SCOTUS Says State Judges and Court Clerks Can't Be Sued To Block Enforcement of the Texas Abortion Ban

The Court allowed claims against health care regulators to proceed, but that will not prevent the private civil actions authorized by the law.

The Supreme Court today held that Texas judges and court clerks cannot be sued to block enforcement of a state law that prohibits abortion after fetal cardiac activity can be detected. But it said the plaintiffs challenging S.B. 8, which took effect on September 1, can proceed with claims against state medical regulators.

Although S.B. 8 is clearly inconsistent with the Supreme Court's abortion precedents, Texas legislators sought to prevent early judicial review through a novel enforcement mechanism that relies on private civil actions. The law bars state or local officials from enforcing its terms, instead authorizing "any person" to sue "any person" who performs or facilitates a prohibited abortion, promising prevailing plaintiffs at least $10,000 in "statutory damages," plus reimbursement of their legal expenses.

The abortion providers who challenged S.B. 8 in Whole Woman's Health v. Jackson tried to get around that obstacle by suing Smith County District Court Judge Austin Reeve Jackson and District Court Clerk Penny Clarkston, representing a class of judicial-branch officials who they argued would play an essential role in enforcing S.B. 8 by docketing and hearing the lawsuits it authorizes. While U.S. District Judge Robert Pitman accepted that argument, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 5th Circuit deemed it "specious," saying the Supreme Court has made it clear that state judges are not proper defendants in cases challenging a law's constitutionality.

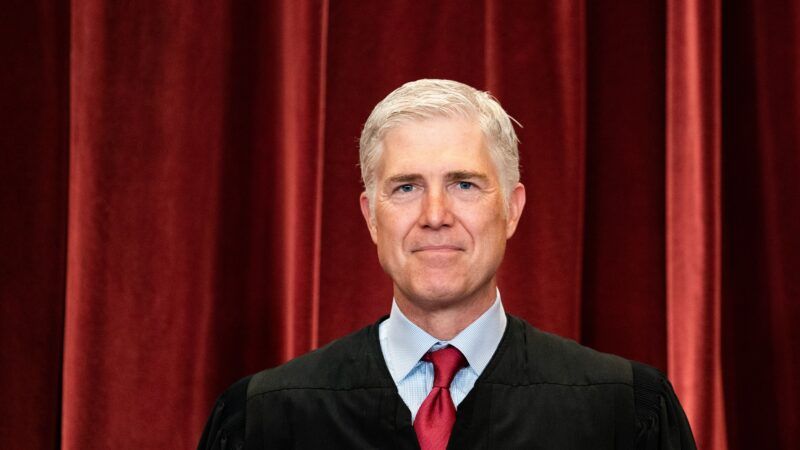

In today's decision, the Court agrees with the 5th Circuit on that point. "Generally, States are immune from suit under the terms of the Eleventh Amendment and the

doctrine of sovereign immunity," Justice Neil Gorsuch notes in his opinion for the Court. In the 1908 case Ex parte Young, the Court recognized an exception to that rule, saying state officials charged with enforcing an allegedly unconstitutional law can be sued in their official capacity.

"But as Ex parte Young explained," Gorsuch writes, "this traditional exception does not normally permit federal courts to issue injunctions against state-court judges or clerks. Usually, those individuals do not enforce state laws as executive officials might; instead, they work to resolve disputes between parties. If a state court errs in its rulings, too, the traditional remedy has been some form of appeal, including to this Court, not the entry of an ex ante injunction preventing the state court from hearing cases. As Ex parte Young put it, 'an injunction against a state court' or its 'machinery' 'would be a violation of the whole scheme of our Government.'"

Gorsuch also notes that "Article III of the Constitution affords federal courts the power to resolve only 'actual controversies arising between adverse litigants.'" While "private parties who seek to bring S. B. 8 suits in state court may be litigants adverse to the petitioners," he says, "the state-court clerks who docket those disputes and the state-court judges who decide them generally are not. Clerks serve to file cases as they arrive, not to participate as adversaries in those disputes. Judges exist to resolve controversies about a law's meaning or its conformance to the Federal and State Constitutions, not to wage battle as contestants in the parties' litigation."

The Court likewise ruled that Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton, who also was named in the lawsuit, is not an appropriate defendant. "While Ex parte Young authorizes federal courts to enjoin certain state officials from enforcing state laws," Gorsuch says, "the petitioners do not direct this Court to any enforcement authority the attorney general possesses in connection with S. B. 8 that a federal court might enjoin him from exercising."

By contrast, the Court says, the state health care regulators named as defendants seem to "fall within the scope of Ex parte Young's historic exception to state sovereign immunity," because "each of these individuals is an executive licensing official who may or must take enforcement actions against the petitioners if they violate the terms of Texas's Health and Safety Code, including S. B. 8." The Court says the abortion providers therefore can seek an injunction that would prohibit those officials from enforcing S.B. 8, although that would not bar civil actions by private plaintiffs.

The Court's conclusion regarding state judges was unanimous. So was its conclusion that the claims against Mark Dickson, a pro-life activist who supports S.B. 8 but says he currently has no plans to file any S.B. 8 lawsuits, should be dismissed. Most of the justices agreed that neither Paxton nor court clerks like Clarkston can be sued to block enforcement of S.B. 8. All of the justices except for Clarence Thomas agreed that the regulators are appropriate defendants.

Chief Justice John Roberts, in a partial dissent joined by Justices Stephen Breyer, Sonia Sotomayor, and Elena Kagan, notes that S.B. 8 "has had the effect of denying the exercise of what we have held is a right protected under the Federal Constitution." He reiterates his concern that "Texas has employed an array of stratagems designed to shield its unconstitutional law from judicial review." Those tricks, he says, "effectively chill the provision of abortions in Texas."

Roberts et al. would have allowed the plaintiffs to sue Paxton, since he "maintains authority coextensive with the Texas Medical Board to address violations of S. B. 8." They also think Clarkston is an appropriate defendant. "The mere threat of even unsuccessful suits brought under S. B. 8 chills constitutionally protected conduct, given the peculiar rules that the State has imposed," Roberts writes. "Under these circumstances, the court clerks who issue citations and docket S. B. 8 cases are unavoidably enlisted in the scheme to enforce S. B. 8's unconstitutional provisions, and thus are sufficiently 'connect[ed]' to such enforcement to be proper defendants."

In another partial dissent, Sotomayor, joined by Breyer and Kagan, notes that S.B. 8 "has threatened abortion care providers with the prospect of essentially unlimited suits for damages, brought anywhere in Texas by private bounty hunters, for taking any action to assist women in exercising their constitutional right to choose." She says "the chilling effect has been near total, depriving pregnant women in Texas of virtually all opportunity to seek abortion care within their home State after their sixth week of pregnancy." While people sued under S.B. 8 can raise constitutional arguments at that point, she writes, the law "skews state-court procedures and defenses to frustrate post-enforcement review."

In Sotomayor's view, "The Court should have put an end to this madness months ago, before S. B. 8 first went into effect." She warns that this "brazen challenge to our federal structure" may inspire imitation by legislators bent on undermining other constitutional rights recognized by the Court—a concern Justice Brett Kavanaugh raised during oral arguments in this case.

"This is no hypothetical," Sotomayor writes. "New permutations of S. B. 8 are

coming. In the months since this Court failed to enjoin the law, legislators in several States have discussed or introduced legislation that replicates its scheme to target locally disfavored rights." A footnote mentions proposals targeting gun rights as well as abortion rights.

"What are federal courts to do if, for example, a State effectively prohibits worship by a disfavored religious minority through crushing 'private' litigation burdens amplified by skewed court procedures, but does a better job than Texas of disclaiming all enforcement by state officials?" Sotomayor asks. "Perhaps nothing at all, says this Court. Although some path to relief not recognized today may yet exist, the Court has now foreclosed the most straightforward route under its precedents. I fear the Court, and the country, will come to regret that choice."

Show Comments (20)