Trump's Lawyers Say It's Not Clear Whether 'Purported' Classified Documents at Mar-a-Lago 'Remain Classified'

The former president's legal team notably did not endorse his claim that he automatically declassified everything he took with him.

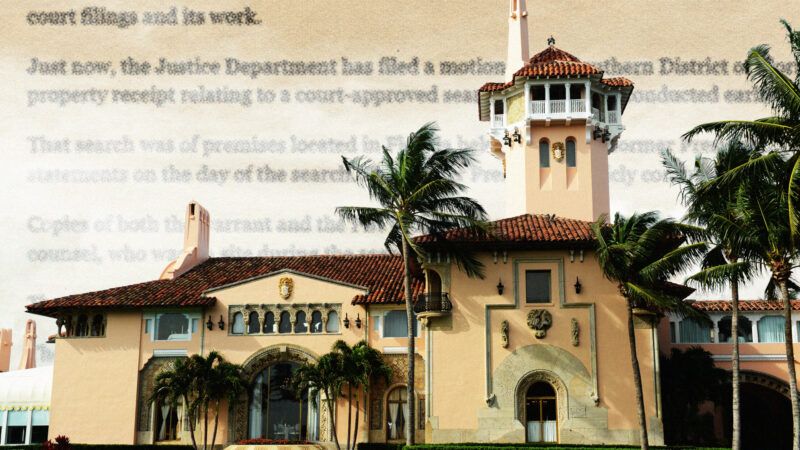

The Justice Department says more than 100 documents that the FBI seized during its August 8 search of Mar-a-Lago, former President Donald Trump's home and private club in Palm Beach, were marked as classified. Notwithstanding those markings, Trump insists, none of the records were actually classified, because he had a "standing order" as president that automatically declassified documents he removed from the Oval Office to study at his residence in the White House. "The very fact that these documents were present at Mar-a-Lago," he said four days after the search, "means they couldn't have been classified."

In a brief they filed today in the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of Florida, Trump's lawyers notably do not endorse that argument. But they do claim that the status of the "purported 'classified records'" seized by the FBI is a matter of dispute. "The Government has not proven these records remain classified," they say. "That issue is to be determined later."

Trump and the Justice Department are wrangling over the terms of an order that U.S. District Judge Aileen M. Cannon issued last week. Cannon agreed with Trump that a neutral arbiter known as a "special master" should be appointed to review all the material seized at Mar-a-Lago. The special master is supposed to determine which documents might be protected by attorney-client privilege or, more controversially, executive privilege. In the meantime, Cannon said, the FBI may not use the documents to investigate whether Trump or his representatives committed federal felonies by improperly retaining and concealing the records.

Cannon's order allows intelligence agencies to continue a review aimed at determining whether and to what extent Trump's retention of the documents compromised national security. But in a motion filed last Thursday, federal prosecutors argued that her order would interfere with that process, which "cannot be readily segregated" from the criminal investigation. They asked Cannon for a partial stay allowing the FBI to continue examining the documents marked as classified, which represent a small subset of some 13,000 items removed from Mar-a-Lago. Failing that, they said, the government "intends to seek relief" from the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 11th Circuit.

Responding to that motion today, Trump lawyers Christopher Kise, Lindsey Halligan, Evan Corcoran, and James Trusty say the government's concerns "appear exaggerated." They distinguish between the intelligence review, which seeks to determine "potential damage to national security from allegedly mishandling classified information," and the FBI's probe, which focuses on "criminal repercussions for allegedly mishandling classified information." They argue that the former can proceed even if the latter is suspended.

At the same time, Kise et al. question the premise underlying both processes. "The Government's stance assumes that if a document has a classification marking, it remains classified irrespective of any actions taken during President Trump's term in office," they say. "The Government claims this Court cannot enjoin use of the documents the Government has determined are classified. Therefore, the argument goes, as President Trump has no right to have the documents returned to him—because the Government has unilaterally determined they are classified—the Government should be permitted to continue to use them, in conjunction with the intelligence communities, to build criminal case against him. However, there still remains a disagreement as to the classification status of the documents."

That stance marks a shift from the position that Corcoran took in a May 25 letter to Jay Bratt, chief of the Counterintelligence and Export Control Section in the Justice Department's National Security Division. At that point, Corcoran was referring to documents "purportedly marked as classified." Now he admits the documents were in fact "marked as classified" while remaining agnostic about the significance of those labels.

Kise et al. note that "the President enjoys absolute authority…to declassify any information," and "there is no legitimate contention that the Chief Executive's

declassification of documents requires approval of bureaucratic components of the

executive branch." But unlike Trump, his lawyers do not claim he used that authority to declassify everything he took with him when he left the White House. Trump has presented no documentation of the "standing order" he supposedly issued, which was news to national security officials who should have known about it.

The documents marked as classified, which ranged from "confidential" to "top secret," included "sensitive compartmented information" on subjects such as human intelligence sources. Last week The Washington Post, citing "people familiar with the matter," reported that the records included information about a foreign nation's nuclear capabilities. The Post added that "some of the seized documents detail top-secret U.S. operations so closely guarded that many senior national security officials are kept in the dark about them."

By Trump's account, he nevertheless decided that the documents were not sensitive enough to keep them classified. Yet the automatic declassification he describes did not hinge on whether exposing the information would jeopardize national security. According to Trump, it applied to anything he happened to remove from the Oval Office. It also clearly did not entail changing the labels on the documents so that government employees would know how to handle and store them.

William Barr, Trump's former attorney general, thinks it is "highly improbable" that Trump had such a policy. But if he did, Barr told Fox News, it would have been remarkably careless: "If in fact he sort of stood over scores of boxes, not really knowing what was in them, and said, 'I hereby declassify everything in here,' that would be such an abuse and show such recklessness that it's almost worse than taking the documents."

Trump's lawyers do not even mention his purported "standing order," let alone delve into its implications. But as they see it, the FBI's investigation "at its core is a document storage dispute that has spiraled out of control." Instead of simply seeking to ensure that the "purported 'classified records'" were properly secured, they complain, "the Government wrongfully seeks to criminalize the possession by the 45th President of his own Presidential and personal records."

That gloss elides a couple of important points. Under federal law, those presidential records, classified or not, were not "his own." Contrary to what Trump seemed to think, they belonged in the National Archives. For a year and a half, Trump resisted efforts to recover the documents. He gave 15 boxes, including 184 documents marked as classified, to the National Archives in January, a year after leaving office. Last June, Corcoran and Christina Bobb, another Trump lawyer, handed over an additional 38 classified documents in response to a federal subpoena, at which point they assured the Justice Department that no more remained at Mar-a-Lago. Yet the FBI discovered more than 100 during its search.

In Krise et al.'s telling, that was no big deal. "There is no indication any purported 'classified records' were disclosed to anyone," they say. "Indeed, it appears such 'classified records,' along with the other seized materials, were principally located in storage boxes in a locked room at Mar-a-Lago, a secure, controlled access compound utilized regularly to conduct the official business of the United States during the Trump Presidency, which to this day is monitored by the United States Secret Service."

Unlike Trump, who still insists that he actually won reelection in 2020, his lawyers at least concede that his presidency ended in January 2021. But they seem to be implying that he retained some prerogatives of that office, including the authority to keep "purported 'classified records'" at the resort where he used to conduct presidential business.

Back in May, Corcoran told Bratt that documents "purportedly marked as classified" were "once in the White House and unknowingly included among the boxes brought to Mar-a-Lago by the movers." That description hardly inspires confidence about Trump's care in handling sensitive information. Nor does it seem consistent with his claim that he deliberately declassified everything. How can that be true if he did not even realize what was in the boxes, which included material that was "unknowingly" moved to Mar-a-Lago? And if there was nothing wrong with keeping the records, in what sense was taking them a mistake?

Although the documents were "principally located" in "a locked room at Mar-a-Lago," the FBI reportedly was alarmed by security camera video showing people removing material from that room. According to the Justice Department, the FBI's search discovered dozens of records with classification markings in other locations, including desk drawers and "a container" in Trump's office. The Post notes that the FBI also found "dozens of empty folders marked classified."

Those details suggest that the concerns underlying what Kise et al. describe as a "document storage dispute" may have been perfectly reasonable. That does not necessarily mean the threat to national security was grave and imminent enough to justify the unprecedented and politically explosive decision to search a former president's home. The intelligence review may or may not substantiate that claim. But based on what we know so far, the government's fears do not seem frivolous.

Despite Trump's focus on the issue, the three possible crimes cited in the FBI's search warrant do not hinge on whether the documents were still classified. The obstruction statute covers conduct aimed at interfering with a federal investigation. The law dealing with improper retention of government documents applies to unclassified as well as classified material. Even the Espionage Act provision cited by the FBI does not mention classification, referring instead to "defense information" that "could be used to the injury of the United States or to the advantage of any foreign nation."

If the Justice Department decided to prosecute Trump on any of those charges, it might have trouble proving the requisite intent. But even if Trump's conduct can plausibly be attributed to some combination of ignorance, arrogance, laziness, and sloppiness, it should give pause to Republicans who were still inclined to support him.

Show Comments (184)