In 2021, Qualified Immunity Reform Died a Slow, Painful Death

Despite bipartisan momentum at the federal level, Congress still couldn't get anything over the finish line.

The year 2021 was widely seen, almost certainly foolishly, as the end of a dark era and the beginning of a much, much brighter one. It wasn't just the close of any year. It was the end of 2020.

Tied up in that was the supposed promise of criminal justice reform, coming off of a summer that saw qualified immunity transform from a lofty legal doctrine known by few to something seen on protest signs at rallies attended by thousands. And over the last 12 months, politicians took some steps to advance criminal justice reform. But as is the case with so many New Year's expectations, quite a bit also stayed exactly the same.

That stagnation came despite considerable bipartisan momentum propelling Republicans and Democrats toward reform in 2021, after the police killings of Breonna Taylor and George Floyd fueled a national conversation around accountability for law enforcement.

Central to that debate was qualified immunity, the principle conjured to life by the Supreme Court which allows various government officials to violate your rights without fear of a civil suit if the way in which they do so has not yet been "clearly established" in a prior court precedent. It's why, for example, two officers were able to allegedly steal $225,000 while executing a search warrant without having to explain that to a jury in civil court. We should all know stealing is wrong, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 9th Circuit noted, but without a court ruling that expressly applies to the particular circumstances in question, can we really expect government agents to apply that moral tenet?

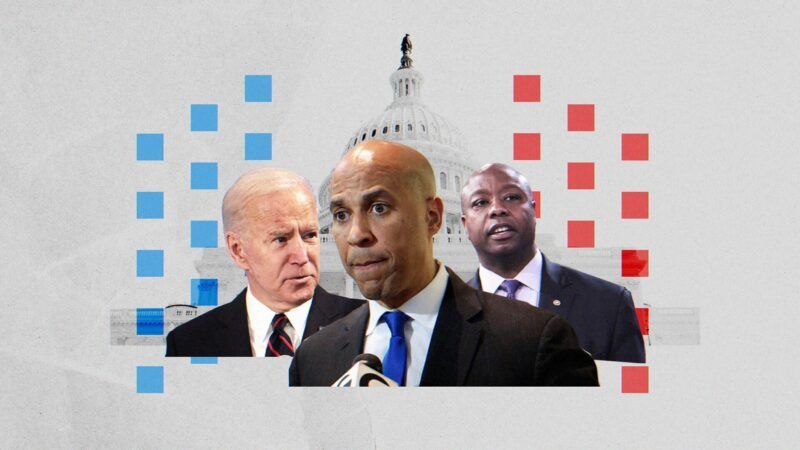

Many would say yes. That's why Sens. Cory Booker (D–N.J.) and Tim Scott (R–S.C.), flanked by Rep. Karen Bass (D–Calif.), appeared optimistic throughout the year that they would pass some version of the George Floyd Justice in Policing Act with limitations on qualified immunity. At the federal level, the proposal would have also banned chokeholds, carotid holds, and no-knock warrants for drug investigations, and it would have incentivized the same at the state level by tying those measures to federal funding. Further, it would have created a national database to track police misconduct—local departments are typically very opaque with such data—and it would have constrained the amount of military equipment passed down to departments across the country, among other provisions.

But the qualified immunity portion would prove to be the most difficult bridge to build, as the May 25, 2021, deadline to pass the Justice in Policing Act—imposed by President Joe Biden—came and went. Scott, who led Republican negotiations for the Senate, originally proposed a compromise where victims of police abuse would be able to sue departments instead of individual police officers. Some Democrats pushed back, questioning if it would provide any meaningful avenue to accountability. But it was reportedly Scott who distanced himself from his own provision after floating it with members of the law enforcement lobby.

Following months of negotiations, the deal—in its entirety—was pronounced dead in September.

"We started out the year thinking about George Floyd," says Cynthia Roseberry, deputy director of the Justice Division at the American Civil Liberties Union. "And then policing reform just went away. Qualified immunity remains even today."

It will likely remain for some time. There are other pieces of stalled legislation on various facets of criminal legal reform, Roseberry notes, that could have also become law, had Congress found the political will to do so this year. Those include the EQUAL Act, which would give relief to inmates who were sentenced to harsher prison terms for using crack instead of powder cocaine; the MORE Act, which would end federal marijuana prohibition; and the First Step Implementation Act, which would retroactively apply sentencing reforms to prisoners who were sentenced before the First Step Act of 2018 was passed into law.

Even still, there were some criminal justice reform successes that flew under the radar, says Kevin Ring, president of Families Against Mandatory Minimums. "California repealed its drug mandatory minimums, Maryland got rid of juvenile life without parole….There were still places where you could see progress and reforms move forward." He also mentions that, while the EQUAL Act is yet to pass the Senate, it passed the House of Representatives with 361 votes, even from conservative hardliners Jim Jordan (R–Ohio) and Kevin McCarthy (R–Calif.).

Though Congress holds the majority of the bargaining chips, Roseberry says she would like to see at least one thing from Biden: "He needs to use clemency now and often," she tells Reason. "If the sentence is wrong, if it's inappropriate at Christmastime or at the end of his term, it was inappropriate at the beginning of his term or during the rest of the year."

Presidents are indeed known to invoke their clemency powers as they're heading out of the Oval Office for the last time. A related decision recently came at the eleventh hour: The Department of Justice released a memo last week announcing that thousands of prisoners released on home confinement during the COVID-19 pandemic will be able to complete their sentences from home. "This was a do-no-harm measure," says Ring. "These people were already sent home….This was consolidating something that had already happened."

That doesn't mean those 2,800 prisoners are now free. They'll still be kept to a rigorous monitoring program, and any slip-ups can result in a one-way ticket to a cell. Such was the case with Gwen Levi, a 76-year-old woman who served 16 years for dealing heroin and was taken back to federal prison because she attended a word-processing class. So, too, did Jeffrey Martinovich meet that fate after failing to answer his phone during one of his nightly check-ins, although his GPS monitor showed he was at his house as required.

Of the thousands of inmates impacted by the recent decision, Ring adds that "it's clear these people shouldn't go back….I just want to make sure we find a way to avoid them getting violated over stupid little infractions…because the consequences are so great for these people. It's not like they'd go back for two months. They'd go back for five years."

Levi will get to reap the benefits of the Justice Department's memo; she was released again in July after a national outrage. Meanwhile, Martinovich, who was convicted of white-collar crimes in 2013, will call the Federal Correctional Institution at Beckley his home until August 25, 2025.

Despite some policy wins in 2021, victims of government misconduct will have to wait longer still for accountability reform. Rules and regulations for state actors may change, but that matters little if they cannot be held accountable for breaking those very guidelines. As never before, public opinion took a hard turn against qualified immunity—a doctrine that sends a message to government agents that they are above the laws they enforce. If the energy going into 2021 wasn't enough to move Congress, what will be?

Show Comments (43)