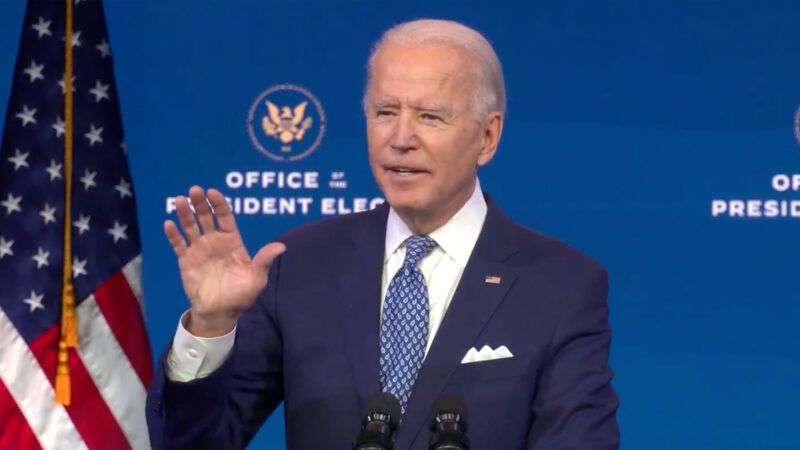

Biden Acknowledges Constitutional Limits to the Power of the Presidency

That’s a rare position for modern White House residents, and not necessarily a popular one with the public.

If you're looking for good political news to savor in an era that has little to offer, here's something: President-elect Joe Biden acknowledges that there are limits to the power of the presidency and its ability to unilaterally enact policy. That hasn't been a popular view among presidents in over a century, to the point that it's almost jarring to hear a soon-to-be holder of the office admit that he has no authority to make people jump on command.

There's no guarantee that Biden won't succumb, just like so many of his predecessors, to the temptation to stretch presidential power. But let's enjoy the moment while we can.

In a recording acquired by The Intercept of a Zoom meeting with civil rights figures held on December 8, attendees can be heard repeatedly calling on Biden to use the power of the presidency to achieve a host of goals, including police reform and investigations of potential threats to democracy. Biden got an earful about the things the prominent people with whom he was meeting wanted him to do through executive orders. (Audio excerpts can be heard at the December 10 edition of the Deconstructed podcast.)

He didn't encourage them with his response:

There's some things that I'm going to be able to do by executive order and I'm not going to hesitate to do it, but what I'm not going to do is … I am not going to violate the Constitution. Executive authority that my progressive friends talk about is way beyond the bounds.

Biden went on to add:

There is a Constitution. It's our only hope. Our only hope and the way to deal with it is, where I have executive authority, I will use it to undo every single damn thing this guy has done by executive authority. But I'm not going to exercise executive authority where it's a question, where I can come along and say, 'I can do away with assault weapons.' There's no executive authority to do away that. And no one has fought harder to get rid of assault weapons than me, me, but you can't do it by executive order.

Outgoing President Donald Trump has a very different take on executive authority. "When somebody is the President of the United States, the authority is total, and that's the way it's got to be," Trump told reporters at the White House last April.

"It's total? Your authority is total?" he was asked in disbelief.

"It's total," Trump answered. "It's total."

The current president is far from the first to think he's an elected monarch. The Clinton White House added a new phrase to the political lexicon with its enthusiasm for bypassing Congress to take unilateral action.

"With some of his closest advisers deeply pessimistic about the chances of getting major legislation passed during the rest of the year, Mr. Clinton plans to issue a series of executive orders to demonstrate that he can still be effective," The New York Times reported in 1998. "'Stroke of the pen,' Paul Begala, an aide to Mr. Clinton, said in summarizing the approach. 'Law of the land. Kind of cool.'"

Bill Clinton also didn't invent that view of the office. Whether explicitly or behind the scenes, the same attitude has prevailed among presidents at least since the era of Theodore Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson, who both rejected earlier conceptions of a restrained chief executive.

"The constitutional presidency, as the Framers conceived it, was designed to stand against the popular will as often as not, with the president wielding the veto power to restrain Congress when it transgressed its constitutional bounds," wrote Gene Healy in his 2008 book The Cult of the Presidency. "In contrast, the modern president considers himself the tribune of the people, promising transformative action and demanding the power to carry it out."

So, it's refreshing to hear Biden reject the idea that his authority is total and that he can accomplish anything he wants with a stroke of the pen.

But voicing ideals is one thing; sticking with them is entirely another. As the recording of Biden's meeting with civil rights leaders demonstrates, presidents are under a lot of pressure to act like kings, whatever they may think of their own legitimate authority. It takes a lot of backbone to stand against allies who helped you win office and who care more about results than about constitutional niceties.

"Today, we're far more open than our grandparents were to the idea that the president may be a crook or a clown; yet, we still expect the 'commander in chief' to heal the sick, save us from hurricanes, and provide balm for our itchy souls," Healy noted in his book.

Some progressives are taking Biden's comments not as encouraging evidence that he wants to rein-in the imperial presidency, but as a sign that more arm-twisting is in order.

"As this tape shows, as receptive as Biden might be to the arguments activists are making, he won't get there on his own," Paul Waldman wrote for The Washington Post. "They're going to have to keep pushing him."

That's the sort of take, from across the political spectrum, that has encouraged presidents of both major parties to expand the power of their office. The newly enriched presidency is then handed on to successors who do the same—logically resulting at some point in the future, it would appear, in an elected god-king with unlimited authority.

Maybe Joe Biden will be the first president in over a century to abide by constitutional limits on the power of the office and to resist calls to act like a monarch. That's asking a lot of a mere mortal—especially one who has spent decades pursuing the White House—but his initial instincts appear to be good.

Show Comments (149)