S.C. Judge Rules the Obvious: It's Unconstitutional for Police to Seize and Keep People's Property Without Proving They Committed Crimes

Law enforcement and prosecutors have seized millions from people they’ve arrested. That might be coming to an end.

Thanks to chronic abuse and misuse by local police departments, the days may be numbered for South Carolina's forfeiture system that allows cops to seize and keep cash and property of the people they arrest in order to fund their own departments.

Circuit Judge Steven H. John has ruled that the South Carolina's civil asset forfeiture regulations violate the Fifth, Eighth, and Fourteenth Amendment rights of the citizens.

Civil asset forfeiture has been in the crosshairs across the country for years now because it allows police and prosecutors to declare that any money or property owned by a suspect is "connected" to a crime, seize it, and then ultimately keep it for themselves. And because this is a civil process, police and prosecutors can do this without having to convict anybody. It's the assets that are considered the defendants (in this case, the respondent is actually the $20,771 that Horry County wants to seize from a man charged with trafficking cocaine), prosecutors typically have a lower threshold to make their case than "beyond a reasonable doubt," and people who are pulled into these forfeiture cases don't have access to public defenders and have to fund their own lawyers.

The end result: Police trying to keep whatever they can grab off anybody they arrest, claiming it's all proceeds or property connected to criminal activities, and using it to line their own pockets. This incentivizes police to look for people who have assets that can be seized. Local newspapers in South Carolina teamed up to investigate the extent of abuses and discovered police agencies across the state had seized more than $17 million in assets across three years. In one-fifth of the cases, nobody was charged or even arrested for a crime.

Judge John notes all of these problems in a decisive ruling that smacks down the practice of civil asset forfeiture. In his 15-page opinion, he writes that South Carolina's forfeiture practice violate both the U.S. Constitution and the state's because the statutes "(1) place the burden on the property owner to prove their innocence, (2) unconstitutionally institutionally incentivizes forfeiture officials to prosecute forfeiture actions, and (3) do not mandate judicial review or judicial authorization prior to or subsequent to the seizure." He also notes that the statutes violate citizens' Eighth Amendment protections against excessive fines.

South Carolina's asset forfeiture system is particularly terrible because 75 percent of the seized assets go directly to the law enforcement agency that seized the property, while 20 percent goes to the state solicitor's offices (the prosecutors). The money seized goes directly to the people trying to seize it. The money seized is supposed to be used solely for "drug enforcement activities," but John observes that this restriction has very little oversight; law enforcement ends up approving spending above and beyond what their agencies have budgeted, with the understanding that they'll make up the difference from seizures. That doesn't even get into the issue that tying a police department's budget to proceeds from fighting the drug war warps their priorities to such a degree that they're not focusing on crimes that have actual victims.

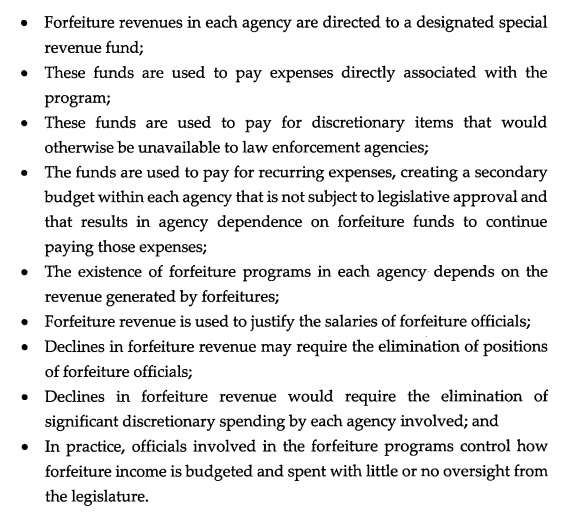

Later in the ruling, John painstakingly goes through a checklist to show exactly how the state's forfeiture system leads to bad incentives and a cycle of revenue-seeking:

"We have to find more money to seize or our budget will run out and we'll lose our jobs," is not a model for a policing system that is focused on fighting actual crime.

But the fight to reform South Carolina's system is far from over. The decision doesn't extend statewide, and Horry County's Solicitor's Office has filed a motion asking John to reconsider his ruling, noting that, among other things, the defendant in this case pleaded guilty to the crimes and the seized cash is worth much less than the potential maximum fine of $50,000 he could have faced.

Writing at Forbes, Nick Sibilla notes that in the wake of local reporting about the expansive abuse of asset forfeiture in South Carolina, lawmakers attempted to pass a bill which would have eliminated civil forfeiture entirely. It stalled due to some technical issues with the wording, but Sibilla expects a revised version to return in the next legislative session. If it passes, South Carolina would join New Mexico, Nebraska, and North Carolina in completely eliminating civil asset forfeiture. A conviction would be required in order for police and prosecutors to try to keep somebody's cash and property for themselves.

Read John's ruling here.

Show Comments (69)