Coming Out of the Chemical Closet

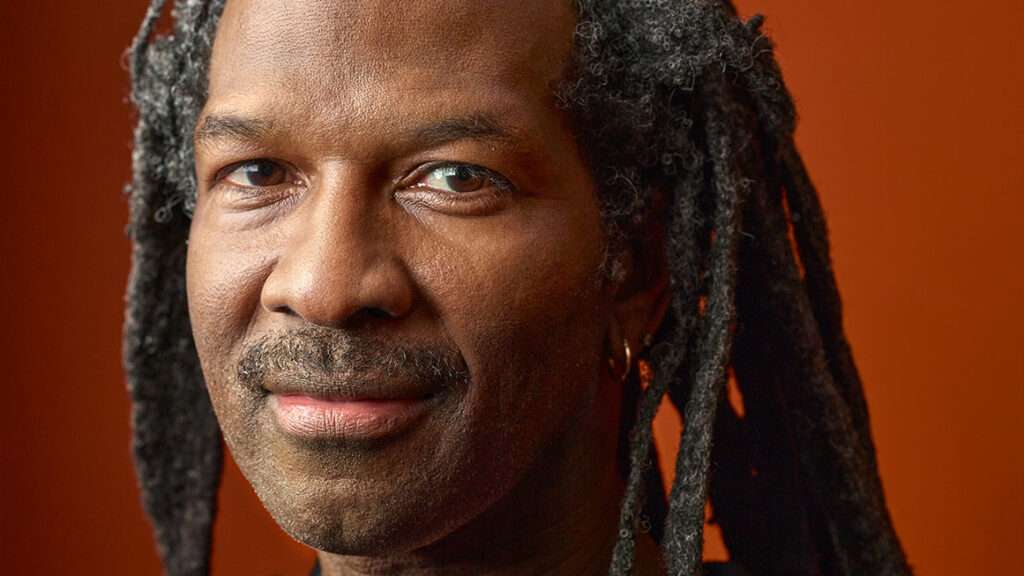

Neuropsychopharmacologist Carl Hart says most of what the public knows about drugs is both scary and wrong.

Carl Hart is a professor of neuroscience and psychology at Columbia University. He served in the United States Air Force, earned a Ph.D., and raised three children to adulthood. As he writes in his new book: "Each day, I meet my parental, personal, and professional responsibilities. I pay my taxes, serve as a volunteer in my community…and contribute to the global community as an informed and engaged citizen."

So it may surprise some people to learn that not only has Hart been responsibly using heroin regularly for more than five years but he's willing to tell people about it. He says his experiences with heroin make him a more forgiving and empathetic person, partner, and father.

Hart's path to drug use started in Miami in the 1980s—not by taking drugs but by trying to get people off them. When the media blamed crack for unemployment and murder in the community where he grew up, Hart decided to study neurobiology to develop medications to help people with drug addictions. Now he realizes that was naive: The crisis wasn't really about crack.

In his new book, Drug Use for Grown-Ups: Chasing Liberty in the Land of Fear (Penguin Press), Hart writes about being one of the millions of Americans who use drugs regularly and lead normal lives. "The vast majority of them are middle-class, responsible folks" who are in the chemical closet, he says. Hart hopes to reach these people and those who already know and love them. Perhaps politicians will eventually come along for the trip. But for now, Hart says, President Joe Biden "doesn't know this issue, doesn't care about this issue."

In January, Reason's Nick Gillespie spoke with Hart via Zoom about the science of drug use and how the media flub their coverage of addiction and overdose deaths.

Reason: Give me the elevator pitch of your new book.

Hart: Well, the elevator pitch is found in the subtitle: Chasing Liberty in the Land of Fear. What I'm trying to do is ask Americans to think about their own liberty, and not in this jingoistic false patriotic sense, but in terms of what the Declaration of Independence guaranteed: life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness for all of us, as long as we don't disrupt anybody else's ability to do the same. That means we get to live our life as we see fit. Taking drugs can be a part of that. It is a part of that for a lot of Americans.

I'm trying to show people that our promise, of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness, is inconsistent with our practice, this banning of drugs—drugs that people use in their pursuit of happiness as an expression of their liberty.

You point out in the book that we're using drugs all the time, whether it's caffeine, alcohol, or tobacco. Then we have what the government calls illicit drugs. Are there any drugs that you would say are bad that should be banned?

There are some drugs which we try to identify that are toxic. There was a drug called MPTP that we banned in the 1980s because we found out that it destroyed specific brain cells. That's good to ban those kinds of drugs that no one's seeking for their effects. Even when people accidentally made MPTP, they were seeking heroin. If heroin was available, nobody would be interested in MPTP. So sure, there are drugs that we learned are so toxic that we have to ban them. But certainly drugs like cocaine, heroin, MDMA [a.k.a. ecstasy], none of those drugs are anywhere near that category.

As you were writing the book, you were in your fifth year of using heroin. That just blows people's minds, the idea that you could be a heroin user and something other than a homeless person. But define "drug use for grown-ups." What is a grown-up?

I lay out in the prologue that this book is for grown-ups: people who are responsible, they handle their responsibilities, they are members of their community. This book is not for people who are immature, who are not handling their responsibilities. If they are not handling their responsibilities before drug use, they will be irresponsible after drug use. But what will happen is that people will blame drugs, when in fact drugs had nothing to do with it. You just have an irresponsible person.

You write early on that "it has taken me more than two decades to come out of the closet about my personal drug use." A question for you: What took so long?

Frankly, what took so long is that I was a coward. I was afraid of the blowback that would occur if I said, "Oh yeah, of course I do a little cocaine, MDMA, heroin." Having traveled around the world for this book—I went to multiple countries and five continents—one of the things that was clear is that there are millions of people using these drugs, but they're in the closet. Not only that, the vast majority of them are middle-class, responsible folks. We have this caricatured image of the drug user as being some irresponsible degenerate, which is not the case for most drug users.

Let's talk about heroin. You come out of the chemical closet not simply as somebody who smokes weed but as a regular heroin user. Heroin conjures up all kinds of alarms for people. They think that if you even talk about heroin too much, you will become addicted to it. Media reports always say it's like having 10,000 orgasms and you'll never want to do anything else. So talk about your use of heroin. Isn't this a dangerous, dangerous substance?

When I talk about my drug use, whether it's heroin, MDMA, or cocaine, I have to be careful. Because for so long in this country, we have been accustomed to talking about drugs like we were adolescents. We make jokes and so forth. I want to be clear that my heroin use is just like taking time out to go to a club, to see a comedian perform, or to go see a concert. I set aside that time for that activity, and I enjoy that activity in that moment. And when that moment is over, I'm done. I have to go back and do whatever other responsibilities I have. That's how I want people to understand my heroin use.

People say, "Why do you use heroin?" Why do people do alcohol? To unwind, to relax. The same is true with my heroin use.

I use heroin in part because it's really good at helping me to be more forgiving of other people—to look at my own behavior and see where I need to modify in order to be a better person. I have to constantly evaluate the impact of my behavior on that of other people, especially people who are subordinate. I don't want to ever be the source of their anxiety, such that it impacts negatively on their loved ones. I think about all of these things during those times when I use heroin. And so hopefully it helps to make me a better person, because I can forget about some of the petty things that I may have had in my mind. Instead, I learn how to be more forgiving and more magnanimous.

Let's push this a little bit. You have kids. You have a partner. Does it help with those relationships?

Absolutely. Oftentimes, my drug use is with my partner, and so we have discussions about our kids. Our youngest kid is 20, but we're just like any other parents. We can be pains in the asses to our children. So how can we be better parents? How can we support them in a more loving way, in a way that is more effective, in a way that is more acceptable, in a way that they find more helpful? All of these things. I think about my parenting and I think about my role as a partner when I'm using.

Have you done drugs with your kids?

No, no, no, no. I haven't done that.

You don't want to ruin it for them—because, I mean, would anything be worse than doing drugs with your parents?

It might be, but I'm not going to assume that my kids want to do drugs with me. I recognize that I'm 54. My kids are in their 20s and 30s, and I may be unhip to them. What is considered hip today is not their father, and that's their thing. I give them their space and they give me mine.

How do you take heroin? And where do you get it? I don't want you to out your dealer. But how do you get it and how do you consume it?

People oftentimes make this mistake in interviews—they say, "Oh, you shoot heroin?" Because we have connected heroin use with intravenous use only. And not that there's anything wrong with intravenous use, but I've never shot a drug. I understand that many people are seeking to get the immediate, rapid effect by putting a drug in their bloodstream. That's fine. I do heroin intranasally. There are blood vessels that go to the brain, so it gets there fast enough for me.

I like to have a drug intranasal or orally, because the onset of effects are slightly delayed, but they last longer. I like to pace myself, and I like to time it out so that I am psychoactively altered for a certain amount of time, the time that I like to be altered. But that's part of knowing pharmacology and being a fan of pharmacology.

We're in an age now where one of the phrases you hear almost every day is, "We need to follow the science." Part of what your book does spectacularly well is point out that even among scientists—and this includes a younger, anti-drug version of yourself—science oftentimes pushes the idea that "drugs are bad" and "a drug like heroin automatically leads to addiction." Where does that come from? Because science is supposed to be impartial. Scientists are supposed to check their biases at the door. Why does that not happen more in discussions of the effects of drugs, much less drug policy?

The first thing we have to recognize is that science and scientists are not the same. When we say science, we're talking about the data. Follow the data. Follow the evidence. Not the scientists. The scientists are just like Thomas Jefferson, just like me: We're all flawed and we have our own biases.

The scientists in terms of the war on drugs, their role is that they—and I include myself here—have made out like bandits. As long as we are exaggerating the harmful effects of drugs, that means that there's more money for grants investigating the harmful effects of drugs. And so we are incentivized to put our hands on the scale in a way that exaggerates the harmful effects associated with drugs. You give somebody an incentive to behave a certain way, guess what? They're going to behave a certain way.

What do you do with the irresponsible drug users? We have people who drink and who drink problematically. I myself don't drink anymore because I'm a bad drinker. How do you deal with that 10 percent to 30 percent of people who develop substance abuse issues with a given substance?

In the same way we deal with people who develop problems with alcohol. Actually, I hope we would do a better job. Our treatment in this country is horrible. I'm an expert in this area, and I don't know where I would send a loved one in this country for drug treatment. I'd probably send them to Switzerland.

It would be nice if we just simply treated the problem. That means that we have to look beyond the drug, because we know the majority of people who use that substance are not addicted. We know that for sure. You have to look at what's going on in that person's environment, what's going on with the person's biology. Is the person in pain? Physical pain? Emotional pain? Does the person have a co-occurring psychiatric illness? Has the person recently been rendered unemployed or underemployed? What's going on in a person's life?

We often don't do that. Instead, we focus on the drug, and we say, "Yeah, this is what heroin would do to you." That's not heroin. That's the economy doing that to people. But we never say that. We never blame G.M. for all the carnage that we see in some of these communities. It's much more appetizing to blame heroin.

Joe Biden is president. He is one of the architects of the drug war. When he was a senator, he pushed a lot of drug-prohibitionist legislation. He helped create the drug czar's office and things like that. He's also an architect of mass incarceration in the United States. Are you optimistic that he'll be a good president when it comes to questions about drug legality?

Am I optimistic about Joe Biden being good on drug policy and so forth? Not no, but hell no. Joe Biden, he doesn't know this issue, doesn't care about this issue. That's why my attention is focused on the people. This is a book written for the general population, and the general population will dictate what position the politician takes publicly. As you know, Vice President Kamala Harris advocated for legalizing cannabis nationwide. She didn't always have that opinion, but she's like any other smart politician. They understand the mood, and so she's going with the flow. My goal is to educate the public so that they will bring the politicians along with them. The politicians will follow the public on this.

Compared to 50 years ago, or even 20 years ago, people in America are now using more legal drugs. Everybody's medicine chest is filled with prescriptions that just weren't as widespread before. Do you think our cultural comfort level with taking licit substances has a positive effect in prompting people to think, "Maybe if a legal opioid helps me get through some pain, maybe the illegal cognate is not so bad"? What role do you think the expansion of pharmaceuticals in everyday life has had on the drug war and attitudes toward drugs?

I think it has helped with the education of people. People didn't realize that morphine and heroin are essentially the same drug. Now people understand this a little better.

Or Adderall and amphetamine, right?

Exactly. Adderall, the major ingredient is amphetamine. People understand this now a lot better. I think that's a good thing in terms of increasing public education around these substances.

One of the ways that we vilify a drug is by linking it to an out-group. It could be blacks and cocaine, Mexicans and marijuana, or youth culture and LSD in the 1960s. You had cases like the Diane Linkletter story, where she was supposedly taking LSD and jumped out a window (which turned out not to be the case). Or Len Bias, the University of Maryland basketball player who was drafted by the Boston Celtics and then died from a cocaine overdose. Could situations like these derail a rethinking of drug prohibition?

Those situations are going to happen. There are going to be people who get in trouble with substances. The real point is that we can't take that anecdote, that outlier, and let that influence what's going on with the larger public movement. The whole Len Bias thing—I still don't know what happened there. We give cocaine in our laboratory here at Columbia, thousands of doses a year, and never have seen these kinds of problems.

The problem is that we don't really demand a comprehensive autopsy or chemical analysis about what was in the person's system. We test for a certain number of drugs and that's it. We don't know about the adulterants. We don't know what was going on there. I've been trying to really investigate this. I get parents who send me their children's toxicology [reports] who have died from what was labeled a drug overdose. I look at the levels that they're talking about as inducing or causing this overdose, and they're nowhere near the levels that would be expected to produce an overdose—but there it is on the death certificate. I think there might be other compounds there that we don't know about, or something else is going on.

We read drug scare stories all the time. Somebody dies or some new drug of choice is announced in the press: It's methamphetamine, then it's heroin, then it's a prescription opioid, then it's marijuana, which is stronger than your father's marijuana, etc. What are the kinds of things that people who want to be critical readers of drug prohibitionist accounts should be looking for?

Whenever something says, "We have never seen anything like this. This is more addictive than anything we've seen," get ready to be told some bullshit. If you see some story about "one hit, you're addicted" or "a few hits, you're addicted," bullshit. Addiction by definition requires that the person put in work. That means multiple occasions. When people say that this person died from a drug overdose, the question you should ask is, "How many drugs were in the person's system and what were the levels?"

You've lived a patriot's life. You're speaking now in the name of liberty for all, and that is a recurring theme with you. You also served in the military. Why did you join the service?

I joined the service originally because I didn't get a basketball scholarship that I thought I would get. So I thought, "I'll go to the military, and I'll complete some college courses there, and that way I can get a degree without having to pay much money for it." But just like many Americans, I was brought up on those patriotic, jingoistic sort-of phrases. At the core, I want to be a proponent of liberty and justice for all. I really believe in it, because it's the only thing I really have to believe in.

The world is watching us. All of these countries look at our Declaration of Independence. I understand how fragile this democracy and any democracy is. I really understand it now. That's why I really hope that people reevaluate what the Declaration of Independence means. It's such a brilliant document. I wish we taught it at the college level more. It's wasted on those young people in school. It needs to be taught on Capitol Hill. I don't think they understand what it means.

A year from now, what do you hope Drug Use for Grown-Ups has accomplished?

I hope that it spurred a conversation in every American home, whether they agree or disagree. I hope it spurred some people to go and read about drugs who otherwise would not have. And once Americans actually read something, once they read this book, they will see, "Hold up. Something's very wrong. This [drug prohibition regime] is very inconsistent with what our idea of being an American is." So that's what I hope. I hope every American household is having this conversation.

This interview has been edited for clarity and style. For a podcast version, subscribe to The Reason Interview With Nick Gillespie.