He Didn't Use the 'Magic Words' To Get Access to a Lawyer. Were His Rights Violated?

A recent court decision has reinvigorated the debate around just how specific the accused has to be in asking to speak with an attorney.

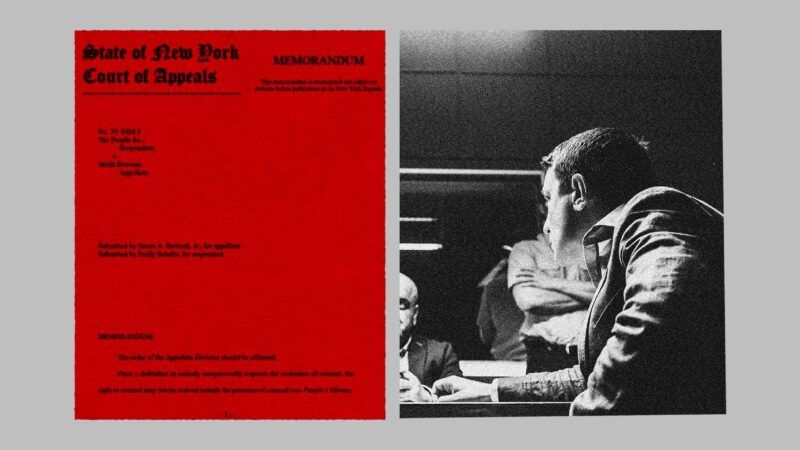

A teenager who asked to call his attorney but was denied the opportunity by police did not have his rights violated, the New York Court of Appeals ruled this week, reinvigorating a debate around what linguistic specificities are necessary to firmly and unequivocally invoke your Miranda rights.

In May 2016, Malik Dawson, then 19, was arrested for allegedly sexually assaulting a woman in Albany, New York, the week prior. When asked if he'd like to call his lawyer, the following exchange took place between Dawson and the detective:

Detective: Do you understand each of your rights?

Dawson: Yeah, definitely. I just wish that I'd memorized my lawyer's number. He's in my phone. Is it possible for me to like call him or something?

Detective: Do you want your lawyer here?

Dawson: Right now?

Detective: Yeah.

Dawson: If I could get a hold of him 'cause I don't know his number; it's in my phone.

Detective: OK.

Dawson: But you could still tell me what's going on though, right?

Detective: No, I can't talk to you if you if you want your lawyer here and you already said you did, so let's, you know what, let's give him a call.

But when the detective returned to the interrogation room, he came without Dawson's phone. Instead, he said: "Here's the deal, I'm just going to ask you flat out, because we're in the middle of this and this is something we could potentially resolve—do you want your lawyer here or do you want to just figure this out?" Dawson responded that he wanted to "figure this out."

As the detective began questioning Dawson about the alleged assault, Dawson insisted the encounter was consensual. The detective then told Dawson that if he were apologetic, it might work in his favor. So, without counsel present, he penned a letter to the victim admitting guilt and saying he was sorry.

Whether or not the detective violated the Constitution in demurring at Dawson's request for an attorney is the subject of the New York Court of Appeals' recent decision. "Here, there is support in the record for the lower courts' determination that defendant—whose inquiries and demeanor suggested a conditional interest in speaking with an attorney only if it would not otherwise delay his clearly-expressed wish to speak to the police—did not unequivocally invoke his right to counsel while in custody," the majority wrote.

Associate Judge Rowan D. Wilson dissented. "Here, Mr. Dawson unequivocally invoked his right to counsel—the record supports no other conclusion," he said. "As is clear from the quoted portion of the colloquy with the detective, he twice said he wanted to call his lawyer, and the detective twice expressly stated that he understood Mr. Dawson had asked to call counsel and therefore the detective could no longer speak to Mr. Dawson….An unequivocal request does not require 'magic words.'" (It is illegal for the government to continue questioning the accused after he has affirmatively invoked his desire for an attorney.)

This isn't the first time that granular language choices have been at the center of such disputes.

Consider the case of Warren Demesme, who told police in Louisiana that he wanted to speak to a "lawyer dog." He was not provided with one, and the Louisiana Supreme Court ruled that his rights were not violated because the request was too ambiguous.

That case, which was decided in 2017, got quite a bit of attention, with some deriding the absurd idea that any officer could have reasonably thought Demesme wanted to speak with a pet as opposed to an attorney. But even that decision was not so cut and dry. "Demesme obviously meant 'friend,' not the animal, and the police surely understood that. So if that's the criticism, it seems pretty fair," writes Orin Kerr, a law professor at the University of California, Berkeley, for the Volokh Conspiracy. "I think the ambiguity is not in the word 'dog' but in what Demesme said before that….On one hand, he did say 'give me a lawyer.' On the other hand, that phrase seems to have some conditions on it. He only wants a lawyer, he says, if the police think he did it."

In other words, whether or not someone has actually invoked their right to counsel is, to some degree, subjective, though it can have far-reaching consequences in a defendant's case. "The detective's statement that 'this is something we could potentially resolve' — after having confirmed Mr. Dawson's request to contact his counsel — is particularly concerning," wrote the dissenting judge in Dawson's case. "The statement implied that Mr. Dawson, if he were to abandon his right to counsel, might be able to very quickly settle the matter without issue. Of course, nothing could be farther from the reality." With the apology letter as evidence, Dawson was convicted and sentenced to seven years in prison, followed by 10 years of post-release supervision.

Editor's Note: As of February 29, 2024, commenting privileges on reason.com posts are limited to Reason Plus subscribers. Past commenters are grandfathered in for a temporary period. Subscribe here to preserve your ability to comment. Your Reason Plus subscription also gives you an ad-free version of reason.com, along with full access to the digital edition and archives of Reason magazine. We request that comments be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment and ban commenters for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

Malik Dawson, then 19, was arrested for allegedly sexually assaulting a woman in Albany, New York

Who does this clown think he is? The governor?

Ctrl+f: "please"

0/0

Case closed.

was Cuomo refused his lawyer?

If you ask me, the person under arrest should have to clearly and unambiguously decline to have an attorney present before questioning can happen without an attorney present. Any attempt to convince teh suspect to continue speaking without a lawyer should be presumed to be in bad faith and an attempt to trick people into not exercising their constitutional rights.

I don't know about your first statement, but could agree that "So, without counsel present, he penned a letter to the victim admitting guilt and saying he was sorry." should be inadmissible without it.

But until then and as usual, don't talk to the cops.

I'm sticking with it. The police's job is not to trick people into not exercising their rights. Their first loyalty should be to the constitution (ha, ha, I know). It's the foundational law of the land, not some inconvenient formality to work around.

Yeah but, particularly in a case like this, loyalty to Dawson's Constitution or the woman he allegedly assaulted. I think my compromise cuts both ways. If the lawyer's present for the confession, her right to be secure is still generally observed while still generally observing his right to due process without effectively hamstringing the law both/either way.

Per Diane Reynold's post below, agreed the 'dog' contest was bullshit, but who's to say when the police are tricking someone into not exercising their rights and when there is legitimate confusion and/or logistics issues and the suspect is racked with guilt or otherwise emotive? IMO, that's interpretive and the judicial is supposed to interpret.

I can see that. We should require definite rejection of council rather than affirmative request.

The problem is people want high conviction rates it seems. We have a strong emphasis on prosecutorial power because people like that.

I'm walking back what I said. It seems reasonable to require affirmative rejection of council, but I haven't really read up on that question.

But you're right, first and foremost people need to learn to shut the fuck up.

a professor once said to my class "only two words to ever say to a police: law. yer."

Every LEO I have ever worked with has said the same. Say nothing until you have spoken to a lawyer, then say nothing, let the lawyer say it.

I've got a better idea: no questioning without an attorney, even if the accused is too stupid to know he needs one.

-jcr

What you dee on TV is bullshit.

When arresting someone, they don't need their Miranda rights read to them.

The Miranda warning is only when the suspect - and the trigger for the warning is that the person is a suspect - is going to be questioned.

If you've had your rights read to you, YOU ARE A SUSPECT, and you should refuse to answer anything, without a lawyer present...who will tell you to not answer any questions.

It is lazy-man law enforcement to try to get a confession.

The cops need to go get evidence, not use what they can get a suspect to say.

If the police are talking to you you are a suspect until proven otherwise. They avoid reading Miranda rights by having a 'consenual' discussion. Never, never talk to cops without a lawyer.

Cops are trained to trick people in bad faith. It's their job.

Yep, and if that doesn't work, they just lie.

They lie anyway. Literally about everything. I think it's because their reports and testimony is considered to be The Word Of God in court, so they believe that they shape reality with their words.

He said he wanted to "figure it out" instead of talking to his lawyer.

Isn't it clear that cops can just wear you down with interrogation techniques until you give up on getting a lawyer? WHAT ARE YOU TRYING TO HIDE?

Warren Demesme, who told police in Louisiana that he wanted to speak to a "lawyer dog."

Yeah, pretty sure there should be a comma in there.

Even at that, the statement "Demesme obviously meant 'friend,'" doesn't help the confusion. 'Dude', 'man', 'pig', 'honky', 'jefe', 'boss', 'chief', 'ese'... the list of synonyms is long, but I wouldn't put 'friend' in there given the context.

Seems ridiculous to claim there was any confusion. They fucking knew what he meant. Or are too stupid to be employed even as cops.

But when the detective returned to the interrogation room, he came without Dawson's phone. Instead, he said: "Here's the deal, I'm just going to ask you flat out, because we're in the middle of this and this is something we could potentially resolve—do you want your lawyer here or do you want to just figure this out?" Dawson responded that he wanted to "figure this out."

Why did we leave the transcript and then go to explain the 'flavor' of the conversation?

Make no mistake, there's a LOT about this case that feels like bullshit:

But on the NARROW grounds that are before the judges "did he ask for his lawyer" my interpretation is yes, he did, then he rescinded that request which means "no, he did not ask for his lawyer."

I have no feeling on this case one way or another. But if I say to a cop, "I want to call my lawyer" and the cop says, "Are you sure?" and then I respond, "Naah, I was just yankin' your chain, I don't need to call my lawyer", then I didn't ask to call my lawyer.

Based on the "color" or "flavor" of the conversation, yes it seems ABUNDANTLY clear that the kid wanted to talk to his lawyer, then rescinded that request when given an opportunity to do so.

Is there possibly a case he was "coerced" into rescinding that request? Also, when you say "teenager", was he under 18 or over 18? If he was under 18, then I think a very good case could be made that he might have been coerced. If he was a "teenager" but was 19, then he's an adult and subject to an entirely different set of standards.

Malik Dawson, then 19, was arrested for allegedly sexually assaulting a woman in Albany, New York

Missed this on the first read-thru. So yeah, we don't get any of the soft-pedal considerations due a juvenile. So he's in the adult-hot-seat.

Again, there's a lot about how this case was handled from the interrogation standpoint. Perhaps whomever is running his case should focus on that.

My problem is the detective was not acting in good faith to get the lawyer to take care of this. If he'd brought the phone and pointed out how long he'd be here waiting I could see him rescinding the request. As it was the cop was yanking his chain and actively denying him access to counsel.

"But on the NARROW grounds that are before the judges "did he ask for his lawyer" my interpretation is yes, he did, then he rescinded that request which means "no, he did not ask for his lawyer.""

I have a different take. Once a suspect has asked for a lawyer, it ought to be completely and totally out of bounds for the cops to do anything in an attempt to get the suspect to revoke the request.

If the suspect were to revoke the request without the cops saying anything that might be different.

I have a different take. Once a suspect has asked for a lawyer, it ought to be completely and totally out of bounds for the cops to do anything in an attempt to get the suspect to revoke the request.

That's not unreasonable in my opinion. But I don't know anything in that is a part of settled law.

Again, I don't like how the general interrogation was handled. "Hey, man, just write a letter saying you're sorry and then it's resolved."

Fuck off with that shit.

Edwards v. Arizona (1981): "When an accused has invoked his right to have counsel present during custodial interrogation, a valid waiver of that right cannot be established by showing only that he responded to police-initiated interrogation after being again advised of his rights. An accused, such as petitioner, having expressed his desire to deal with the police only through counsel, is not subject to further interrogation until counsel has been made available to him, unless the accused has himself initiated further communication, exchanges, or conversations with the police." Because that interrogation was prohibited, the suspect's responses were inadmissible.

Agreed. If the suspect asks for a lawyer, continuing to ask questions about the case is out of bounds. "Are you really sure you want a lawyer" is in itself a question about the case.

I prefer my compromise above. Treat the confession like an affidavit. Have a lawyer there when it is signed. Then, like an affidavit, if the suspect/witness suffers cold feet, develops amnesia, disappears, or dies or whatever, the affidavit is still valid.

I prefer my compromise above. Treat the confession like an affidavit. Have a lawyer there when it is signed.

I actually kind of like this.

If the cops "trick" you into signing a confession, then at that point A lawyer must be present and talk to the accused beforehand to explain him what he's doing. If "the letter" is considered a confession by black-letter law, then that would fall under the doctrine.

I think it's pretty clear that the cop's intent was to get him talking without a lawyer. Once he asked for the lawyer, they should have stopped all attempts to question him.

Tricks like that really piss me off. Especially the "it will go better for you if you just do X" lies. They were just trying to trick him into a confession.

Even decades before 9/11, if you joked about hijacking a plane, the airport authorities were officially required to take you seriously, and to disregard any "hey, I was just joking!" claims. The same should apply here to I-wanna-lawyer statements, even if it cuts against the Authoritah of the cops and the power of Government Almighty, instead of in favor of it.

If a defendant asks for a lawyer, is it ok for the cops to deploy delaying and diversionary tactics until the defendants eventually gives up?

This seems problematic.

Once a lawyer is requested, rescinding the request should be not just voluntary but unsolicited.

it makes me so goddamn mad that police are legally allowed to play games like this and get away with it.

Lying to people.

Interrogating to the point of brain washing people into confessing to things they didn't do.

Throw DA's into the mix that without information and rarely get punished for it.

So many of these people in law are targeting number of wins and not number rightly brought to justice.

Another misconception from TV law enforcement.

The cops are in no position to make deals, or, as in this case, say how a letter, outlining the incident, even with an apology, is going to be used by the prosecutor.

The cops may have had every intention of the letter not being used as a confession, but they hold no sway over the prosecutor and would probably not want to go against him/her by testifying that it was their intention for this to settle the matter, amicably.

I understand that LEOs get lied to straight out of the gate, often on a daily basis, This being understood, this behavior on the part of more than a few of them is not helping them win hearts and minds. If police unions want to play the grievance card continuously, so be it, but they are partially to blame for the bad optics by defending behaviors like this.

It's not just the unions. All cops defend behaviors like this and worse. I say "all" because cops who do not are forced off the force.

Part of being a police officer is literally doing anything you want, because no one will stop you. Cops who stop other cops don't stay cops for long.

So many of these people in law are targeting number of wins and not number rightly brought to justice.

Power means never admitting to being wrong. That's why cops and DAs routinely prosecute people who they know to be innocent. They'd rather put an innocent person to death than risk people thinking they make mistakes.

There were several very good episodes of ‘The Practice’ around 20 years ago that highlighted these issues. It was a very underrated TV series.

I suppose it is easy to tell someone to lawyer up before talking to a cop. Maybe good advice for rich person or indigent. But someone who thinks he's done nothing wrong, or doesn't understand the law (everyone of us commits a crime every day) is going to try to talk his way out of it. "My lawyer" costs money - $100s per hour usually - so the temptation is to try to convince the cops to let you go rather than make a call to "my lawyer."

A very good point.

Unfortunately, it is how lawyers justify their usurious rates.

It ends up being more costly to try to save, when a lawyer is needed.

I can understand where they’re coming from. They want to get paid for their work. I’m not a lawyer, but I always have people that think I should be a pal and do a bunch of work pro bono. My brother in law’s younger brother was defrauded in a financial transaction that I advised him to walk away from. Then my brother in law comes back to me a year later and expected me to commit dozens, possibly over a hundred hours of my time to help his idiot brother out because he couldn’t afford retain an attorney. Which is what he needed at that point. Lawyers want to get paid, and so do I.

Agreed the cops should have handed him the phone when he asked for a lawyer and stopped the interrogation. However I'm very curious how a 19 year old has a lawyer, has his lawyer's number on his phone, maybe even on speed dial.

I didn't do anything that everyone else isn't doing. Once I explain that, they'll let me go. Right?

This is an atrocity.

And nothing will happen.

Does "Quiero un abogado" count?

Can we wait until the bureau of disinformation gives a ruling on the validity of this narrative before we form an opinion?

You can form any opinion you want.

Just don't say it out loud or on the web without approval from the Ministry of Truth.

That is until they perfect the mind reading chip and force all of us to have it implanted. How else can they root out wrong think completely?

I'm with the court on this one. "do you want your lawyer here or do you want to just figure this out?"

I don't know how much more clear the cop could have been. And this guy said figure it out.

Choice has consequences.

This one is tough, but I think once he asked (multiple times) for his lawyer, the cops should have made it happen before continuing the interview. I'm not sure they violated his rights so much as the cops' actions were underhanded.

They gave him a false choice.

An interrogation room is no place to "figure it out".

Because it went as far as an arrest and questioning, a report would have to be filed and it would be up to a prosecutor, whether the "figuring out" was sufficient to have the charges dropped, which it is clear, it wasn't.

The kid was naïve, and the cops knew better.

The false choice was "do you want to waive your right to a lawyer now, or should I ask again later?"

This is just additional proof that we need more dead cops, prosecutors, and judges.

Yes, everyone has a right to an attorney, but everyone has the right to not be sexually assaulted. Authorities are hired by the public to balance these rights. Law enforcers need to know the law, but they aren't qualified to give legal advice to every person that they deal with. If a suspect says he understands his rights, can't the investigator assume he understood them even if the suspect inadvertently confesses before a lawyer shows up?

The Miranda rights are rights, not mandates. Criminals, like all Americans, have a right to confess to crimes if they want to. I say Dawson's confession stands.

C'mon, man.

You think this kid - yes 19 is still a kid - thought what he did was going to be used as a confession?

He said it was a consensual encounter, that's not confessing to rape.

You seem to have difficulty comprehending 'alleged,' and how the justice system works; given the information presented, there is not much to indicate how the police got to him. Your emotional reaction to alleged sexual assault trumps one man's individual and civil rights, it appears.

It's a typical ploy. Cops will repeat a question, say "are you sure," ask leading questions, or just plain lie until they get what they want.

In this case it was very clear that the kid wanted a lawyer, but the cops played it until they got something that could be construed as a negative.

The case decision had a different description of events... defendant was administered his Miranda rights prior to being interviewed by the detective. The detective began the interview by reading the four parts of the warning and asked if defendant understood these rights. Although defendant stated, "yeah, definitely," defendant and the detective thereafter engaged in a colloquy, which included defendant indicating that he had an attorney – whose number was in his cell phone. However, when the detective asked defendant if he wanted his attorney present, defendant was vague, never responded affirmatively or negatively and instead stated, "I just really want to know what's going on." The detective informed defendant that he could not speak to defendant if he wanted his attorney to be present. The detective testified that at this point he was unsure if defendant wanted an attorney, so he left the interrogation room to speak to his supervisor and other detectives to determine how he should proceed. When the detective returned to the interrogation room, he repeatedly asked defendant if he wanted an attorney and each time defendant responded no. Whereupon the detective reread defendant his Miranda rights, and defendant stated that he understood them and wanted to speak to the detective. At no time did defendant request his counsel to be present and he acted in a manner consistent with a desire to fully and frankly cooperate in providing information to the detective

That brings up the concern expressed by "Diane Reynolds (Paul.)".

Why did we have a transcript-like rendering of the conversation, only to switch to a narrative?

The narrative in the case file could have been in the prosecution's pleading and not necessarily the real story.

This is why every interrogation needs to be video recorded, so that there can be no dispute as to what actually happened.

I suspect it was recorded because of the term "transcript." No recording means the court was relying on testimony, a report and notes. If you want to slant an article, you leave out facts. The district court would have heard the tape and would have heard the tone of the conversation. The appellate court would go off of the trial/hearing transcript and make a judgement based on that. Can't tell which transcript they are describing. There are a lot of reasons people talk to the police, including a belief that they can explain it away. In rape cases, it can make good sense to claim it was consensual which removes the DNA issue. Makes it a he said/she said case. It's a cop's job to get a statement if possible which, if nothing else, limits the ability for the defense to craft a better story later. If the cop went too far, then the statement is tossed. There is a balance.

It's almost like the detective deliberately sought to extract a waiver of his rights, and then extracted a confession.

Never talk to the police.

No exceptions.

Common misconception. Talk to a few cops. If you are guilty, definitely clam up until you can come up with a viable story. All cops will tell you that some people clear themselves simply by telling their side of the story. If a "victim" claims A and the "suspect" clams up, there is one story on the table and enough to book. If the suspect gives the cops enough to poke holes in the story, especially a false claim, then there will be no arrest. An alibi can eliminate you. It's one reason I have real issues with a rape claim from 3 years ago. Unless they give a specific date, how can the suspect credible say where he was or wasn't?

The problem with talking with cops is that they lie about literally everything. It's their job. They lie on reports. They lie in court. They lie to get people to say things. They lie about the law. Ask a cop for directions to the highway and they'll send you to the ghetto. I wouldn't trust a cop to give me the correct time. So it really is best to just shut up, because whatever you say will be misused by a professional liar.

Tricking a suspect into speaking or acting without requested lawyer present is not justice. It is a perversion of justice. If arrested, there is only one word you should say to the cops, and that word is, "Lawyer." That is the extent of your speech until you confer with counsel.

Thanks for your beyond belief blogs stuff. looking for a Accountant Bedford

It always amazes me that the lawyer union hasn't gotten us to the point where everyone arrested has to have a lawyer present all the time.

I read the memorandum opinion. Some two-bit law clerk wrote two paragraphs about the invocation of counsel not being unequivocal but rather only conditional on not delaying the discussion about what was going on and thus Edwards v. Arizona (or any New York case law equivalent) was inapplicable. Pure BS. Even on that terrible logic, he still should have had the opportunity to call the attorney who, in theory, may have been available without delay. The dissenting opinion looked like it was written by an actual jurist who wasn't just transparently going through the motions to reach a pre-determined conclusion. Looks like most of the 5 who concurred and the fella who penned the dissent were all Cuomo appointees for whatever that's worth.

Thanks for your beyond belief blogs stuff. looking for a Accountant In St Neots ? Check out this!