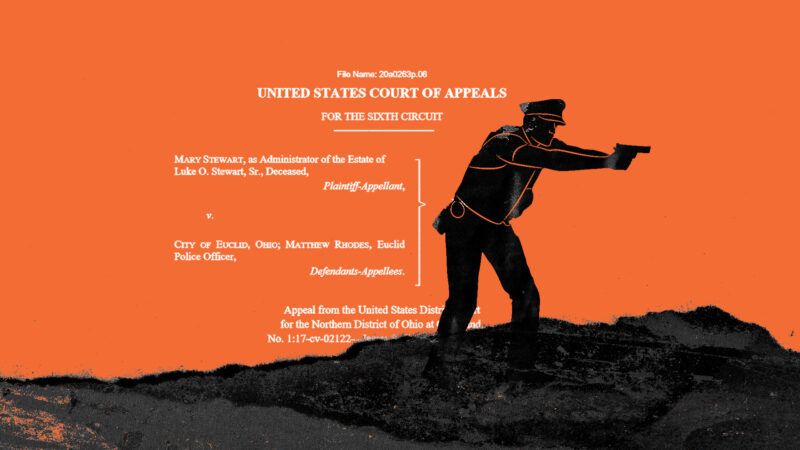

A Euclid Cop Killed a Man Who Had Been Sleeping in His Car. The Cop Can't Be Sued. The City Can't Be, Either.

The Supreme Court has a chance to fix this. The stakes are high.

On March 13, 2017, Luke Stewart was asleep in his car in Euclid, Ohio, when a man knocked on the window at 7 a.m. That man was Euclid Police Department (EPD) Officer Louis Catalani, though he did not announce himself as law enforcement. Startled, Stewart waved before starting the car and attempting to drive away.

Catalani and EPD Officer Matthew Rhodes weren't having it. The former opened the driver's side door, reaching his right arm around Stewart's face as he tried to dig into a pressure point underneath his jaw. Stewart began to scream. The latter entered via the passenger side and sought to eject Stewart from the vehicle. Neither effort worked, and Stewart drove off with Rhodes in tow.

That interaction lasted between 10–15 seconds. What happened next was similarly short-lived—59 seconds—and consisted of Stewart driving between 20–30 miles an hour while Rhodes punched him repeatedly, tased him six times, and hit him in the head with the taser, leaving an open wound. The minute concluded with Rhodes shooting Stewart twice in the torso, once in the neck, once in the chest, and once in the wrist.

He later died. He was 23 years old.

A federal court last summer agreed that a reasonable jury could find that Rhodes violated Stewart's constitutional rights when the officer shot him dead—a confrontation set in motion because Stewart had fallen asleep in his parked car. He was never told he was under arrest, nor did Rhodes ever display his badge. Yet in the same breath, the court said that Stewart's estate may not bring their lawsuit before any such jury, because Rhodes was awarded qualified immunity.

The legal doctrine prohibits victims from suing government officials for violating their rights unless the precise manner in which those rights were violated has been spelled out as unconstitutional in a prior court ruling.

Though it sounds farcical, that's not at all a surprising outcome. Yet there is a shocking part of the decision, handed down in August by the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 6th Circuit: They also shielded the municipality from the lawsuit on the grounds that the officer was protected by qualified immunity—something the U.S. Supreme Court specifically ruled against in Owen v. City of Independence (1980). That overreach will have major implications for how victims are able to hold cities accountable in the future.

In their suit, the Stewart estate zeroes in on the city's training program, alleging it left officers ill-prepared for the very serious duties they would undertake in the field. It appears it was not a very serious training program, weaving in jokes about use of force—it included a graphic, for instance, of a cop beating an unarmed suspect facedown on the ground with the caption "protecting and serving the poop out of you"—as well as Chris Rock's comedy routine on cops who assault suspects based on racial animus. "Get a white friend," he advises.

The 6th Circuit conceded such materials are "inappropriate," "tasteless," and "perhaps inadequate." Even so, the family will have no right to sue Euclid, they concluded, because Rhodes' misconduct was not "clearly established" in a prior court ruling.

"It is black letter law that municipalities are not entitled to qualified immunity," says Easha Anand, an attorney with the MacArthur Justice Center and lead counsel on the case. "The Supreme Court decided decades ago that the policy reasons we justify qualified immunity for individual officers…just don't apply to municipalities. The city of Euclid wasn't deciding in the heat of the moment whether to shoot or not shoot a potentially dangerous suspect. The city of Euclid has the luxury of time and space to design this really appalling PowerPoint."

The Supreme Court will again have a chance to weigh in on the matter, with Stewart v. City of Euclid on the docket for their consideration—a decision that will be released come Monday.

The stakes are high, perhaps stratospherically so, as Congress debates qualified immunity, one of the sticking points in negotiations over police reform. Sen. Tim Scott (R–S.C.), who is leading the GOP's side in the talks, recently floated what seemed like a major compromise, reportedly proposing that cities be held liable for claims instead of individual police officers. It remains unclear how such a plan would work if federal courts now assert that municipalities are effectively protected by qualified immunity.

"If this 6th Circuit decision is allowed to stand, and if qualified immunity is essentially extended into the area of municipal liability, then any kind of amendment that you make to ensure that municipalities are held accountable would have to account for qualified immunity," says Anya Bidwell, an attorney at the Institute for Justice. "It would make it even more complicated for Congress to amend municipal liability, because municipal liability would have this residual qualified immunity aspect."

Qualified immunity has protected two cops who assaulted and arrested a man for standing outside of his own house, two cops who allegedly stole $225,000 while executing a search warrant, and a cop who caused thousands of dollars in damage to a man's car during a bogus, hours-long drug search for which the officer did not lawfully obtain consent. Without analogous court precedents expressly outlining that misbehavior, the victims were barred from suing. There are many more such stories.

The standard required is incredibly myopic. "Stewart has pointed to no cases in this circuit involving an officer being driven in a suspect's car, much less a case that shares similar characteristics," such as the "speed" behind the wheel or the exact level of "aggression" Stewart exhibited, wrote Circuit Judge Eugene Edward Siler Jr. The kicker: Siler acknowledged that Stewart exhibited a "lack of aggression" toward Rhodes, and it is undisputed that the victim didn't exceed 30 miles per hour as he drove. Even though one might assume those factors would weigh in Stewart's favor, they don't. It doesn't matter that they look good for the victim; what matters is that no court precedent exists with that exact same fact pattern.

Such a denouement is all too common. That it now precludes holding the city accountable is not common, and it shouldn't become so. "The family has suffered an unimaginable loss," says Anand. "They've suffered that loss not because of a tragic and unforeseeable set of circumstances, but because of the kind of police interaction that officers should be trained to manage with the appropriate care and respect for civilian life." Even the 6th Circuit admitted that a jury could come to the same conclusion. As it stands, however, the Stewart family will have no right to appear before one.

Show Comments (79)