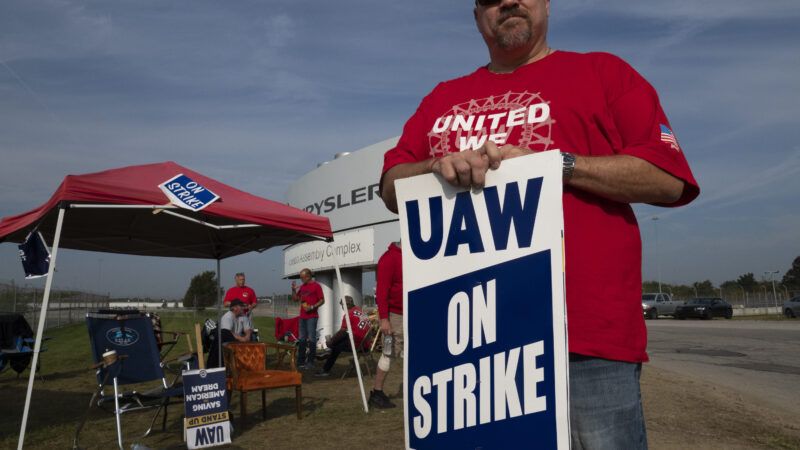

President Joe Biden plans to travel to Michigan on Tuesday, where he will speak in support of striking autoworkers and become the first American president to walk a picket line.

It's too soon to tell whether Biden's support will have much of an effect on the impasse between the so-called Big Three automakers (Ford, General Motors, and Stellantis, the international conglomerate that owns the remnants of Chrysler) and the United Auto Workers (UAW), the union that called the strike earlier this month. Politically, however, the White House is framing the event as the ultimate show of solidarity from the pro-union president.

You might also think about it as something else: Joe Biden's stand for the 1 percent.

That's roughly the percentage of the American workforce that is unionized and employed in manufacturing. Far from being a broad-based signal of support for blue-collar Americans, Biden's advocacy on behalf of the UAW this week will be performative shilling for a mere sliver of the country's workers.

In fact, it's actually less than 1 percent, as Middlebury College political science professor Gary Winslett pointed out on Twitter last week. According to Bureau of Labor Statistics data, about 7.8 percent of American workers are employed in manufacturing jobs, and about 8 percent of manufacturing workers are members of a union. Put those figures together, and the result is that only about 0.62 percent (or roughly 842,000) of America's 135 million workers fit into both categories.

"If the American labor force were visualized as 500 workers, only 3 of them fit this image," Winslett helpfully explains.

That's a useful way of illustrating one of the biggest disconnects between reality and our political rhetoric—which continues to equate the interests of unions with the interests of working-class Americans, even though unionization rates have been falling for decades.

These days, there are roughly seven times as many unionized workers in the public sector as there are in manufacturing jobs. That means unions are far more likely to represent the interests of bureaucrats and public school teachers than grunts on the assembly line.

To some extent, that reflects the overall decline in manufacturing jobs since the labor unions' heyday of the mid-20th century, of course. But that's not all. It also demonstrates how manufacturing work has shifted toward places with low rates of unionization. South Carolina, Tennessee, and Alabama have become America's new hotbed for auto manufacturing, but most of those workers aren't part of the UAW—though there is one auto plant in Alabama that's part of the current strike.

There is no indication that the working public wants more union representation. When asked, most workers indicate they have little interest in joining a union. In a Gallup poll published last year, just 11 percent of nonunion workers said they were "extremely interested" in getting organized. Meanwhile, 58 percent said they were "not interested at all" in joining a union.

But that same poll also indicates why Biden—and, for that matter, former President Donald Trump, who is also making public displays of affection towards the UAW—is rushing to join the striking autoworkers in Michigan. According to Gallup, 71 percent of Americans have a favorable opinion of labor unions, the highest rating since 1965.

It's a bit of a political conundrum. Only a sliver of blue-collar workers are members of unions, most workers have little interest in joining unions, and so it should be no surprise that most new manufacturing jobs are in nonunion shops. Yet even as unions have dwindled as an economic force in America's manufacturing sector, they've enjoyed a surge in political support from voters who at least like the idea of labor unions even if they've got little interest in actually joining one.

We've effectively romanticized the idea of what a labor union is. It's similar in some ways to how the public has nostalgic and generally positive views regarding train travel, even though only 22 million people (well less than 10 percent of the country) rode Amtrak last year. Most of us wouldn't choose to join a labor union or travel by train, but we like the idea of both things existing.

And as long as unions are giving off good political vibes, politicians with abysmal approval ratings will be falling over one another to be associated with those romantic notions. Biden's (and Trump's) appearance in Michigan this week is more like a religious pilgrimage than a serious commentary on the state of organized labor in the American economy.

And even though Biden has a First Amendment right to say and do whatever he'd like in this situation, it's pretty unseemly to have the country's chief executive picking sides in what is ultimately a private dispute between the automakers and their workers. There's a good reason why presidents have never done this sort of thing before.

Biden and his political advisers are surely convinced that the show of solidarity is important for his reelection campaign. "The president's plans come as some Democrats have begun to question his response to the strike, recognizing that he needs the full backing of union workers in his presidential reelection bid," is how Politico described the machinations last week.

That may very well be true, but this is a moment where political truth might bear little resemblance to reality. Unionized manufacturing workers are a tiny sliver of the American economy, but it seems that pandering to their demands is more politically important than ever.

Show Comments (46)