Supreme Court Says High School Coach's Postgame Prayers Are Protected Free Speech

A 6–3 majority sees it as noncoercive and not a violation of the Establishment Clause.

The Supreme Court ruled today that a high school football coach has a First Amendment right to lead a voluntary postgame prayer on the field and that a school district cannot punish him for it.

In a 6–3 decision, the Court determined that Joseph Kennedy, a former assistant coach at Bremerton High School in Washington state, was within his First Amendment rights and not acting in his capacity as a school official when he prayed on the 50-yard line at football games and permitted others (including students) to join him. As such, Kennedy was not causing the school to violate the Establishment Clause and endorse a particular religion.

The majority decision for Kennedy v. Bremerton School District, written by Justice Neil Gorsuch and joined by Chief Justice John Roberts and Justices Samuel Alito, Clarence Thomas, Amy Coney Barrett, and Brett Kavanaugh, leans heavily on evidence and statements that no student was coerced or ever said they felt coerced to participate in these postgame prayers. Gorsuch observes that it doesn't appear that the method that Kennedy engaged in prayer caused anybody to feel as though he were pushing his religion on students as a coach:

This Court has long recognized as well that "secondary school students are mature enough … to understand that a school does not endorse," let alone coerce them to participate in, "speech that it merely permits on a nondiscriminatory basis." … Of course, some will take offense to certain forms of speech or prayer they are sure to encounter in a society where those activities enjoy such robust constitutional protection. But "[o]ffense … does not equate to coercion."

Gorsuch rejects the idea that "any visible religious conduct by a teacher or coach should be deemed—without more and as a matter of law—impermissibly coercive on students" as "a sure sign that our Establishment Clause jurisprudence had gone off the rails." He argues that such a position isn't neutral at all. It would preference secular speech and repress religious speech, a violation of the First Amendment. He sees this case differently from other examples—like a member of a church reciting a prayer during a graduation speech or a school broadcasting a prayer over a public address system prior to a football game. Those were examples where the school was making religious expression a part of an event. Courts have seen this as an impermissible violation of the Establishment Clause. That's not what happened in this case.

That's how the majority sees the facts. But the dissenters in this case, justices Sonia Sotomayor, Elena Kagan, and Stephen Breyer, see the very details of what happened here differently from how Gorsuch presents them in the majority opinion. Gorsuch's opinion presents Kennedy as "engaging in a brief, quiet, personal religious observance." Sotomayor, who wrote the dissent, writes that this characterization is wrong, and Gorsuch's description essentially downplays any potential coercive impacts of the prayer:

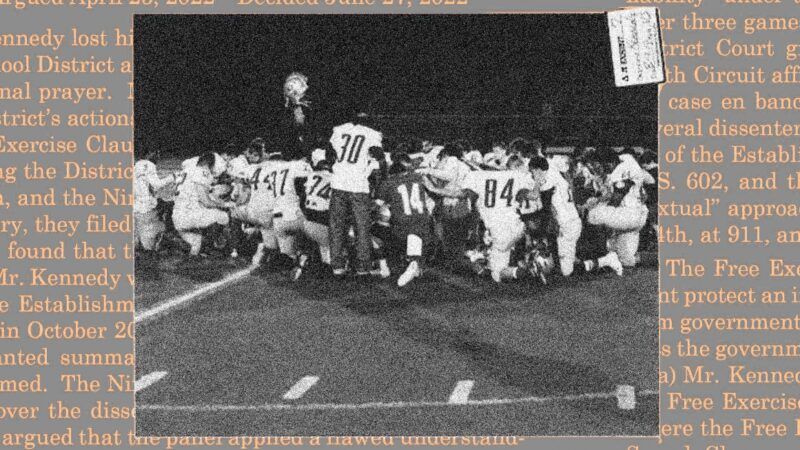

To the degree the Court portrays petitioner Joseph Kennedy's prayers as private and quiet, it misconstrues the facts. The record reveals that Kennedy had a longstanding practice of conducting demonstrative prayers on the 50-yard line of the football field. Kennedy consistently invited others to join his prayers and for years led student athletes in prayer at the same time and location. The Court ignores this history.

Sotomayor's dissent includes actual embedded photographs of the prayers on the 50-yard line with the coach surrounded by players, showing that this isn't some quiet personal observance. He sought out media coverage for his prayers. The school district noted that despite Kennedy's insistence that he wasn't inviting others to pray with him, he had, in fact, done so on many previous occasions. The school district's messaging to Kennedy was consistent in that it held no objection to his religious beliefs or even to him praying while on duty as long as it didn't interfere with his job or suggest that the school endorsed his religion. In short, it seemed as though the school district was genuinely concerned that Kennedy's behavior would be seen as a violation of the Establishment Clause if they didn't clearly communicate established limits on what Kennedy was allowed to do.

She notes that Kennedy ignored attempts by the school district to try to come to some accommodation and instead turned to the press and made a big spectacle out of the prayers. Parents told the school district that their children participated in the prayers "solely to avoid separating themselves from the rest of the team."

Sotomayor sees a constitutional violation in this case, but it's not Kennedy's rights that were violated:

Properly understood, this case is not about the limits on an individual's ability to engage in private prayer at work. This case is about whether a school district is required to allow one of its employees to incorporate a public, communicative display of the employee's personal religious beliefs into a school event, where that display is recognizable as part of a longstanding practice of the employee ministering religion to students as the public watched. A school district is not required to permit such conduct; in fact, the Establishment Clause prohibits it from doing so.

In a way, the dramatic difference in the interpretation of the events is an example of the longstanding challenges in determining how to navigate what does and does not count as a government establishment of religion vs. private expression. It's extraordinary that both the majority and the minority opinion in this case believe that a First Amendment violation occurred here. But the majority sees Kennedy as the victim and the minority sees him as the cause.

It turns out that a lesser-noticed Supreme Court verdict from May held a sneak preview of what Gorsuch would be discussing in the majority opinion. In that case, Shurtleff v. Boston, the Supreme Court ruled unanimously that the City of Boston erred when it told a Christian group they couldn't participate in a program to fly their flag on the grounds of City Hall. In that case, it was clear that the flag program did not constitute an official endorsement by the city. By forbidding a religious group from participating, the city was discriminating against religion, not taking a neutral stance.

That decision against Boston was unanimous, but Gorsuch wrote a separate concurrence laying the blame for this conflict on a past Supreme Court decision, Lemon v. Kurtzman. That case from 1971 led to what has been called "the Lemon test," a three-pronged set of guidelines that were intended to help determine whether a government policy entangled the church with the state.

Gorsuch noted in the Shurtleff ruling that the Lemon test had instead introduced more chaos and caused more problems than it solved. The Boston case was telling because the city genuinely believed that it had to forbid the Christian group's flag or else the city would be violating the Establishment Clause. And yet, the city was wrong.

In today's case, the evidence is fairly clear that the school district wasn't anti-Christian—it genuinely believed it would be violating the Establishment Clause if they didn't put a stop to Kennedy's behavior. Three justices agreed with the school district.

Today's ruling replaces the Lemon test, which Gorsuch notes has frequently been ignored or criticized in previous rulings. Instead, the Court instructs that the Establishment Clause "must be interpreted by 'reference to historical practices and understandings'" and to set the line between what is and is not allowed to "accor[d] with history and faithfully reflec[t] the understanding of the Founding Fathers." These instructions draw from another court decision, Town of Greece v. Galloway, where the Supreme Court justices ruled, 5–4, that the town of Greece, New York, wasn't violating the Establishment Clause by opening meetings with a prayer from a volunteer chaplain.

It's not clear why Gorsuch thinks guidelines from a 5–4 decision in 2014 that asks people to interpret what the Founding Fathers would have wanted are going to cause less chaos than the Lemon test. Sotomayor's dissent worries that, in fact, abandoning the Lemon test is going to make the problem even worse:

Today's decision is particularly misguided because it elevates the religious rights of a school official, who voluntarily accepted public employment and the limits that public employment entails, over those of his students, who are required to attend school and who this Court has long recognized are particularly vulnerable and deserving of protection. In doing so, the Court sets us further down a perilous path in forcing States to entangle themselves with religion, with all of our rights hanging in the balance. As much as the Court protests otherwise, today's decision is no victory for religious liberty.

Show Comments (224)