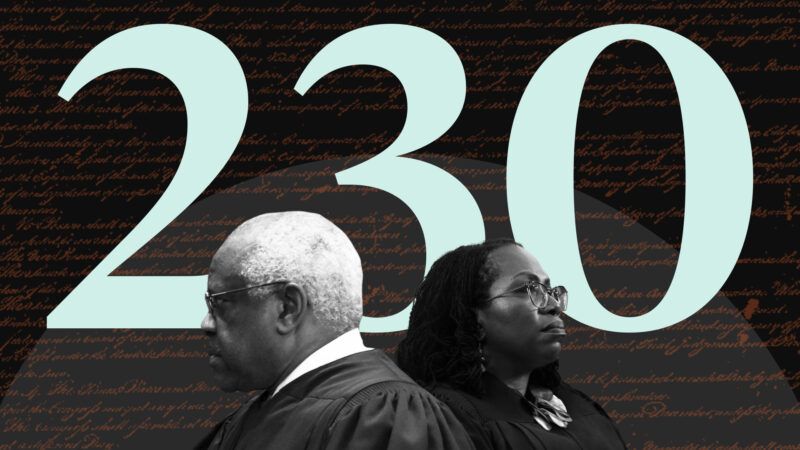

Is Ketanji Brown Jackson a Greater Threat to Big Tech Than Clarence Thomas?

The Supreme Court’s newest member weighs in on the meaning of Section 230 in Gonzalez v. Google.

Justice Clarence Thomas has emerged in recent years as the Supreme Court's biggest critic of Big Tech. Like many modern conservatives, Thomas seems to believe both that social media companies routinely censor conservative viewpoints and that the government should do something about it. Thomas has even spelled out his own preferred vision of how the government might more aggressively regulate social media platforms.

That was the Thomas I expected to hear from today when I tuned in to the oral arguments in Gonzalez v. Google, one of the most significant Big Tech cases on the Supreme Court's docket in recent years. To my surprise, however, Thomas seemed quite skeptical about some of the key arguments made against Google. "I don't understand how a neutral suggestion [by YouTube] about something that you've expressed an interest in is aiding and abetting," he declared at one point. "I don't understand it." Google's lawyers were undoubtedly happy to hear that.

At the same time, those lawyers were surely less than thrilled by the statements of the Court's newest member, Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson, who seemed to be Google's biggest enemy on the bench. Is she now a greater judicial threat to Big Tech than Thomas?

At issue in Gonzalez v. Google is whether Google, which owns YouTube, is immunized from lawsuits alleging that YouTube's algorithms aided terrorists by recommending Islamic State videos to users. The legal dispute centers on the famous Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act of 1996, which says, "no provider or user of an interactive computer service shall be treated as the publisher or speaker of any information provided by another information content provider."

It should be an easy case. As the Reason Foundation, the nonprofit that publishes this website, noted in an amicus brief, "the plain text of Section 230 precludes claims that would treat YouTube as the publisher of videos created by third parties solely because YouTube uses an algorithm that organizes and presents the videos of its users to others who might be interested in them."

Yet that plain text did not stop Justice Jackson from raising a drastically different reading of Section 230. "Isn't it true that the statute [Section 230] had a more narrow scope of immunity than…what YouTube is arguing here today," Jackson said to Google's lawyer, Lisa Blatt, "and that it really was just about making sure that your platform and other platforms weren't disincentivized to block and screen and remove offensive content? And so to the extent the question today is, well, can we be sued for making recommendations, that's just not something the statute was directed to."

In other words, under the reading of Section 230 that Jackson was asking about, YouTube might not receive any Section 230 protections from being sued over its algorithmic recommendations to users. What's more, under that same reading, the same would likely also be the case for a bedrock internet function like Google search, which also algorithmically recommends third-party content to users. If the Section 230 interpretation that Jackson sketched out was ever endorsed by a majority of the Supreme Court, it would unleash a torrent of litigation and, in all likelihood, wreck the internet as we know it.

Show Comments (151)