As the Dismissed Charges Against Paul Manafort Show, New York Democrats Love Double Jeopardy When It Hurts Trump's Cronies

Recent revisions to state law will facilitate such duplicative prosecutions of people associated with the president.

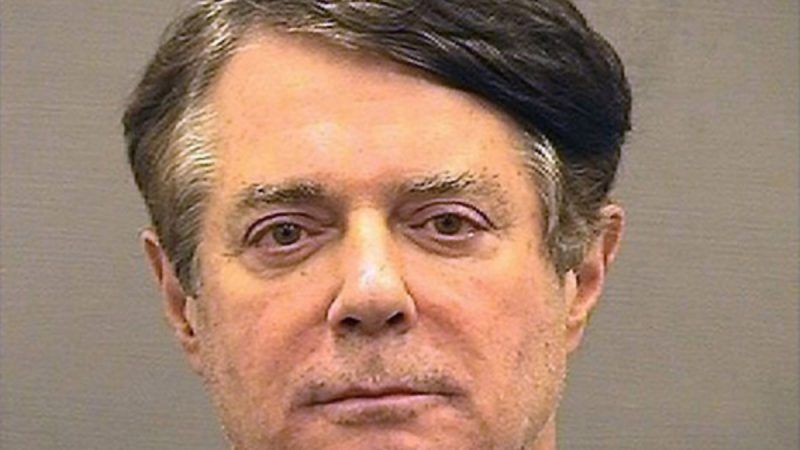

Yesterday, a New York judge dismissed state fraud charges against former Trump campaign chairman Paul Manafort, deeming them inconsistent with the state's double jeopardy law. Manafort, who turned 70 last April, is already serving a federal sentence of seven and a half years, based largely on the same conduct that underlies the state charges. Manhattan District Attorney Cyrus Vance sought to prosecute him again for those actions, lest presidential clemency reduce the punishment imposed on a Trump crony.

If you are thinking that's a blatantly political motive for a decision that is supposed to be based on considerations of justice, you are not wrong. Worse, New York's Democrat-controlled legislature amended the double jeopardy law last spring to facilitate such duplicative prosecutions in cases involving people associated with the president who benefit from clemency.

Last year a federal jury in Virginia convicted Manafort on two counts of bank fraud and deadlocked on seven other bank fraud counts, all related to misinformation in mortgage applications. (It also convicted him on five counts of filing false tax returns and one count of failing to report foreign bank accounts, but those charges are not relevant to the New York case.) Manafort later agreed to a plea deal in a separate federal case, brought in Washington, D.C., involving charges of witness tampering and conspiracy against the U.S. government. Under that agreement, which ultimately resulted in a 43-month prison sentence, Manafort admitted to the conduct underlying the hung bank fraud counts, which the Justice Department agreed to dismiss.

U.S. District Judge T.S. Ellis III, who oversaw the Virginia case, initially said he was dismissing those counts "without prejudice," even while expressing doubt that they could ever be reinstated. In the judgment he issued last March, he said he was dismissing the hung counts "with prejudice." He nevertheless took the underlying conduct into account when he sentenced Manafort to 47 months in prison.

A few days before Manafort received that sentence, a grand jury in Manhattan indicted him on 16 state fraud charges, based on the same inaccurate mortgage applications that had led to his federal prosecution in Virginia. The New York Times reported that the charges were "designed to thwart a Trump pardon."

According to the U.S. Supreme Court, this sort of redundant prosecution does not violate the Fifth Amendment's ban on double jeopardy. But New York has a statute that provides broader protection for defendants in situations like this. It says "a person may not be separately prosecuted for two offenses based upon the same act or criminal transaction."

The question for Maxwell Wiley, the New York judge who dismissed the state charges against Manafort, was whether that law barred Vance's attempt to "thwart a Trump pardon." The answer might seem obvious, since Vance's prosecutors "concede[d] that the charges in the relevant counts in the Federal Indictment, including those in the Hung Counts, were based on the same acts and transactions that form the basis of all the charges in this New York State indictment." But Vance argued that the state charges were authorized by two exceptions to the double jeopardy law.

One exception applies to proceedings that are "nullified by a court order which dismisses the accusatory instrument but authorizes the people to obtain a new accusatory instrument charging the same offense or an offense based upon the same conduct." Wiley concluded that Judge Ellis' dismissal of the hung bank fraud counts did not amount to such an order.

The statute also says a defendant may be "separately prosecuted for two offenses based upon the same act or criminal transaction" when "each of the offenses as defined contains an element which is not an element of the other, and the statutory provisions defining such offenses are designed to prevent very different kinds of harm or evil." While the state charges against Manafort do contain elements that were not elements of the federal offenses, Wiley ruled, it cannot be credibly maintained that the state and federal statutes defining those offenses are aimed at "very different kinds of harm or evil."

Both the federal bank fraud statute and the New York statute criminalizing residential mortgage fraud, Wiley said, were aimed at "preventing the type of financial fraud that led to the financial crisis of 2008." He concluded that the other state laws under which Manafort was charged, addressing conspiracy, falsification of business records, and schemes to defraud, likewise were aimed at problems similar to those addressed by the federal laws under which he already had been prosecuted.

The recent revisions to New York's double jeopardy statute, which Gov. Andrew Cuomo (D) signed into law on October 16, allow Vance and like-minded prosecutors to avoid all this complicated business. The amended law includes a new exception for former executive branch officials who served in positions requiring Senate confirmation, former members of the president's executive staff, and former employees of his campaign, transition team, businesses, or nonprofit organizations who benefit from presidential clemency after they are prosecuted for federal offenses. The exception also applies to people who are related to the president "by consanguinity or affinity within the sixth degree."

In case those broad categories don't do the trick, the exception extends to anyone who "bears accessory liability" for crimes committed by people associated with the president. There are also catchall categories for acts of clemency that help the president avoid "potential prosecution or conviction," that are related to crimes that benefited him, or that provide relief for a person who has information "material to the determination of any criminal or civil investigation, enforcement action or prosecution" involving the president.

Supporters of the bill that closed what they call "the Double Jeopardy loophole" argued that a president should not be able to suppress damaging information that might emerge from state prosecution of former underlings by pardoning them for federal offenses that are also criminal under New York law. "Either in the past or in a continuing manner, the president has talked about using the pardon power in a corrupt way to undermine the rule of law," said the bill's Senate sponsor, Todd Kaminsky, a Democrat who represents part of Long Island. "I think New York doesn't have to sit by and let the capricious use of the pardon power tie its hands."

But New York's Trump-inspired tolerance for double jeopardy sweeps more broadly than Kaminsky's high-minded rationale suggests. Why throw everyone connected to Trump under the bus, instead of simply allowing state prosecutions in cases where it can be shown that a pardon or commutation helped him avoid civil or criminal liability? The breadth of the new exception makes sense if it is a cudgel to beat Trump allies, less so if it is all about preventing him from "using the pardon power in a corrupt way to undermine the rule of law."

The revised law authorizes double jeopardy for anyone in Trump's orbit—including former secretaries, second cousins, and low-level campaign employees—who is convicted of a federal offense, even if the crime seems minor and the punishment disproportionate. Trump could still use his clemency power to help such a person, but that would not stop New York prosecutors from trying him again for the same conduct, assuming they can find a state law that applies.

If, say, Trump commuted the mandatory minimum sentence of a drug offender who once worked for one of his businesses, she would still be subject to state prosecution for the same crime. Meanwhile, a similarly situated defendant who committed the same offense but never made the mistake of working for Trump would not have to worry about a second prosecution. Call that distinction whatever you like, but it surely does not seem like upholding the rule of law.

Show Comments (18)