America's Immigrant Brain Drain

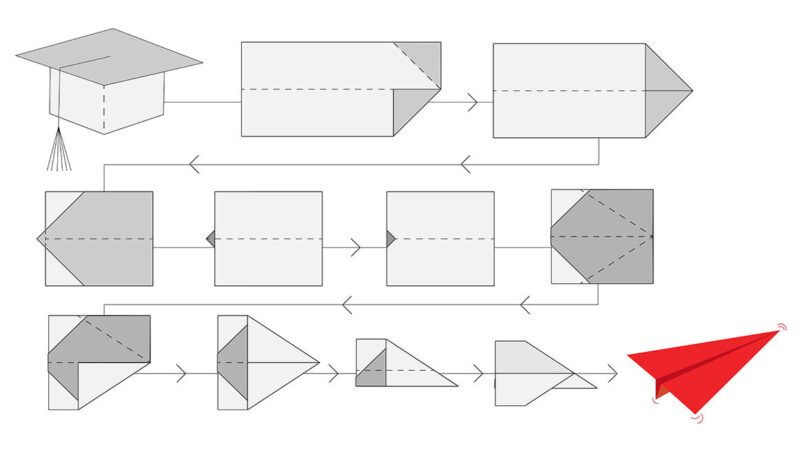

International students want to stay in the U.S. after graduation. Most of them can't.

The United States boasts more international students, immigrant inventors, and foreign-born Nobel laureates than any other country. But thanks to our dysfunctional immigration system, the U.S. is slowly surrendering that advantage to other countries.

In June, The Hechinger Report outlined how foreign governments are welcoming U.S.-trained international students. The United Kingdom offers a "high potential individual" visa, which authorizes a two-year stay and is available to "new graduates of 40 universities….21 of them in the United States." Recruiters from Australia are "attending job fairs and visiting university campuses" in the United States. From 2017 to 2021, according to the Niskanen Center, a Washington-based think tank, Canada managed to attract almost 40,000 foreign-born graduates of American universities.

Most international students want to stay in the U.S. after graduating, but very few are able to do so. The U.S. does not have a dedicated postgraduate work visa. Canada and Australia, meanwhile, have streamlined the steps from graduation to employment to permanent residency. Graduates in the U.S. can complete Optional Practical Training, but it does not lead to permanent residency and lasts a maximum of three years.

Worryingly, fewer international students are choosing to study in the U.S. in the first place, in part due to COVID-related border closures and the Trump administration's hostility toward international students. Although international student enrollment is creeping back toward pre-pandemic levels, the number of Chinese students, who make up the biggest share of foreign students in the U.S., has declined.

Many foreigners who graduate from American universities try their luck with H-1B visas, which are reserved for skilled workers. But there are problems with this pathway, both in design and in practice. Demand for H-1Bs far outpaces supply, and the annual cap of 85,000 visas has not changed in more than 15 years. Three-quarters of America's H-1B workers are Indian. But thanks to caps on the number of green cards a given country's nationals can receive each year, there is a massive backlog of workers waiting for permanent residency. It can take decades for Indians to achieve that status.

Canada recognizes that this work force is both valuable and frustrated with the U.S. system. In June, the Canadian government announced a "Tech Talent Strategy" that, among other things, will create a pathway for "H-1B specialty occupation visa holders in the US to apply for a Canadian work permit." It will also offer work and study permits to family members.

It is not just foreign workers who suffer under the U.S. immigration system. American employers are increasingly unwilling to navigate such complex processes to hire foreigners, depriving them of employees who might otherwise be perfect fits. Envoy Global, an immigration services provider, reported in March that 82 percent of the employers it surveyed "had to let go of foreign employees in the past year due to difficulties securing or extending an employment-based visa in the U.S." A similar share transferred foreign workers to an office abroad for similar reasons. And a staggering 93 percent of the businesses that Envoy surveyed said they were considering nearshoring or offshoring.

Until the U.S. gets out of its own way, talented foreigners will look for more welcoming pastures. Our loss will be other countries' gain.

Show Comments (84)