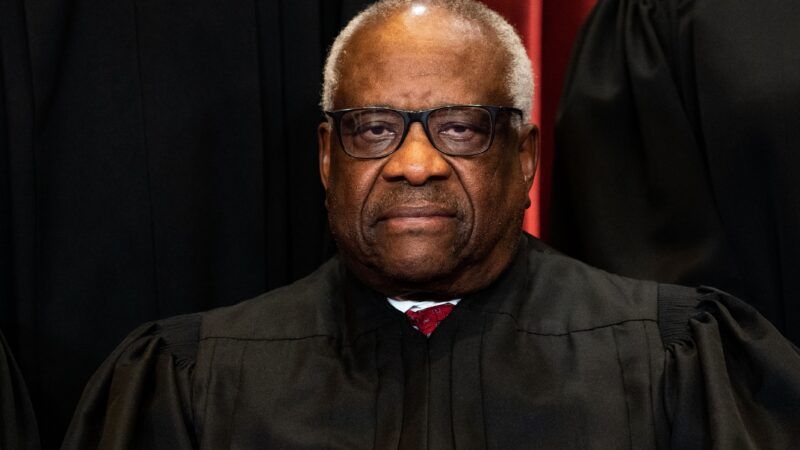

Clarence Thomas Blasts the 'Contradictory and Unstable' Federal Marijuana Ban

Sixteen years after Gonzales v. Raich, Thomas is back with another opinion criticizing the federal government’s marijuana ban.

In 2005, the U.S. Supreme Court heard arguments in a case pitting California's Compassionate Use Act, a voter initiative that legalized the use of medical marijuana within state borders, against the federal Controlled Substances Act, which outlawed the use of marijuana for any purpose anywhere in the nation. The question before SCOTUS in Gonzales v. Raich was whether the federal ban, which was based on the congressional power to "regulate commerce…among the several states," may be lawfully applied against medical marijuana that is cultivated and consumed entirely within just one state.

The feds won 6–3. The Controlled Substances Act "is a valid exercise of federal power," declared the majority opinion of Justice John Paul Stevens, who maintained that the Commerce Clause must be read capaciously so that Congress has the tools needed to reach such local activity as part of a "comprehensive" national regulatory scheme. Writing in dissent, Justice Clarence Thomas complained that "if Congress can regulate this under the Commerce Clause, then it can regulate anything—and the Federal Government is no longer one of limited and enumerated powers."

Sixteen years later, Thomas is back with another blast at the federal government's marijuana ban. What is more, Thomas now says that the federal government's own actions may have negated Raich's legal rationale. "Once comprehensive, the Federal Government's current approach is a half-in, half-out regime that simultaneously tolerates and forbids local use of marijuana," Thomas writes. "This contradictory and unstable state of affairs strains basic principles of federalism and conceals traps for the unwary."

Thomas' statement came in response to the Supreme Court declining to hear arguments in the case of Standing Akimbo v. United States. Standing Akimbo is a medical marijuana dispensary in Denver that operates legally under Colorado law. Yet, as Thomas points out, the company is still acting illegally under federal law, which means, among other things, that the company is at odds with the Internal Revenue Service over whether or not "their intrastate marijuana operations will be treated like any other enterprise that is legal under state law."

Thomas also describes other problems that similar enterprises still face thanks to the federal marijuana ban remaining on the books, even if the ban itself is rarely enforced:

Many marijuana-related businesses operate entirely in cash because federal law prohibits certain financial institutions from knowingly accepting deposits from or providing other bank services to businesses that violate federal law….Cash-based operations are understandably enticing to burglars and robbers. But, if marijuana-related businesses, in recognition of this, hire armed guards for protection, the owners and the guards might run afoul of a federal law that imposes harsh penalties for using a firearm in furtherance of a 'drug trafficking crime.'…A marijuana user similarly can find himself a federal felon if he just possesses a firearm.

"Suffice it to say," Thomas concludes, "the Federal Government's current approach to marijuana bears little resemblance to the watertight nationwide prohibition that a closely divided Court found necessary to justify the Government's blanket prohibition in Raich." In other words, if the feds are no longer regulating the marijuana market the way they said they were when Raich was decided, then the Raich decision may no longer be good law. "A prohibition on intrastate use or cultivation of marijuana," Thomas observes, "may no longer be necessary or proper to support the Federal Government's piecemeal approach."

Editor's Note: As of February 29, 2024, commenting privileges on reason.com posts are limited to Reason Plus subscribers. Past commenters are grandfathered in for a temporary period. Subscribe here to preserve your ability to comment. Your Reason Plus subscription also gives you an ad-free version of reason.com, along with full access to the digital edition and archives of Reason magazine. We request that comments be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment and ban commenters for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

This is why we will work tirelessly to have Thomas removed from the bench. There is no greater threat to the fabric of our democracy.

You've gone full OBL, I see.

USA Making money online more than 15000$ just by doing simple work from home. I have received $18376 last month. Its an easy and simple job to do and its earnings are much better than regular FFF office job and even a little child can do this and earns money. Everybody must try this job by just use the info

on this page.....VISIT HERE

For Online Jobs ... Visit Here

...what? How is opposing Federal marijuana restrictions anti-democratic?

It's a good thing you worked tirelessly to elect a former federal prosecutor who cackled about how she railroaded marijuana users despite confessing to smoking weed in her dorm while listening to Tupac and Snoop Dogg's albums a decade before they were recorded.

Charles Koch is up $6.63 billion this year. You're not going to convince any of his Reason.com employees to reconsider their Biden votes with this "Harris is arguably a marijuana hypocrite" approach.

#InDefenseOfBillionaires

Yet another racist Republican persecuting black youths with the war on drugs. Thank Martin Luther King Jr that we now have an 80 year old senile white Democrat and a BIPOC former federal prosecutor and drug warrior running the show to put an end to this injustice.

I thought MLK was cancelled a couple of years ago. For Me Too or, I dunno, something or other. I get confused.

BiPOC, to... that's new and a bit confounding. I don't know preciely what it's supposed to mean, but I'm guessing here and I think I got it. Though I'm still not sure why being bisexual people of color or whatever the F that means matters, but I'm pretty sure MLK is supposed to stay cancelled by the modern left as the content of your character is no longer important, the color of your skin is.

Well, unless your Clarence Thomas. I guess.

Damn, man, this whole ranking people thing is confusing.

I keep thinking it's bipolar coloreds.

As a black person with bipolar disorder I resemble that remark.

Dude, y'all are so unwoke.

It's Black, Indigenous, Purple, Orange, Cows.

Sheesh.

I had to login for that, perlhaqr, I bow. Thank you.

No bowing. Cultural appropriation.

MLK hasn't been cancelled, yet. But I hear he was asked to cancel himself, possibly by agents of the FBI.

""This contradictory and unstable state of affairs strains basic principles of federalism and conceals traps for the unwary."" No way. We've been assured that Top Men are, have been, and always will be in charge.

But which ones? Aye, there's the rub.

Former Reason boardmember Petr Beckmann observed that the Court is "no more than a child of its time." He explained that the Court "does not dispense justice: it dispenses beautiful words in which to clothe the prejudices of its time." Expect Long Dong to lay off of girl-bullying and focus on having cops shoot fewer people liable to shoot back at superstitious cops, politicians and judges. Goading Colombians to shoot their judges is very different from goading Americans into retaliating closer to home.

"if Congress can regulate this under the Commerce Clause, then it can regulate anything—and the Federal Government is no longer one of limited and enumerated powers."

You new here?

I imagine some of his colleagues kicked his shins under the table for saying the quiet part out loud.

Yeah but it made for good lawyer bidness a while back lots of signs in states near CO and WA. Nowadays it doesn't much matter but the feds will hang onto a law just in case they can use it someday.

He just wants to send a bag of his homegrown to Anita Hill, to show there's no hard feelings.

"Hard feelings;" not quite "Long Dong" but may still be a poor choicer of words.

Probably the best overall Supreme Court justice in the last couple of generations.

The scumbags like Ted Kennedy must have suspected that might be the case, thus their despicable, lowlife effort to destroy him. Thank goodness they failed!

His deference to the cops is troubling. None of them are "good" in the strictest sense of the word. Thomas's fealty is to the govt. and he is compromised because of it.

Roger that, thank you.

Above in reply to Weigel.

Clarence Thomas and Brett Favre... The two greatest men in my lifetime.

The controlled substances act is unconstitutional as there is no federal power to ban products or services. They can regulate in interstate commerce and thats it. Regulation does not mean ban.

Another example of "conservative" and "liberal" labels not making sense for judges. Reductive, inaccurate, vague.

There are significantly more 9-0 decisions than party-line votes. I don't know why people still buy into the myth of partisanship in the Supreme Court. Their decisions are driven by their legal philosophies, not their political ones, the most recent and visible example of which was the Gorsuch pro-transgender ruling.

There is sometimes correlation, but there is little to no political causation.

Too bad his wife would rather give Charlie Kirk handouts than use her last name to legalize weed. And Clarence clearly prefers upholding the rights of the police to the rights of the potheads.

Unfortunately, the SCOTUS declined to consider the lawsuit filed by the CO RX cannabis company challenging the disastrous and nonsensical federal marijuana ban (that has enriched and emboldened violent drug cartels for the past 75 years).

Alcohol prohibition was bought by the Glucose Trust, abetted by progressive, communist, prohibitionist eugenics pseudoscience. By 1927, over 95% of all alcohol in These States was made from glucose corn sugar. Once distillers again got the upper hand they paid politicians to ban hemp (which competed with beer) and LSD (an effective treatment for alcoholics). RICO laws further entrenched organized cartels and today cops are shooting citizens (and getting shot) and addiction to Chicom export narcotics is greatly increased.

here everything u wanna know about