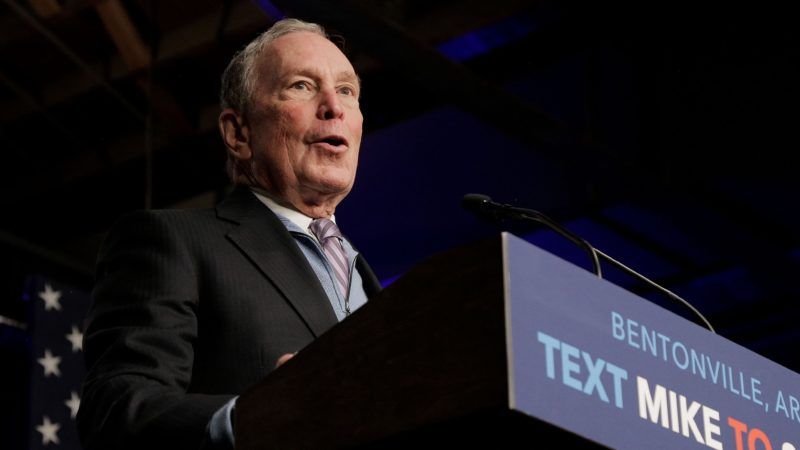

If Bloomberg's Arrogance Worries You, His Weaselly Positions on Presidential Power Won't Reassure You

The presidential candidate reserves the right to wage unauthorized wars, kill Americans in foreign countries, prosecute journalists, and selectively flout the law.

The ban on big beverages that Democratic presidential contender Michael Bloomberg tried to impose when he was mayor of New York City reflects not only his strong paternalistic instincts but also his impatience with legal restraints on executive power. Instead of seeking new legislation restricting sales of sugary drinks, Bloomberg unilaterally decreed, via the New York Board of Health, that customers of food service establishments would not be allowed to buy more than a pint at a time. A judge, an appeals court panel, and the state's highest court all agreed that the soda serving ceiling exceeded the board's legal authority.

Given Bloomberg's history of pursuing his goals without regard for the separation of powers, voters might reasonably wonder whether he would respect legal limits on his authority as president. A New York Times questionnaire about presidential power gave him an opportunity to reassure them. But for the most part, his weaselly responses can only reinforce fears that a President Bloomberg would do what he thinks is right, whether or not it is authorized by the Constitution.

Bloomberg thinks the president has the authority to wage war at his own discretion, whenever he believes it is "necessary to protect the country":

I would be extremely reluctant as President to commit the armed forces to hostilities in another country, without congressional authorization, beyond circumstances that involve an imminent threat to the United States, its people or property. It would be unwise for me as a candidate for president to categorically rule out committing the armed forces in such circumstances. I know that unforeseen circumstances can arise in matters of national security. But bypassing Congress should only be contemplated when action is necessary to protect the country and is limited in scope and duration.

Bloomberg also believes the president has the authority to assassinate U.S. citizens in foreign countries based on allegations that they are involved in terrorism. "I would have no hesitation to authorize lethal force against such an individual overseas in a location where arrest or capture is infeasible," he said, "so long as our national security lawyers determine such action is lawful."

As for terrorism suspects in the United States, Bloomberg said he "would be extremely concerned if a U.S. citizen were arrested on U.S. soil, by U.S. law enforcement, and turned over to the U.S. military for wartime detention and criminal prosecution in a military commission." He added that "our federal civilian courts have an impressive track record of bringing suspected terrorists to justice, both in terms of efficiency and security."

The Times asked Bloomberg about three cases in which the president violated the law in the name of national security: "After 9/11, the NSA wiretapped on domestic soil without court orders seemingly required by the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act, and the CIA used coercive interrogation techniques on prisoners despite antitorture laws and treaties. In the 2014 Bergdahl deal, the military transferred five Guantanamo detainees to Qatar without giving Congress the 30 days notice seemingly required by a detainee transfer law."

Bloomberg acknowledged the illegality of those actions and said he rejects Attorney General William Barr's broad view of presidential authority. But then he added this: "As president I would govern by the principle that presidential authority is at its zenith when authorized by both the Constitution and acts of Congress, and is at its weakest and riskiest when contrary to an act of Congress but somehow authorized by a broad reading of the Constitution."

That allusion to Youngston Sheet and Tube Co. v. Sawyer, the 1952 case in which the Supreme Court ruled that President Harry Truman's seizure of steel mills violated the separation of powers, is meant to be reassuring. But the formulation still leaves Bloomberg wiggle room to act "contrary to an act of Congress" if he believes Congress has impinged on the president's authority.

Bloomberg likewise hedged on the practice of replacing vetoes with signing statements that reserve the right to ignore specific provisions of a bill that the president finds objectionable. "If a bill is unconstitutional," he said, "the right response is almost always to veto it, not to sign it and to say that it is unconstitutional. But in very rare circumstances—which I hope would never arise—I would reserve the right to follow longstanding practice and sign a bill of which I generally approve, but also to point to Constitutional weaknesses in specific provisions."

The Times asked Bloomberg about the federal indictment of WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange, which includes Espionage Act charges that effectively criminalize the work of investigative journalists whose reporting is based on classified material. "Are these charges constitutional?" the paper asked. "Would your administration continue the Espionage Act part of the case against Assange?"

Instead of answering those questions, Bloomberg offered an anodyne statement about freedom of the press, followed by a promise that he "would adopt a very strong presumption" against trying to imprison reporters who share information the government would prefer to keep secret. You might expect a firmer commitment from a man who made his fortune in the news business.

On the positive side, Bloomberg said Congress has the power to criminalize corrupt uses of presidential power, and he agreed that the president can be guilty of obstructing justice when he uses his otherwise lawful authority to "impede an investigation for corrupt reasons," although he hedged on the question of whether a sitting president can be indicted. He also said executive privilege "should never shield criminal or improper communications" and "in general" should be limited to "deliberations or policy advice directed to the president from within the executive branch."

Answers to press questions about executive power obviously do not constitute a binding contract. Barack Obama, responding to a similar questionnaire in 2007, went considerably further than Bloomberg on the issue of the president's war powers, categorically stating that "the President does not have power under the Constitution to unilaterally authorize a military attack in a situation that does not involve stopping an actual or imminent threat to the nation." That did not stop Obama, once elected, from attacking Libya, Syria, and ISIS without congressional approval or an imminent threat to the nation.

Still, a candidate's understanding of presidential authority is unlikely to become more restrained after he moves into the White House. Bloomberg has put us on notice that, when it comes to waging war, killing Americans in foreign countries, selectively flouting the law, and prosecuting journalists, he will do whatever he thinks is appropriate. Voters have to decide whether they are comfortable with that prospect.

Show Comments (56)