SCOTUS Debates Whether the Right to Trial by Jury Should Mean the Same Thing in State and Federal Court

Understanding what’s at stake in Ramos v. Louisiana.

The Sixth Amendment says that "in all criminal prosecutions, the accused shall enjoy the right to a speedy and public trial, by an impartial jury." This week, the Supreme Court heard oral arguments in a case that asks whether that constitutional provision should be allowed to mean one thing in federal court and something else in state court.

At issue in Ramos v. Louisiana is an aspect of criminal procedure known as the unanimous jury rule. According to a long line of Supreme Court cases, the Sixth Amendment requires a unanimous jury verdict before an individual may be convicted of a crime in federal court. At the same time, however, in Apodaca v. Oregon (1972), the Supreme Court held that state criminal convictions do not require a unanimous jury. Ramos v. Louisiana centers on whether this two-track approach is constitutional when it comes to criminal juries.

Evangelisto Ramos was convicted of second-degree murder in 2015 by the 10-2 vote of a Louisiana jury. Had a federal jury failed to reach a unanimous verdict in his case, Ramos never would have been convicted. At the Supreme Court this week, Ramos' lawyer, Jeffrey Fisher, told the justices that "what we're asking you today to do are to reaffirm two things the Court has said many, many times over the years. One is the Sixth Amendment requires unanimous verdict. And, second, when an incorporated provision applies to the states, it applies the same way as it does to the federal government."

Fisher's reference to incorporation was a reference to the 14th Amendment, which, among other things, forbids the states from violating fundamental individual rights. For over a century, the Supreme Court has invoked the 14th Amendment as a means of incorporating, or applying, the various provisions contained in the Bill of Rights against the states. In fact, the Court did so just last term. In Timbs v. Indiana (2019), the justices held that the Eighth Amendment's ban on the imposition of "excessive fines" applies equally against the federal government and the states. "If a Bill of Rights protection is incorporated," the Court said in Timbs, "there is no daylight between the federal and state conduct it prohibits or requires."

That's the approach that Ramos and his legal team want to see adopted when it comes to the Sixth Amendment's unanimous jury rule.

Judging by the oral arguments, at least some members of the Court seem potentially inclined to decide the case that way.

"We have 32,000 people that are currently serving time for serious crimes," Louisiana's Solicitor General Elizabeth Murrill told the justices. "Each of these convictions would be subject to challenge if Apodaca is reversed" and the non-unanimous criminal jury system for the states is declared unconstitutional.

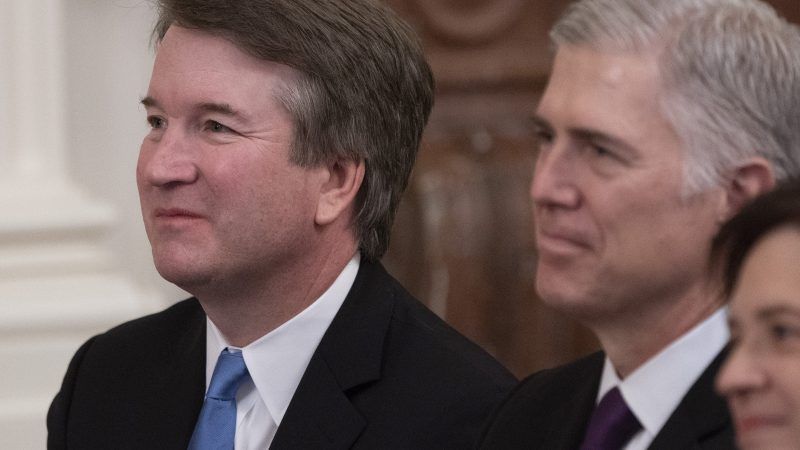

"Counsel, on your reliance interests," Justice Neil Gorsuch observed a few minutes later, "you say we should worry about the 32,000 people imprisoned. One might wonder whether we should worry about their interests under the Sixth Amendment as well." How much weight, Gorsuch asked, should the Court give to "a single state's claim of reliance with respect to a subset of criminal convictions, when we're talking about a Constitution that's supposed to endure?"

Justice Brett Kavanaugh struck a similar note a few minutes after that. "Assume the Sixth Amendment requires unanimity. I know you disagree," he told Murrill. "It seems to me there are two practical arguments for overruling Apodaca," Kavanaugh continued. "One is, as Justice Gorsuch says, there are defendants who have been convicted and sentenced to life, 10-2 or 11-1, who otherwise would not have been convicted. So that seems like a serious issue for us to think about in terms of overruling."

The other argument, Kavanaugh said, is that Louisiana's non-unanimous jury approach "is rooted in a—in racism, you know, rooted in a desire, apparently, to diminish the voices of black jurors in the late 1890s." Don't those two arguments, Kavanaugh asked the state's solicitor general, seem to cut against your case?

Other members of the Court, however, seemed potentially less inclined to overturn the precedent allowing for non-unanimous criminal juries in the states. "It is certainly true that we, in recent years, have rejected the two-track idea about incorporation, but the opposite isn't a crazy idea," Justice Samuel Alito told Murrill. "It's a respectable argument…. It hasn't won the day completely, but that's what Apodaca rests on."

"Well, Justice Alito," Murrill replied, "if you're telling me that there is a little bit of daylight, then I'll take it."

A decision in Ramos v. Louisiana is expected by June 2020.

Editor's Note: As of February 29, 2024, commenting privileges on reason.com posts are limited to Reason Plus subscribers. Past commenters are grandfathered in for a temporary period. Subscribe here to preserve your ability to comment. Your Reason Plus subscription also gives you an ad-free version of reason.com, along with full access to the digital edition and archives of Reason magazine. We request that comments be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment and ban commenters for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

I tend to like the new blood on the Court. Arbitrary precedents seem arbitrary.

Really curious to see how each of the Justices rules on this one. This will tell us a lot about each of them.

Wait a minute. What is this constitution thing they keep talking about?

Is there something other than the socialist's power grab we are supposed to care about?

Wouldn't it be nice if you guys could worry about things that were actually happening on the real planet earth?

love it. 10-2 life sentences are wrong.

Everything from Louisiana is automatically suspect.

tabasco never disappoints but yes.

Louisiana Hot Sauce is better but yeah.

"Everything from Louisiana is automatically suspect."

Except that Louisiana changed their rule last year. Currently Oregon is the only state that allows non-unanimous juries.

I was a registered voter in Oregon for 27 years. Never received a single summons to jury duty. I didn't even know this was a thing. Now I am kinda glad I never got summoned, because my vote to nullify some stupid regulation would have been ignored anyway.

Sadly, even if it wasn't, it would likely just end in a hung jury and the prosecutor trying the poor bastard again.

I wonder if Kavanaugh's recent run in with arbitrary and malicious charges has soften his deference to the state? I was worried he would be another Alito but his agreeing with Gorsuch in at least oral arguments gives me hope.

Nope. Everyone knows that judges leave their personal lives and opinions outside the courtroom. That's what makes them so just and consistent. And robotic.

Even the wise empathetic ones?

The 14th Amendment guarantees the states provide due process of law. The incorporation doctrine says that all of the rights in the BOL necessary for due process are therefore incorporated as rights under the 14th Amendment.

The founders put the right to a unanimous jury verdict in the BOL. Why would they have done that if they didn't view it as essential to protecting due process of law?

I don't see how the incorporation doctrine means anything if it doesn't incorporate one of the rights listed in the BOL that specifically applies to criminal trials.

And for the record, I think the same logic applies to grand juries and the courts are wrong in not incorporating that right as well.

one of the historical justices argued the entire bill of rights should be incorporated ... Hugo Black maybe ... i agree

I think that would be good result but I don't think that is what the 14th Amendment actually means or was intended to mean. So, I wouldn't go for that.

I think it was, in fact, exactly what the 14th amendment actually means, and was intended to mean. And how it was interpreted until the Court set out to render ratification of the 14th amendment moot.

Partial incorporation is a consequence of the Court being reluctant to overturn the Slaughterhouse cases in one fell swoop, as they should have. They STILL haven't admitted they were bad rulings, which is why we've got this silly "substantive due process" workaround.

I think if it was meant to mean that, they would have said so in so many words. If they mean that, then why doesn't the amendment say "all federal rights are also state rights"? It doesn't say that.

And the slaughter house cases are different than incorporation. The Slaughter House cases are privileges and immunity and relate to the states' duty to respect rights granted by other states. You could have decided those cases differently and still said that federal rights are only available to the extent necessary for the due process of law. You get every state right any state grants you. You get only the federal rights necessary for due process.

Alas, it's been 30 years since I turned in my law school seminar paper and I no longer have the citations, so apologies in advance. There were two political factions who had recurring open debate as to what the 14th Amendment was to accomplish. One senator(?) orated that the "privileges and immunities" referenced in the 14th referred to listed in the original 10 amendments. Others were not in favor of such infringement on the rights of the states. The drafters left the terms undefined, though AT THE TIME the proponents of incorporation had reason to believe that the Supreme Court would, in fact, favor and deliver incorporation of the Bill of Rights under the P&I phrase. Oopsies!

I enjoy these sorts of threads because Jeff, Shreek and the other leftist troll franchises never show up. They only show up if there are partisan Democratic points to be made, which there are not on these kinds of threads. Without them you can actually have an intelligent discussion about something.

I'm here dipshit and I like what you wrote.

re: "The founders put the right to a unanimous jury verdict in the BOL."

Not exactly.

Unanimous juries for criminal trials were part of established common law at the time of the Founding. See, for example, Blackstone, Commentaries *378–79. And many of the Founders did speak near the time of the passage of the 6th Amendment of their understanding that juries were to be unanimous (John Adams in 1797 and Justice James Wilson in 1804, for example. But it was not officially codified as a requirement for federal trials until United States v. Burr in 1807. Unanimity is not actually in the text of the Sixth Amendment.

Note also that that the current case is only about the requirement in the context of felony criminal trials. As far as I know, no one in this case has discussed changing those states that allow non-unanimous misdemeanor trials (AZ and NY, I think) nor changing any of the many scenarios both federal and state where non-unanimous civil trial decisions are allowed.

I don't understand what this whole "incorporation" crap comes from, even if it relies on the odious 14th amendment.

Article 6, of the original Constitution, clearly states: This Constitution, and the Laws of the United States which shall be made in Pursuance thereof; and all Treaties made, or which shall be made, under the Authority of the United States, shall be the supreme Law of the Land; and the Judges in every State shall be bound thereby, any Thing in the Constitution or Laws of any State to the Contrary notwithstanding.

Why is this article ignored?

It doesn't say only federal judges shall be bound by it. It says "the Judges" and that "any Thing in the Constitution or Laws of any State to the Contrary notwithstanding."

That's pretty clear to me that this included all of the amendments, too.

But wait. Aren't Gorsuch and Kavanaugh the racists on the Court? Why would they be doing anything but supporting Louisiana to the hilt? Could it be that the Democrats' interpretation of them is questionable?

Good troll attempt. Libertarian decisions are made once in a while by both conservative and liberal jurists

Not only is this a good opportunity to give the Constitution a robust (and quite legitimate) interpretation by requiring the states to have unanimous juries - this is a classic case of "minorities hardest hit."

After all the blood, toil tears and sweat expended to prohibit racial discrimination in the selection of jurors, can the states just shrug it off and say, "up yours, our white jurors will simply outvote any minority jurors."

I understand that Louisiana voters have required jury unanimity for *future* cases, so the question is (a) what happens to the people who got imprisoned on divided verdicts before the voters woke up, and (b) what happens in Oregon, the only other state that I know of with a non-unanimity rule.

As for Oregon's motivations, I don't know, it may have been more of a misplaced faith "law 'n order" - some crimes are so serious that reasonable doubt shouldn't be a defense.

It would be easier for the Supreme Court to abolish a rule which mainly exists in Oregon and (vestigially) in Louisiana, than to do something really momentous like requiring 12-person juries or grand jury indictments for serious crimes.

To answer your questions, Supreme Court rulings on procedure like this only apply in the future. So, I do not thing that the people who have been convicted by non unanimous verdicts will be able to have their convictions overturned since their convictions were legal under the law of the time. To give an other example, no one who had been convicted based on a confession given without receiving notice of their rights before the Miranda decision was able to get their convictions overturned. The rule only applied going forward.

As to your second question, the Oregon law will be invalid under the new decision and any conviction based on a non unanimous verdict will be subject to being overturned on appeal or in federal court on a habeaus petition.

It seems this Louisiana guy appealed before the voters got wise, but his appeal remained pending afterward, so the Supreme Court can still step in.

Of course it's harder when your conviction is final, even if later cases indicate your conviction may not have been legal.

To answer your questions, Supreme Court rulings on procedure like this only apply in the future. So, I do not thing that the people who have been convicted by non unanimous verdicts will be able to have their convictions overturned since their convictions were legal under the law of the time. To give an other example, no one who had been convicted based on a confession given without receiving notice of their rights before the Miranda decision was able to get their convictions overturned. The rule only applied going forward.

As to your second question, the Oregon law will be invalid under the new decision and any conviction based on a non unanimous verdict will be subject to being overturned on appeal or in federal court on a habeaus petition.

Reminds me of when the Bushpig AG Alberto Gonzalez said “There is no expressed grant of habeas in the Constitution"

That is not what he said retard. He said there is not one regarding prisoners or war or those detained under the laws of war.

Go away and stop posting on a thread you know nothing about.

No, he was talking about rights in general.

The fact that the Constitution — again, there is no express grant of habeas in the Constitution. There is a prohibition against taking it away.

That is a direct quote from Senate testimony.

And in context of what he is talking about, he is saying that no such right exists for people captured under the laws of war.

You are too stupid to understand any of this. Just go the fuck away. You wasting everyone's time.

GOP John. Defending all things Republican since the Bushpig years.

There isn't an explicit grant of Habeus in the constitution. What there is is the existing right under common law which the document prohibits the federal government from depriving its citizens. That means you can't use the Constitution to create a right of habeus that doesn't otherwise exist.

Not everything is partisan you drooling moron. The law and the Constitution say what they say.

Now say thank you for your law lesson and go away.

Fuck off, slaver.

This sort of case is one reason we need judges with actual experience in state-level courts on the Supreme Court. AFAIK, every judge on the court now has a virtually identical career path - go to Ivy and be taught by 3-5 conlaw professors, go to DC and piss around doing nothing worthwhile, get appointed to appellate federal court, get promoted to Supreme Court. The last two to have state-level experience were Souter and O'Connor - which means it has been 30 years since a judge with that experience has even gone through the Senate confirmation process.

I'm perfectly fine with incorporating federal amendments - but I don't trust the skills/capability of judges to judge that if they have never conducted a trial. Same with judges who have legislative experience and who understand the sausage making process. Same with judges who may have some actual fucking specific knowledge beyond political reliability re abortion - like intellectual property or civil rights/liberties of the individual or technological impositions on rights or economics to know when market can handle an issue and when markets can't to judge when legislation itself can become an overbroad imposition.

Sotomayor was a federal district judge in New York. And her performance as a judge is further evidence for your point. She has been very good on criminal procedure issues.

Fair analysis, but you add

"The last two to have state-level experience were Souter and O’Connor"

and I don't necessarily see them as all that great, thought at least O'Connor had some insights on federalism which someone without state experience may have lacked.

Whether they get plucked from the ranks of the state judiciary or from academia, I'd say one key qualification would be the ability to say "no" to lawless arguments and explain why these arguments are wrong - since there's a strong movement to have the courts perpetrate lawlessness in the name of law. Scalia was one of the non-state-experience-having judges, and he could sometimes be off base (eg. Raich), but when it came to eloquently denouncing many of the worst schemes of the lawlessness-by-law crowd, he was inspirational.

As for experience with abortion, I'd be more general and say experience as a parent, even - even if they didn't happen to abort their kids then they still have relevant experience to the abortion debate, in my mind.

I don’t necessarily see them as all that great,

I'm not proposing that as a way to get 'great' judges. And I suspect you are not really judging 'great' either but merely partisan/reliable. I'm proposing it as a way to get different knowledge/skills/experiences on the court. With the assumption that truly different experiences are what lead to more informed discussions among the judges which can then lead to better more thoughtful maybe even creative decisions. At core, that 'great decisions' don't emanate from 'great judges' as individuals but from a court that can actually better inform itself about all the conflicting perspectives/context of a case.

As for experience with abortion,

My opinion is that that issue has become a curse. Prez's are appointing almost solely on that issue. The Senate no longer seems to give a shit about anything else. Elections are now marketed on trying to ensure reliability on that issue re all judicial nominations. People actually want judges to live longer or die sooner based solely on that. It has completely diminished what a judiciary should be and what the SC needs to be in the 99% of cases that don't involve abortion.

That said - I don't per se oppose ideological judges with an overarching legal philosophy which they apply to every case. That skill is also necessary on a SC - but it is merely ONE skill. Akin really to what a law school professor might bring to the court.

In 1950, the SC received petitions for 1200 cases. In 1975, the SC received petitions for 3940 cases. Now the SC receives petitions for 8000 cases per year.

I suspect a court of nine will never be able to hear more than 60 cases under plenary review (argued before court) and 100 not under plenary review and less than a handful under original jurisdiction. But that limit also means it is more important now than ever for SC judges to have a broader experience beyond an overarching legal philosophy.

"more important now than ever for SC judges to have a broader experience beyond an overarching legal philosophy."

Which is why I agreed with the fairness of your analysis.

"I suspect you are not really judging ‘great’ either but merely partisan/reliable....I don’t per se oppose ideological judges with an overarching legal philosophy which they apply to every case. That skill is also necessary on a SC – but it is merely ONE skill."

And...you just got close to my position without knowing it, thus taking upon yourself some of the insults you applied to me.

If this skill is "necessary," then of course we ought to do not more than "not per se oppose it," we need to affirm it as a minimum qualification, which your words seem to do. As to the position that that's the *only* requirement, yeah I certainly join you in denouncing anyone who holds that position. Because as between two candidates who meet the minimum qualification of having a proper philosophy, we should choose the candidate who is more learned and experienced.

Re abortion - I seem to have misunderstood your comment as calling for candidates to have experience with the abortion issue. I'm sorry for missing your point.

Abortion "has completely diminished what a judiciary should be and what the SC needs to be in the 99% of cases that don’t involve abortion."

If a dead canary is a sign of the presence of toxic fumes and the need to get out of the mine, an aborted baby is a sign of the presence of a toxic philosophy and the need to escape to a different philosophy.

You seem to agree the skill in applying an overarching philosophy is "necessary" - I'd only clarify that having a *good* philosophy which opposes lawlessness in the name of law should be part of that skill.

Is the federal unanimous jury rule solely derived from SCOTUS precedent referring to English common law? Since it does not seem to appear in the actual text.

What I have found suggests that the federal standard 12 member jury standard is derived from early research on English Common Law by the Court that has since proved debatable. Also, as I recall, Louisiana's law code uniquely derives from the Napoleonic Code rather than Common Law.

The Oregon case referenced in the article ruled that the 6th Amendment right to an impartial jury meant the right to an unanimous verdict. The problem was that it was a plurality opinion. Four of the justices rejected the right to a unanimous verdict altogether. Four other justices found that there was a right to a unanimous verdict in the 6th Amendent and that the right was incorporated into the 14th and thus applicable to the states. Justice Powell somehow convinced himself that the 6th Amendment granted a right to a unanimous verdict in federal courts but that this right somehow was not essential to due process of law and thus was not incorporated by the 14th Amendment and thus not applicable to state court trials.

So really only one judge ever thought that there was a right to a unanimous verdict in federal court but not state court. Of all the possible positions, that seems to be the weakest and least consistent.

OK, but my question was where does the sixth amendment require unanimity, as it does not explicitly appear in the text. Is it based on an understanding that common law required unanimous decisions and so is baked into the definition of "trial by jury"?

I am trying to understand where this argument is derived from.

That is a great question. I cannot find Powell's opinion on line. The dissenting opinion is one paragraph that refers to Powell's conclusion that it is covered by the 6th Amendment and then says it is applicable to the states. I would love to read his concurrence but it is not online for some reason.

Yeah it's just something passed down from English common law. Looking at a few cases going back to the 1890's they just seem to take it as a given that common law required unanimity.

First thing I've liked about Kavanaugh. Good for Gorsuch who is always right.

Looking forward to seeing them make the right final decision.

And as usual, Alito is a total douche.

I'm gonna guess that Gorsuch, Kavanaugh, and Sotomayer will be definite votes for the 6th applying to states (Sotomayer tends to be good when it comes to criminal justice, regardless of how she votes on other things). Not sure how the rest will handle it, you'd think that the Big Gov types like Roberts would also support it because it forces states to step in line with the fed, but who knows.

I have read the 6th Amendment a LOT, I don't recall it ever mentioning that the Jury has to come to a unanimous decision as Mr Root is claiming in the article.

"That's the approach that Ramos and his legal team want to see adopted when it comes to the Sixth Amendment's unanimous jury rule."

If there's no unanimity requirement or numerical limit (which isn't mentioned in the Sixth Amendment either), what's to stop us from adopting the Athenian jury system of bringing in a large assembly of citizens to decide guilty and punishment by majority vote?

Kidney donors are needed at hope hospital from all blood group for $80,000.00/-indian rupees contact us now call or whatsap for more information +918970196553.

Bold strategy, Cotton. Let's see if it pays off.

Well, that's straight up illegal. Flagaroonie.

Kidney donors are urgenlty needed for a good amount of money contacct us for more details +918970196553

"Kidney donors are urgenlty needed for a good amount of money"

Why do you want money from kidney donors? I'm sure you can find a source of income from other people.

The Soviet Supreme Court of the Union of Socialist Slave States needs to make a statement here.

It needs to make it very clear the police, not some robed asshole will make the decisions of who and what is right and wrong.

This way we can finally rid our wonderful socialist state of the needless, useless and outdated idea of due process, trial by jury and trials by our peers.

Such bourgeois beliefs need to placed in the rightful place of the dustbin of history where it belongs.

We need to trust our obvious betters, the Thought Police and the brutal, sadistic but well-meaning cops that look out for our socialist needs on a daily basis. That means they need leeway in making decisions to do what is necessary to ensure our socialist slave state stays in tact and never wavers from its guarantee of being an oppressive police state.

Only then will we be able to enjoy all the fruits of a socialist society.

Thanks admin for giving such valuable information through your article . Your article is much more similar to https://www.creative-diagnostics.com/WHSC1-Knockout-Cell-Lysate-256647-513.htm word unscramble tool because it also provides a lot of knowledge of vocabulary new words with its meanings.