Michigan Health Care Regulators Just Restricted Access to Promising New Cancer Treatments

The state's largest hospital chain didn't want the competition.

A state commission, acting at the behest of Michigan's largest hospital chain, voted on Thursday to restrict cancer patients' access to promising, potentially lifesaving treatments.

It's another example of the problems caused by little-known state-level health care regulations known as Certificate of Necessity (or, in some states, Certificate of Public Need) laws. These laws are supposed to slow down increasing costs, but they often end up being used to restrict competition, often at the request of powerful hospital chains.

That's exactly what seems to have happened in Michigan, where the state's Certificate of Need Commission voted Thursday to impose new accreditation requirements for health care providers who want to offer new immunotherapy cancer treatments. Those treatments attempt to program the body's own immune system to attack and kill cancer cells, and they have become an increasingly attractive way to combat cancer alongside more traditional methods, such as surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation.

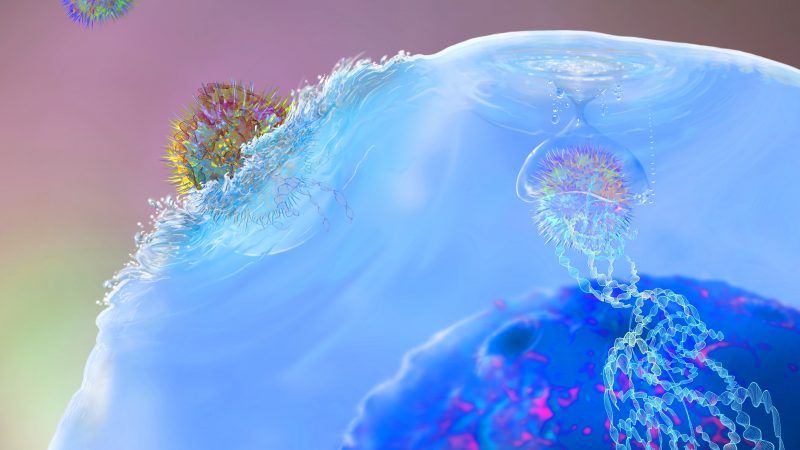

One particularly promising type of immunotherapy involves literally bio-engineering T-cells—the foot-soldiers of the body's immune system—and equipping them with new Chimeric Antigen Receptors that target cancer cells. This so-called "CAR T-cell therapy" is every bit as badass as it sounds:

But under the new rules adopted by the Michigan Certificate of Need Commission, hospitals will need to go through unnecessary third-party accreditation processes before being able to offer CAR T-cell therapies. Even after obtaining that additional accreditation, hospitals would have to come back to the CON commission for another approval—a process that effectively means only large, wealthy, hospital-based cancer centers will be able to offer the treatments.

The new rules were "opposed by cancer research organizations, patient advocates and pharmaceutical companies, who argue it would add an unnecessary level of regulation and deny many patients access to potentially life-saving treatment," reports Michigan Capital Confidential, a nonprofit journalism outfit covering Michigan politics.

In favor of the new rules? The University of Michigan Health System, the state's largest hospital system, which argues that the new rules are necessary for patient safety.

To be clear: It's not a question of patient safety. In 2017, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved two CAR T-cell therapies for children suffering from leukemia and for adults with advanced lymphoma. Although the technology is still being developed and other uses of T-cell therapies are yet to be approved by the FDA, the Michigan CON Commission does not do medical testing. Like similar agencies in other states, the extent of its mandate is purely economic, not medical.

Anna Parsons, a policy coordinator with the American Legislative Exchange Council, points out that the safe administration of CAR T-cell therapy does not require hospitals to make new capital investments—which is the only time CON laws should apply. Literally any FDA-certified hospital should be capable of offering these treatments, since all the high-tech bioengineering is done at other locations. The only thing that happens at the hospital is a simple blood transfusion.

Though the specific applications of CON laws differ from state to state, their stated purpose is to prevent overinvestment and keep hospitals from having to charge higher prices to make up for unnecessary outlays of capital costs. But in practice, they mean hospitals must get a state agency's permission before offering new services or installing new medical technology. Depending on the state, everything from the number of hospital beds to the installation of a new MRI machine could be subject to CON review.

As part of that review process, it's not uncommon for large hospital chains to wield CON laws in order to limit competition, even at the expense of patient outcomes.

From 2010 to 2013, for example, the state agency in charge of Virginia's CON laws repeatedly blocked attempts by a small hospital in Salem, Virginia, to build a neonatal intensive care unit (NICU), in large part because a nearby hospital—which happened to have the only NICU in southwestern Virginia—objected to the new competition. Even after a premature infant died at the Salem hospital, state regulators continued to side with the Salem hospital's chief competitor, against the wishes of doctors, hospital administrators, public officials, and patients who repeatedly testified in favor of letting the new NICU be built.

Even when the outcomes aren't as tragic as dead babies or untreated cancer patients, CON laws have adverse consequences. In 2016, reseachers at the Mercatus Center at George Mason University found that hospitals in states with CON laws have higher mortality rates than hospitals in non-CON states. The average 30-day mortality rate for patients with pneumonia, heart failure, and heart attacks in states with CON laws is between 2.5 percent and 5 percent higher even after demographic factors are taken out of the equation.

When it comes to CAR T-cell therapy, there does not seem to be any compelling reason for Michigan regulators to use CON laws except to explicitly limit which hospitals can provide those treatments.

"We will never know how many more lives this therapy could have saved if the added time and expense these onerous regulations put in place discourage hospitals and clinics from providing treatment in the first place," Parsons wrote this week in The Detroit News.

Under Michigan law, the legislature has 45 days to review and overturn the decisions of the CON Commission. Here is one situation where that is exactly what it should do.

Show Comments (43)