A Judge Has Ordered Him Released From Prison—Twice. The Government Still Won't Set Him Free.

Bobby Sneed's story highlights how far some government agents will go to keep people locked up, flouting the same legal standards they are charged with upholding.

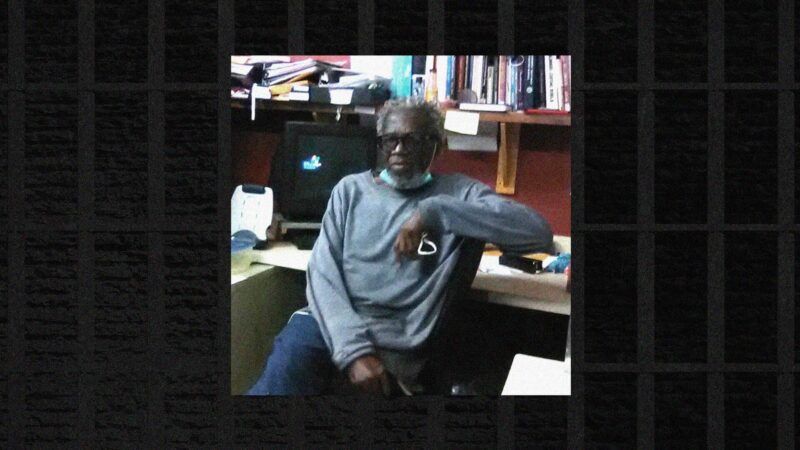

We don't know where Bobby Sneed will celebrate his 75th birthday this weekend, but two locations look increasingly likely: either the Louisiana State Penitentiary, also known as Angola, or a nearby jail. He has counted the majority of his milestones behind prison walls, having been incarcerated for more than 47 years for his role in a 1974 burglary.

This year was going to be different. The Louisiana Board of Pardons and Committee on Parole voted unanimously to release him months ago. Yet Sneed has remained in prison long past his March 29, 2021, release date and despite a November 18 court decision ordering his release.

Another ruling came down early last week: Sneed must be freed, a judge said. And as he was waiting by the gate for pickup, prison officials again refused to release him, instead rearresting him and transferring him to West Feliciana Parish Detention Center in St. Francisville, Louisiana.

It was an additional plot twist in Sneed's legal odyssey, set in motion by the Committee on Parole trying to undo its own decision and violating state law in the process. Sneed's story highlights how far some government agents will go to keep people locked up—flouting the same legal standards they are charged with upholding, even after they've publicly conceded the person poses no danger to society.

"The 'minimum requirements of due process' in the parole revocation context require 'disclosure of the evidence against him,' the 'right to confront and cross-examine adverse witnesses,' a 'neutral and detached' hearing body, and 'a written statement by the factfinders as to evidence relied on,'" wrote Judge Ron Johnson of the 19th Judicial District Court in East Baton Rouge Parish. "Because it is undisputed that no such procedures were followed when Mr. Sneed's parole was stripped…this Court finds that [he] was deprived…of due process of law."

In mid-March, not long after the Committee on Parole approved Sneed's release in a hearing that lasted 17 minutes, he collapsed in one of the prison dormitories. He was admitted to the infirmary, where he allegedly tested positive for amphetamine and methamphetamine. But there was no complete chain of custody on those urine samples, and thus no way to confirm to whom they actually belonged. And while the doctor's notes said that Sneed admitted to drug use, she later told Thomas Frampton, Sneed's attorney, that she wasn't sure why that was in her notes, because Sneed never told her that. He had been in and out of consciousness, unable to speak for himself.

Sneed maintained his innocence, and a disciplinary committee ruled in his favor. Yet that didn't stop the Committee on Parole from illegally moving to revoke his freedom during a brief May hearing, long after his release date had come and gone. At the time, he was supposed to be home with family. Instead, he sat in solitary confinement.

To avoid complying with the second court ruling ordering Sneed released, the Committee on Parole issued an arrest warrant Friday on another contraband charge.

This was the same panel that already acknowledged that Sneed no longer poses a risk to the community. (Sneed, a Vietnam veteran, suffered a stroke in 2005, after which point he had to relearn how to walk and talk.) But what if he is guilty of using contraband? Should that change their determination? "I don't believe that there's any threat to public safety….By keeping him incarcerated, at his age and with [his] medical conditions, it's more costly with very finite taxpayer dollars to keep him [locked up] than to help him get substance abuse treatment," says Kerry Myers, deputy director of the Louisiana Parole Project. "What's at stake is: What's the best use of resources?"

Prior to that May rescission hearing, Francis Abbott, executive director of the Louisiana Board of Pardons and Committee on Parole, told me that there was good reason to move forward as they did. "We've got documents that were submitted to the board that are not open to the public," he said. Sneed's legal team was also barred from seeing those documents. It was only after the hearing that the evidence—detailing, for instance, the doctor's comments on Sneed's alleged drug use—was provided to them. That paperwork allowed Frampton to track down the doctor who treated Bobby: the one who conceded that Sneed hadn't, in fact, admitted to anything. But Frampton wasn't able to counter the government's claims during the hearing, as he had not yet been provided with the basics.

That hearing, which I observed via Zoom, failed to incorporate basic legal standards, with the defendant unaware of the supposed evidence against him and with his team not allowed to call witnesses. "Indeed, Respondents' position was that they did not need to afford Mr. Sneed a proper revocation hearing," notes Judge Johnson in last week's decision.

His ruling came in response to Sneed's second federal civil rights lawsuit against Abbott and Tim Hooper, the warden at Angola. To circumvent the first suit, the government's motion-to-dismiss filing asserted that Sneed "failed to allege or show that Director Abbott possessed any actual statutory authority to take any official action with respect to [Sneed's] parole status or that he actually did so."

That argument and admission would circle back to haunt them once the public records were released. "Hold off on any paperwork," Abbott wrote to Whitney Troxclair, a parole administrator, on March 26 at 6:50 a.m., three days before Sneed's scheduled release. About an hour later, he then forwarded that email to Sheryl Ranatza, the Parole Board chair, apprising her of what he had done. "FYI Granted last Thursday and was scheduled to release Monday." In other words, the government seemingly admits that Abbott did not have the statutory authority to stop Sneed's release. And yet it appears that's what he did.

"Thanks for your continued interest in this matter, unfortunately we will not be commenting as this is an ongoing legal matter," Abbott told Reason last week.

In 1974, Sneed stood guard while three of his accomplices robbed a home and ultimately killed one of the residents who lived there. Though he was two blocks away when that murder occurred, he was charged with principal to commit second-degree murder—a conviction that was overturned after he successfully petitioned for the court to vacate it. The charge, which is similar to the felony murder rule, allowed the government to prosecute him for murder while also conceding he didn't kill anyone, on the grounds that it occurred during the commission of a related crime. He was re-convicted in 1987. "Mr. Sneed is deeply remorseful for his role in the murder of Mr. Jones," reads Sneed's suit. "His incarceration has given him time to reflect on his role in the offense and how he could have prevented the senseless act of violence that occurred." Out of the six defendants involved in that burglary, Sneed is the only one who remains in prison.

Following the prison's renewed refusal to set Sneed free, Frampton filed a motion to hold the state officials in contempt. So months after the government openly recognized that Sneed is no longer a hazard to the community, we'll soon find out if they'll succeed in clawing him back to prison for yet another birthday.

Show Comments (42)