Trump's Trade War Has Hurt American Manufacturers More Than It Helped Them

That should be fairly obvious to anyone who has been following the news, but a new report from the Federal Reserve provides the empirical evidence.

President Donald Trump's trade war has been a losing proposition for American manufacturers, which have suffered from higher prices and reduced market access.

That is exactly what many economists predicted would happen when the Trump administration slapped tariffs on steel, aluminum, and billions of dollars of Chinese imports in 2018. And it's exactly what news reports and economic data have suggested for months, as the manufacturing sector has struggled to keep up with other, stronger sectors of the American economy.

But a new report from two economists on the Federal Reserve Board goes beyond the theoretical implications of tariffs and the anecdotal evidence that the trade war has not worked.

"We find that U.S. manufacturing industries more exposed to tariff increases experience relative reductions in employment as a positive effect from import protection is offset by larger negative effects from rising input costs and retaliatory tariffs," write Aaron Flaaen, a senior economist with the Federal Reserve's Industrial Output Section, and Justin Pierce, a principal economist with the Industrial Output Section.

In short, protectionism doesn't work.

Flaaen and Pierce say their research provides "the first comprehensive estimates" of how the Trump administration's tariffs have affected American manufacturers by warping global supply chains and increasing the cost of input goods—which makes American goods less competitive in the global market. While tariffs have benefited American manufacturers by reducing some foreign competition, they write, those benefits have been overwhelmed by the costs, which have resulted in a reduction in manufacturing employment.

"For manufacturing employment, a small boost from the import protection effect of tariffs is more than offset by larger drags from the effects of rising input costs and retaliatory tariffs," the two economists conclude.

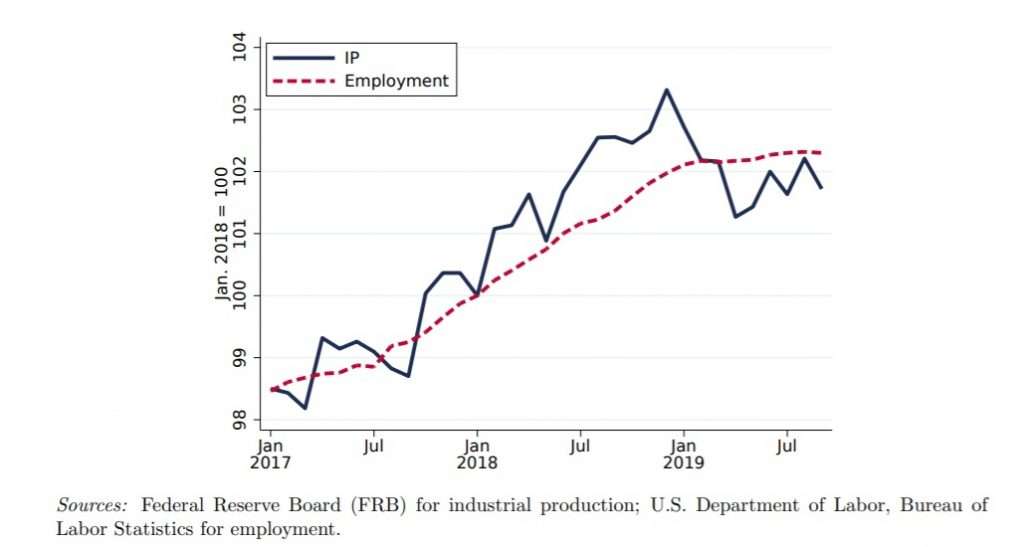

Indeed, the Federal Reserve's economic data shows a sharp decline in manufacturing output and a slowdown of job growth in the manufacturing sector—both beginning in mid-2018 as the tariffs were imposed.

The new report is an aggregate, comprehensive look at how tariffs have whacked American manufacturers, but it tracks with what many American companies have been saying and doing for months now. Thousands of domestic businesses have sought exemptions from the Trump administration's tariffs—effectively begging to be saved from the very policies Trump says are supposed to be helping them. The process for getting an exemption, as Reason has previously reported, is expensive, time-consuming, and lacks transparency and due process. Nevertheless, many businesses seem to have decided it is better to roll the dice on getting an exemption than to pay higher prices to import the manufacturing inputs they need.

Each time the Trump administration has sought to increase tariffs on Chinese imports, owners and executives of dozens of potentially affected businesses have made their way to Washington, D.C., to argue against the tariffs in byzantine hearings that have (mostly) been ignored by the administration and the general public.

Business owners aren't jumping through hoops to avoid tariffs because they have a faulty understanding of their own supply chains. They have a much better understanding of the consequences of the Trump administration's trade policies than the bureaucrats and ideologues imposing those tariffs.

The tariff-caused problems harming American manufacturers also mirror what's happened to other supposed beneficiaries of the Trump administration's trade policies. Tariffs on imported steel were supposed to boost domestic production, but this year has provided a steady stream of news reports about steel plants laying off workers, slowing production, and even suing the government to stop the tariffs. Meanwhile, the White House has quietly shifted its trade strategy to focus on China instead of Trump's promise to resurrect American steelmaking.

On the China front, Trump has tried to save face by recently striking a so-called "Phase One" trade deal that could result in tariff reductions next year and includes a promise that China will buy more American farm goods. If that means 2020 will be marked by the winding down of a destructive and unnecessary trade war, we should all be celebrating.

But one of the few benefits to come from the Trump administration's nearly two-year-long trade war is that economists got new, empirical evidence about why tariffs don't work—and why they fail especially in an economy that relies on global supply chains for both imports and exports.

"Our results suggest that the traditional use of trade policy as a tool for the protection and promotion of domestic manufacturing is complicated by the presence of globally interconnnected supply chains," Flaaen and Pierce write. "While the potential for both tit-for-tat retaliation on import protection and input-output effects on the domestic economy have long been recognized by trade economists, empirical evidence documenting these channels in the context of an advanced economy has been limited."

Trump's trade war hasn't done much for American manufacturers or workers. But at least it has proven, once again, that tariffs are bad policy.

Show Comments (269)